Since 1973, hip-hop has been a megaphone for Black men. The mental health struggles, sexual awakenings, and aging revelations have been shared worldwide in its lyrics and advocacy. To celebrate hip-hop’s 50th anniversary and Black History Month, Men’s Health is exploring the culture’s past five decades by highlighting the moments and movements that reflected and influenced Black men’s health. To read the rest of the stories, click here.

IT’S OCTOBER 5, 1995, and the palatial halls of Madison Square Garden are shivering from the cheers of young people being treated to performances from their favorite rappers…and lessons about sex. In between the Notorious B.I.G.’s proclamations of his love for women calling him “Big Poppa” and Wu-Tang Clan explaining why cash rules everything around them, video testimonials from people with HIV/AIDS were depicted on screen. T-shirts and refreshments were passed out, and so were condoms. This wasn’t just a rap concert; it was hip-hop finally getting serious about sex.

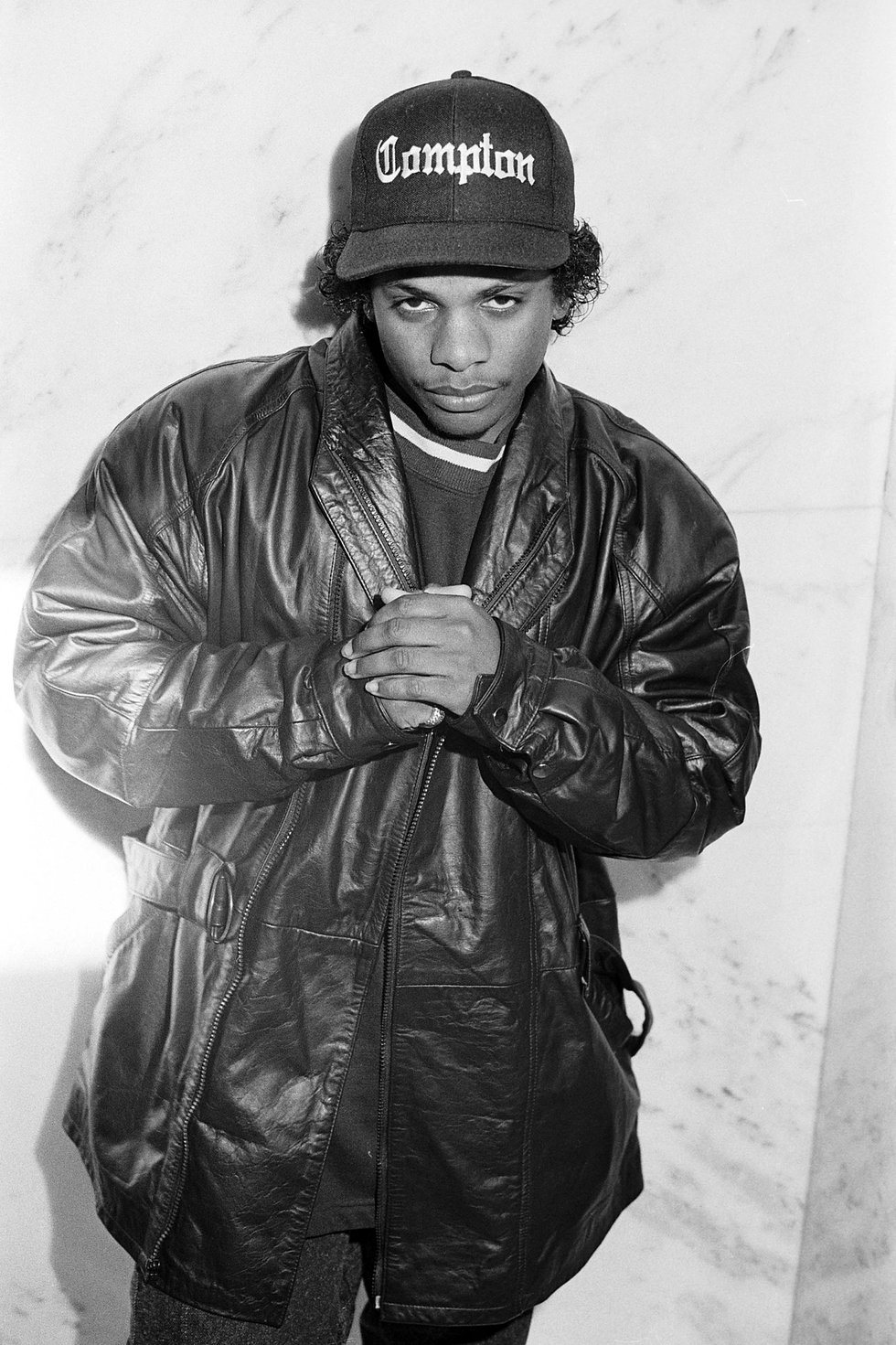

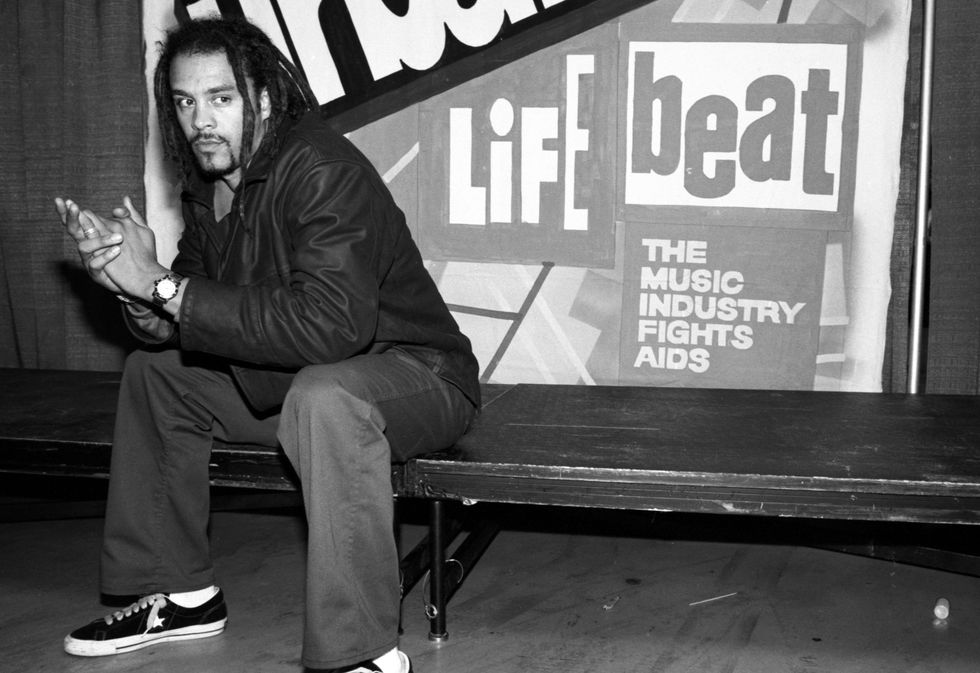

That all took place at Urban Aid 4 Lifebeat, a five-hour benefit concert that would’ve likely never taken place if west coast gangster rap pioneer Eric “Eazy-E” Wright hadn’t died at 31 from AIDS complications weeks after he became the first major rapper to publicize his condition. According to Fred T. Jackson, an Elektra Records project manager at the time who worked at the concert, Eazy-E’s death forced hip-hop and its fans to change the way they viewed HIV/AIDS.

In the 1990s, Jackson remembers having to hide his homosexuality in an industry that laughed off HIV as “the gay disease”—a view that isn’t just homophobic, but scientifically untrue, as anyone can contract HIV, regardless of gender, sex, or sexual orientation. Meanwhile, the epidemic was ripping Black men he loved from his life—and not enough people were talking about it.

“Two of my friends that were truly my brothers both passed. They were living through it quietly in some way, not even sharing their status with me,” Jackson tells Men’s Health. “I still, to this day, never got to ask why they didn’t share it with me. It was scary during the ‘90s. We didn’t know why our friends were dying.”

Yearning to educate the people in his beloved industry and the Black men who followed it, Jackson went on to play a role in what industry insiders remember as hip-hop’s first unified HIV/AIDS awareness initiative. Here, we talk to Jackson about how America’s homophobic views of HIV/AIDS shaped hip-hop, how he navigated the music business as a Black gay man, and how hip-hop getting serious about sex in the ‘90s put other Black men in action to do the same for years to come.

Men’s Health: You worked at Elektra Records as a project manager from 1988-1995. How did your sexual orientation affect how you maneuvered through the hip-hop music industry?

Fred T. Jackson: It wasn’t easy. I felt I had to find a path. Many times I felt this [homophobia] wasn’t happening to anyone else but me, even though I knew it was happening to others and people were sort of walking through it in their own way. I compartmentalized and told myself to just focus on work. I was honored and excited to be a part of the entertainment industry. I had to navigate my way through this. Then there was my personal life, and I could be a little bit freer and a little bit more comfortable in my skin and who I am. I came from a family based on faith. But, I was still trying to be sure to remain myself.

What about hip-hop during the ‘90s made you and others feel like you couldn’t fully express your sexual identities?

Hip-hop was still growing. It was getting into its 20s. Almost like a person itself, it was figuring out who it was and what its voice was, what it wanted to stand for, and what it was open to. At the time, hip-hop was not in a place of acceptance. As hip-hop found itself beyond its neighborhoods and streets, learning about different cultures, seeing different people, and seeing the world, I think there became a realization that there are a lot of people out there living a lot of different lives. It grew up. For some, they were pretty set in their way of thinking and point of view and weren’t necessarily open to different lifestyles.

This content is imported from youTube. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

One of those mentalities hip-hop stuck to early on was brushing off HIV/AIDS as the “gay disease.” From your perspective, was that how other Black men viewed it?

It was not just Black men. Almost the entire world was saying the same. It was a narrative that, unfortunately, was happening from the White House, our churches, and everywhere. That was what was being said and shared. How could we expect the hip-hop community and the Black community to say differently when that’s all that was being presented in the press, in the media, from the pulpits and from the White House correspondent desk?

In your experience, how did the Black community treat gay Black men?

You already had members of the Black community who weren’t open to gay Black men within their community. Firstly, there’s the close-minded worry of having their family associated with a gay man because he could turn their children gay or try to push up on their husbands. Secondly, there was the fear of gay Black men infecting them. That amplified things even more because now there’s this view of it as a gay man’s disease.

What were your first-hand experiences with the impact of HIV/AIDS? Did you lose any friends to HIV/AIDS during the ‘90s?

One of the stories that will always stay with me is when I knew this crew of friends that were Black men. I remember even dating one of them one or two times. Within the course of the year, they were all gone. They had all passed. That was probably in the mid-’90s or so. An even closer encounter to me was when two of my friends that were truly my brothers both passed. They were living through it quietly in some way, not even sharing their status with me. I still, to this day, never got to ask why they didn’t share it with me. It was scary during the ’90s. We didn’t know why our friends were dying. Or, the available drugs were not affordable or not accessible.

On March 27 1995, Eazy-E died from AIDS complications. Since you were working in the music industry at the time, can you tell me how the conversation around HIV/AIDS changed when he died?

It brought up questions people had to grapple with—and not just go into rumor about, but really ask themselves, “What happened here? If it can happen to this person, who’s to say it can’t happen to every artist on all of our rosters?” We wanted to figure out what support we could build to ensure this does not overwhelm our industry as we saw with other entertainment industries. After the initial shock [of Eazy-E’s death], the sentiment was, “It’s time to share what we know.”

Seven months after Eazy’s death, hip-hop held its first benefit concert for HIV/AIDS awareness—UrbanAId’s Lifebeat concert. How did Eazy’s death inspire hip-hop to get more involved in that manner?

We had heads of our industry sitting in their offices asking those two questions: Was he gay? Was he a drug user? If they are not equipped with the basic information, how were we going to expect a young boy in Brooklyn to have the facts? How are we going to think he has the facts if this EVP of urban promotion at a major record label doesn’t have facts? We realized we had work to do to educate. We had to find a way to use our outlet, our voices in this industry, to educate. When LifeBeat came about, they looked to the record labels for volunteers to help with everything from mailings to relationships with artists or any resources that could be helpful. I was excited to support however I could.

How soon after his death do you remember hearing about UrbanAid?

I started with LifeBeat as a project manager in May 1995. I want to say maybe by April is when I heard LifeBeat was planning a big initiative to speak to the urban community.

What do you remember about the concert?

We were utilizing all the tools we had within the industry to tell them publications, “You have to stop what you’re doing as far as just promoting the music and entertainment, and use your outlets to promote the message of safe sex and self-care to the urban community.” One of the performers, Salt-N-Pepa, had a song out at the time called “Let’s Talk About Sex.” It was empowering, honest, and presented an opportunity for a real conversation to be had. They graciously did a PSA to focus on the initiative and to bring yet another narrative saying proudly, “Let’s talk about HIV and AIDS.”

This content is imported from youTube. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

I recall [male R&B group] Jodeci went by Stand up Harlem [housing for single adults living with HIV/AIDS] and saw the work they were doing. We brought the media and the Jodeci fans there to raise awareness about what Stand Up Harlem does. They had conversations with directors and coordinators and spoke with young Black men benefiting from the services they offer. I remember Bone Thugs N Harmony did a message speaking on the passing of Eazy-E and how much they loved him.

We had over a hundred volunteers helping [at the benefit concert]. We had tables set up everywhere Madison Square Garden would let us. We were giving out condoms, giving out literature, answering questions, and doing whatever we could to touch every person who came there that night. We didn’t want people to just have a great show, we wanted them to really feel as though they walked out of that venue with a better understanding of HIV/AIDS and the resources available to them.

Did you see any direct impact on the lives of Black men from this concert?

One of the greatest ways we saw it was the influx of volunteers. After we did the concert, and it got its fair share of press, we saw this increased growth in people reaching out to LifeBeat asking to be volunteers so they could help. Whether they wanted to man a booth or they were part of the culture and industry and wanted to do whatever they could. We made sure when promoting the concert that we let outlets and people know HIV and AIDS don’t end with Eazy-E. For every Eazy-E, there are thousands of other young Black men who are living with HIV or AIDS, or don’t even know because they’re not being tested. We didn’t want to talk softly about it. This was an epidemic.

How do you feel hip-hop changed after UrbanAid?

I think many realized they couldn’t say they were a voice of the community without realizing that HIV and AIDS are hurting the community. Many of them may not have said it, but you have to believe many of them dealt silently or privately with the loss of friends and family. Or they dealt with friends and family who were living with HIV and AIDS. It was another reminder that they have a voice and a responsibility to utilize their voices in a constructive way that serves the community.

Keith Nelson is a writer by fate and journalist by passion, who has connected dots to form the bigger picture for Men’s Health, Vibe Magazine, LEVEL MAG, REVOLT TV, Complex, Grammys.com, Red Bull, Okayplayer, and Mic, to name a few.

Comments are closed.