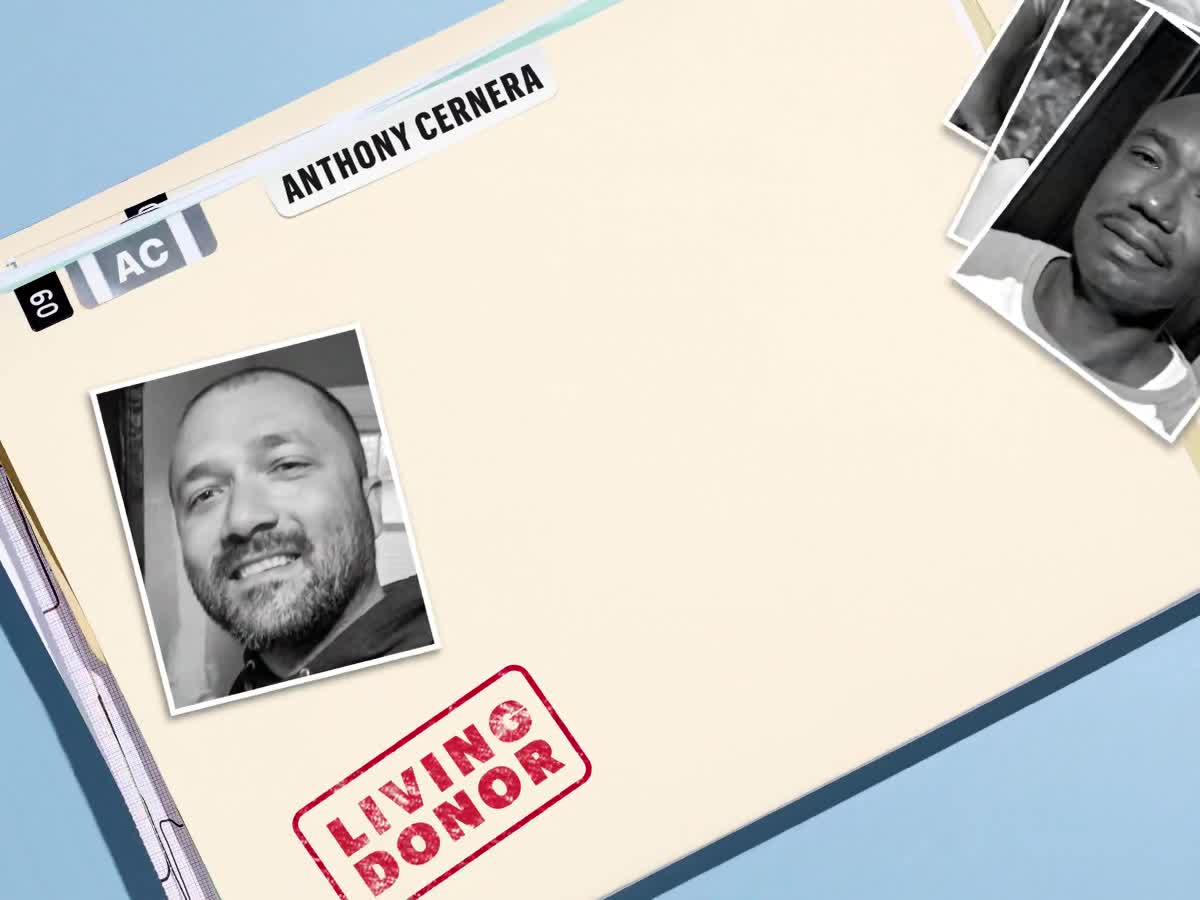

AS HE MEDITATES, he’s fixated on his kidneys. Eyes half closed, legs crossed in lotus position. It’s a little after dawn one fall day in 2015, and Anthony Cernera sits on a thin mat inside his sparsely furnished apartment on Long Island, New York, looking inward—perhaps a bit too inward.

He has two of them, the kidneys. That’s two fist-sized, bean-shaped organs capable of continuously filtering waste and extra fluid out of his bloodstream. The problem is that Cernera has recently learned (via a friend’s Facebook post) that you can function just fine with only one kidney, so his Facebook friend donated her other one to save someone close to her.

Most people would probably read that post, process it, and move on, but something in Cernera doesn’t allow him to do that. Instead, during the time he usually reserves for clearing his head so he can act more selflessly, he’s stuck ruminating on how not giving away his own kidney seems somehow selfish.

That’s a startling and not particularly inevitable conclusion, but it’s the one he keeps coming back to. Oh, this is a fucking nightmare, he remembers thinking about being trapped in this mental loop.

Cernera is already coping with plenty of other things. He’s 33, six years sober, and about a year out of a divorce. He’s new to Long Island, having taken a demanding financial-consulting job. As for whether or not to give up that kidney: Donating blood makes him squeamish, and he hasn’t ever broken a bone or had major surgery. It feels like a leap.

“So here I have to do all my little Buddhist sayings about how I’m gonna be kind and I’m gonna save all sentient beings,” he says later, only half joking. “And I’m sitting here going, You have a kidney and somebody else needs it, and you don’t need it at all.”

After a few weeks of contemplation, Cernera makes an even more startling decision. Since he doesn’t actually know anyone who needs a kidney right now, he contacts the Northwell Health hospital in Queens and volunteers to donate one of his kidneys to whomever the medical team chooses. He’s given the option of donating anonymously or having his name made known to the recipient, and he opts for anonymity because he doesn’t want anyone to feel indebted to him.

When the hospital does his mandatory psychological evaluation, he’s still struggling to articulate this compulsion to proceed. “I found I had to be very careful the way I talked about this,” he says. “This sounds wrong, but it is part of it: I felt like I had to do this.”

This is not a particularly illuminating explanation, especially because why people think they do things and why they really do them are often very different. But Cernera hasn’t yet realized that his fixation will spread. Over the next several years, he will give away not just one part of his body, but a second and a third, until he becomes perhaps the country’s most prolific living donor. A person, but also a Human Giving Tree: the man who literally gives himself away, even as he’s running out of things to harvest.

“I’M PROUD OF one set of scars, and I wish I didn’t have the others,” Cernera says on a recent day as he points to a series of white notches across his forearm. “I did a lot of self-harming as a kid,” he explains about where he used to cut himself. “All on one arm, because I’m right-handed, so it was all lefty.”

Cernera, now 40, is lean, with a bald head and a close-trimmed beard, and wears a set of wooden Buddhist prayer beads. He speaks in a cheerful way, even when cussing, giving him a punkish Mister Rogers vibe. These particular scars remind him of “a time when I wasn’t very emotionally regulated and it was very sad,” he says, whereas the other scars he has are from his various body-part donations.

They include a couple-inch line that runs horizontally across his lower abdomen where his kidney was removed, and a thicker, vertical one down his entire abdomen where doctors took out a portion of his liver. (In between those procedures, he did a type of stem-cell transplant, too, which didn’t leave a mark.)

But this second set of scars might not exist without the first. As Cernera tells it, he grew up in the picturesque town of Fairfield, Connecticut, the oldest of four siblings, deeply loved. He also had depression. “I was sad for no good reason. I was sad because I have a chemical imbalance, right?”

This depression became a “tricky beast” that still whispers in his ear. “It has this weird thing where it tells you that your life is worthless and hopeless and there’s no meaning,” he says. As a teenager, he once swallowed “a few bottles of pills” and woke up two weeks later in the hospital; nearly a decade after that, in 2009, at age 27, he was married and drinking a fifth a day when he checked into another hospital because he was picturing ways to kill himself.

He already took antidepressants and had started therapy, but that’s never felt like enough. After his hospitalization in 2009, Cernera committed to an alcohol-dependence recovery program and the 12 steps and, thanks to stumbling across a YouTube video of a robed monk talking about the meaning of suffering, to an intense study of Zen Buddhism. In doing so, he discovered a new way to live: Both disciplines suggest that you can overcome suffering by finding meaning and purpose in service to others. He began with small acts, like making the coffee before 12-step meetings and listening more closely to friends. “It feels good to do good, right?” he says.

There’s real science behind that thinking: People who perform kind acts receive a so-called “helper’s high” of mood-boosting endorphins, which may partly explain how our ancestors built cooperative societies. And Holocaust survivor Viktor Frankl, Ph.D., founded an entire school of psychotherapy (logotherapy) that recognized meaning as a vital factor in mental health.

Cernera finds Frankl’s 1959 book, Man’s Search for Meaning, important because, as the author describes in his autobiographical account of enduring Nazi concentration camps, helping others in bleak times can shift your view. “There were prisoners in [the camps] who gave their last morsel of bread to the other person who was starving,” Cernera says, because it was a way of creating hope.

Some of us may even be predisposed to extreme acts of good. Abigail Marsh, Ph.D., a psychology professor and the director of Georgetown University’s Laboratory on Social & Affective Neuroscience, has used MRI scans to show that kidney donors and heroic rescuers both have, on average, an increased volume in a part of the brain called the amygdala. This may give them “a strong empathetic response to others’ fears,” she says, making it easier to put others before themselves despite the risk or pain. (Additionally, other research has shown that it’s not uncommon for organ donors to have depression, perhaps because they rate high in empathy.)

Cernera added each good deed to a mental résumé that helped reinforce his value to others. Eventually, he wasn’t just doing the 12 steps; he was helping people stay accountable. He took vows at a Zen monastery upstate and began sharing meditation lessons through an online training group. By the time he learned about the possibility of donating a kidney, though, he could feel his hopelessness rising. “It was consciously like I need to do something that matters,” he says. “I need to do something that’ll make me feel better.”

The surgery took place in early January 2016 and lasted about four hours. First, Cernera was anesthetized. Then a surgeon cut three small laparoscopic incisions in his abdomen and removed his left kidney—carefully bagged—through a couple-inch incision along his pelvis. When he woke up, the sensation was “the most painful thing I have ever experienced,” he says. He healed quickly, going skydiving 27 days later, but got tired easily and for months had a general sense of malaise. Not wanting to seem self-aggrandizing, he didn’t tell a lot of people about the surgery.

And then? He just felt empty.

What Cernera didn’t know was that while he was out on the operating table, a 52-year-old named Lance Morgan was lying in the same hospital, in desperate need of a kidney.

Morgan, originally from Jamaica, lived in New York City, worked as a plumber, and had raised several kids. Seven years earlier, in 2008, he’d begun to feel “really, really, really sick,” he says. “I remember I was driving in Queens and I started to bleed through my nose, and I went to [the hospital] to figure out what was going on. They told me that I’m going into renal failure and I’m going to need dialysis.”

He received treatment three days a week while awaiting a transplant, but none of his family members stepped forward because they didn’t trust the medical system. By late 2015, Morgan had been readmitted to the hospital, and he wasn’t sure he’d ever walk out again, until a nurse shared the unexpected news.

“They say, Lance, I got a kidney for you. Hurry up and get better,” he says. “And I’m telling you, that’s the best feeling I ever had in my whole life.”

But Cernera? Empty.

MOST PEOPLE WOULD never react to pain and emptiness by contemplating the possibility of giving away another part of their body. But in mid-2017, about a year and a half after donating his kidney, Cernera found himself fixated on the untapped potential of his stem cells. Specifically, the blood-forming ones that orbit through your circulatory system and are produced by bone marrow. These infinitesimal bits of genetic flotsam divide quickly, creating blood cells (red, white, and platelets) at a rate of 500 billion a day.

The odds of finding a nonrelative who is a match for your stem cells are about one in a million. But if a person is sick from a blood cancer like leukemia or multiple myeloma, you might be able to help them rebuild their immune system, ultimately saving their life. At first Cernera wasn’t thinking about any of this, but then he received a surprising call from a representative of Be the Match, a national marrow-donor matching program that sends potential donors home test kits for DNA analysis.

While there was never some grand plan to donate more and more of himself, he had submitted a sample to Be the Match a decade earlier, on something of a whim. As he remembers it, his then wife read about the idea online and requested kits for them both. “It was kind of trendy at the time. I didn’t think about it much, to be honest with you,” he says.

Now his stem cells had matched with an unknown patient. Doctors wanted to do what’s called a peripheral blood stem-cell transplant, which would entail receiving several days of injections with a bone-marrow stimulant to put his stem-cell factory into overdrive and then undergoing a process called apheresis: Over four or five hours, they’d take blood intravenously from one arm, run it through a machine, and return what was left to the other arm.

“So that was an easy yes. Of course I’m going to do this,” he says. But only because it had to be better than giving away that kidney. “I understand why I made the decision, but it didn’t do what I was hoping it would do,” he says about the kidney donation not feeling as meaningful as he’d hoped.

Between his kidney donation and the stem-cell call, Cernera focused on other ways to feel more alive. He took a more flexible job and let his apartment go, moving into a retrofitted Ford 250 cargo van. He donated the remainder of his belongings to a women’s shelter and began living out of rest stops and Walmart parking lots during the week, so he could spend weekends traveling to meditation retreats or going skydiving.

Best-case scenario? He’d found nirvana by rejecting the outside world. “People get more enduring satisfaction from experiences they have rather than things they possess,” says Tom Gilovich, Ph.D., a psychology professor at Cornell University.

Worst case? He was suffering some kind of nervous breakdown. Such quests may help you shed the “clutter” of your life and mind, says Gregory Scott Brown, M.D., a psychiatrist and Men’s Health advisor, but giving away valuable things and becoming more disconnected from others could be a warning sign of suicide, especially if the person doing it doesn’t seem to be planning for the future.

While his actions may have looked concerning, Cernera calls this time of wanderlust the happiest he’d ever been. He loved meeting other adventurers and had begun studying for a doctorate in human development, an interdisciplinary field about how people grow and change, with the idea that he might teach someday. But he’d also given up sobriety, drinking with friends after some jumps. The drinking “was still under control,” he says. “But in the back of your head, you know it’s a fucking problem.”

Still, in mid-June, he showed up to donate his stem cells at the Geisinger Community Medical Center in Scranton, Pennsylvania. Once again, he would be given the option to share more about himself with the recipient, but he didn’t need to think about it yet. He’d find out in a year if the transplant had been successful. The injections gave him headaches, and the apheresis left him a little fatigued, but he soon got back on the road.

What he didn’t know this time was that roughly 2,700 miles away in Redlands, California, a 64-year-old woman named Jill Tracey was waiting on this transplant as her last-ditch chance to survive leukemia.

Jill Tracey, who received Cernera’s stem-cell donation, celebrates the first anniversary of the procedure, in mid-2017, that helped her survive leukemia.

In August 2015, the former stay-at-home mom and grandmother had collapsed in a parking lot. She was transported to Loma Linda Hospital and hooked up to a machine to filter her blood, which had an abnormally high number of white blood cells. “It was almost like The Twilight Zone,” Tracey says.

Several rounds of chemo failed to put her in remission, so in mid-2017 she transferred to another hospital, hoping to receive a “chemo bomb,” an ultrahigh dose of chemotherapy that would destroy all the cells in her bone marrow. But in order to be effective, it would have to be combined with a stem-cell transplant to kick-start new healthy cell growth, which presented a major issue.

“They said some people have to wait years for a donor and end up dying,” Tracey says, laughing dryly. Instead, a week later, the team had found a donor.

About a year after donating his stem cells, Cernera says he’d all but forgotten about it when a Be the Match representative checked in to say the recipient was doing well and asked if he’d like to get in touch. Perhaps it was because giving the stem cells had been a far easier and more abstract experience than donating the kidney, but the idea of meeting this stranger didn’t seem particularly daunting, just cool. He decided to make contact.

“She sent me all these pictures because she was celebrating this new life she was given,” he says about talking to Tracey. “And she’s got my cat and dog allergies! It was really hysterical.”

Cernera’s early stance about not meeting his kidney recipient makes sense to Georgetown’s Abigail Marsh, who says that organ and blood donors tend to score unusually high on the humility scale, an attribute that helps them think of everyone as equally deserving of aid. But by mid-2018, Cernera’s time on the road had allowed him to see at least one unintended side effect of that stance more clearly: “I really denied myself any of the positive feedback” from the person who received his kidney, he says.

Talking to Tracey only affirmed this. Today he still wonders whether, if he’d done things more openly and met his kidney recipient as soon as possible, he might have been able to stay sober and more connected with the recovery community.

Cernera had been told after that operation that his kidney recipient was open to meeting him, so he contacted the hospital where he had his surgery and asked if they could put him in touch. In late 2018, he called Morgan, who invited him to his home in Queens. “He has raised a family,” Cernera says. “He takes care of his extended family in Jamaica. He’s just this really sweet human being.”

He pauses, thinking about what this means to him. “I wish I had known sooner,” he says. “Because I’m really grateful to have been part of that story.”

CERNERA BEGAN FIXATING on his liver the second he left Lance Morgan’s house. It’s your body’s largest internal organ, a wedge-shaped vessel that performs hundreds of essential functions, including detoxifying the blood and generating bile to carry waste and aid in digestive processes. Most importantly for transplant purposes, the liver has two lobes and the ability to regenerate, so doctors can cut off a portion and it will regrow, allowing him the chance to save a person dying from liver failure.

Cernera’s reaction might seem unusual if not downright bizarre for someone whose previous major surgery haunted him for years, but anatomically at least, the choice made sense. Anyone who has ever researched organ donation by living donors knows that only the kidney and liver are really discussed. In the medical community, people who give up both are called dual or sequential donors. This is typically the limit of what any living donor can give—unless you get Cernera-level lucky with something like a stem-cell match. It seemed like the last major bodily offering he could make.

“It wasn’t even on my mind driving to Lance’s house,” he says about the impulse to give someone this final piece of himself. “But when I heard his story and I left, I immediately was right back to that same place I was after I first heard about kidney donation.” Except this time there seemed to be less to ponder. How could I not do this again if I see what a difference it makes? he remembers thinking.

We’re still learning what exactly drives sequential donors to give. Since the mid-’90s, there have been only about 150 of them in the U.S. Many work in helping fields or have an overwhelming desire to assist others, and they commonly have a loved one with a chronic illness, says Jennifer Steel, Ph.D., director of the Center for Excellence in Behavioral Medicine at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC), who has surveyed many of these donors, including Cernera.

Cernera fits that mold. When he was 11, his mother was diagnosed with stage 2 breast cancer and underwent a dual mastectomy and chemotherapy. Years later, around the time he first contemplated donating, he was working in an office building that had a dialysis unit on the second floor, and seeing patients pass by reminded him of his mother’s ordeal. “I could tell that they were suffering,” he says.

Changing his mind after what he calls the initially “bad experience” of giving a kidney makes sense, too. Marsh has met several organ donors who had “unexpected blues” following their surgeries, as any of us might after a major life event. For sequential donors, having a “great experience both psychologically and physically” may encourage them to donate again, says Steel.

Cernera hadn’t necessarily felt that way, until his interactions with Tracey and Morgan helped him reframe his view. Marsh calls this the “fantastic hack” of being altruistic. “Once you know how rewarding it is to help people, you keep doing it,” she says. You’ve created a virtuous cycle.

The liver donation would be his hardest surgery physically, but there was a complicating factor: Obviously, you can’t give away part of your liver if you’re actively drinking alcohol. So in early 2020, Cernera tried to get clean again, going back to 12-step meetings. His parents were divorced, and when the pandemic hit, he moved in with his mother, Ruth Rolander, for a short time to quarantine.

Ten months later, he was once again sober as he was wheeled into a bright operating room at UPMC and put under anesthesia. Over the next seven hours, surgeons would cut him open from belly button to sternum, then remove his gallbladder completely in order to access and shear off roughly two thirds of the larger lobe of his liver. If everything went okay, Cernera had already decided that he’d like to meet the recipient.

But he was terrified by one nagging thought as he drifted off: “What if this isn’t enough?”

What he didn’t know yet—at least in that moment—was that elsewhere in the hospital there was a 70-year-old man named Martin Yucha, who had beaten liver cancer only to be told that he might die anyway. There simply didn’t seem to be enough time to find a donor organ.

A former industrial engineer, Yucha had retired to hunt and fish in his outdoorsy community of Warren, Pennsylvania. Around Thanksgiving of 2016, he went to visit his son Trevor’s family in Maui. “I started getting sick on my flight back. I thought I was having a flu,” he says. By the time he landed, he felt much worse.

A visit to a walk-in clinic was followed by a battery of tests, a diagnosis of liver cancer, and chemotherapy. By late 2019, he was in remission, but his liver had been destroyed, and his doctors were struggling to locate a replacement. “They said that there was no hope for me,” he says. “I didn’t think I was going to make it to spring.”

Not long after, he was notified that the hospital would receive a viable organ shortly. Instead of waiting for a deceased donor, they’d found a living person willing to walk in and be cut open.

Three months after their surgeries, Cernera and Yucha met in a park near the hospital where they were admitted. It was a chilly day in February 2021, peak Covid, so both wore face masks as they sat on a bench, while Yucha’s wife, Barb, shared framed photos of their kids and grandkids.

It was a moment the plainspoken Yucha still finds hard to put into words. “What a guy,” he says of Cernera. “Oh, my goodness. What a lifesaver.” Today, Yucha is back to hunting from tree stands, playing golf in his senior league, and driving a van part-time for schoolkids. “I wake up every day,” he says, making clear that this alone is a gift. “It’s just awesome.”

Cernera seems to appreciate Yucha just as much. “He always calls me his brother,” he says. “It’s an incredible way to have a friendship with somebody.”

But he doesn’t downplay what the recovery took, either. Cernera had to spend eight days in the ICU and another five in a hotel next to the hospital before he could even drive home, then months regaining strength and mobility. His mother, a former hospice chaplain, looked after him and believes these donations came at a good time because they helped her son define who he is. “You know, we have a narrative about ourselves, and then there’s what we actually live out,” Rolander says.

The worst part of recovery was Cernera’s first night in the ICU, once his nerve blocker wore off. He was on another medication, but the pain was so excruciating that he wished he’d never had the surgery. Then, around 6:00 a.m., a nurse found him and held his hand for an hour until his mom arrived to take over.

“It was the greatest act of kindness I’ve ever had,” he says. “I was so scared and in so much pain, and she didn’t let me be alone.”

This was another form of compassion, and he accepted it.

HE FIXATES ON much more now. It’s midafternoon, one day this past winter, and Cernera sits on a cushioned chair as sunlight filters through a set of windows in his childhood bedroom. To answer the nagging question: “I’m grateful I did it,” he says of all his donations. “I feel done. I feel like I’ve done my part.”

Yet he’s continued thinking about how to help people in other ways, which meant deciding to move back here, with his father, as he saves money for a career change. He’s working as a fundraising executive for a children’s hospital, but, in addition to the doctorate, he’s studying to become a licensed mental-health counselor, which will entail a massive salary cut.

He’s still sober, and he’s staying intentional about many other things, too. When we drive around town, he often taps the brakes on his Prius to let others merge ahead. In the evenings, he’s been spending time with “friends”—hospice patients—something he’s done for years but feels he understands better now.

“When somebody’s suffering, you can’t take that away, right? But you can let ’em know that they’re not alone. And you can be there with them,” he says. “And it’s not just be there, as if the just is not enough.” He may not have other parts to donate, but knowing he can’t save everyone makes being present feel even more important. “Literally the most powerful thing you can do for somebody who’s dying is let them not be alone,” he says.

A thin mat sits near a lawn-ornament-sized Buddha statue and some unlit incense. If he had more time, he’d settle in to meditate more traditionally, but instead he relaxes his body, letting his shoulders drop, eyes half closed in soft focus. His body is in rougher shape than it was a few years ago. His blood pressure went up after giving the kidney. After the liver, he became hypertensive and has to take medications. There’s muscle binding in his abdomen that can pinch uncomfortably, and the whole no-gallbladder thing creates some digestive issues.

Cernera falls silent. He’s breathing slowly while counting to ten in his head. He inhales… one. And then exhales… two. When he’s interrupted by a passing thought, he starts the count over, refocusing on his breathing. Soon time seems to slow down as each full breath—the inhale and the exhale—becomes a single beat. He knows he won’t make it all the way to ten but keeps starting over regardless.

After a little while, he opens his eyes, looking refreshed.

When we talk again days later, he asks me a question that anyone familiar with his journey might be asking themselves at this point.

“Have you thought about giving a kidney?”

Whatever the answer may be, he’s not judging. There are many ways to be of service. It seems like one of the simplest things he can offer anyone now is this opportunity to consider the question for yourself and think about where it might lead you next. Take your time. You don’t have to answer immediately.

“Contemplation is the important part, right?”

Ben Paynter is the Features Editor of Men’s Health

Comments are closed.