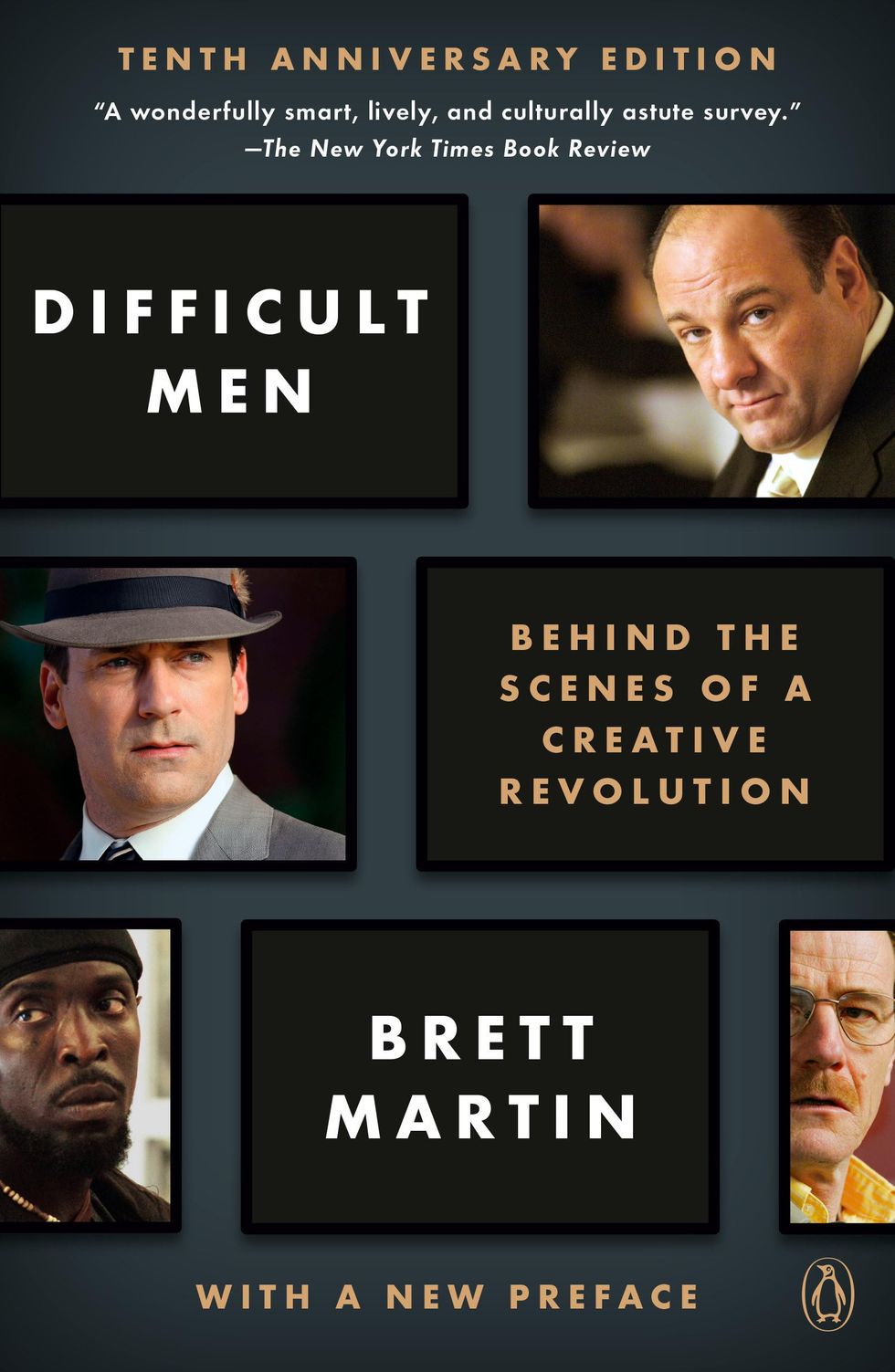

TONY SOPRANO, DON Draper, and Walter White might as well function as modern television’s holy trinity—although their behaviors are anything but saintly. These three protagonists became the poster men for a golden era of modern television, and were defined by the creative men behind them—David Chase, Matthew Weiner, and Vince Gilligan, respectively—for good or for ill. That’s the theory that writer Brett Martin posited in his 2013 book Difficult Men, which charted a rare peek behind the creative curtain, showing how the sausage got made for television’s “Third Golden Age.”

In the early and late aughts, television became the behemoth it is now largely on the back of Chase, Weiner, Gilligan, and others like The Shield’s Shawn Ryan and The Wire’s David Simon. Martin’s book offered incredibly compelling insight into the men behind the men and how their work redefined the medium. But it’s also an unflinching look at how ill-equipped some of these creatives were at actually managing people. Sure, they could write the hell out of a show, but that didn’t mean they were always model employees for their respective employers. Martin’s book felt like you got to sit in the middle of a writer’s room and experience—warts and all—the process in which these iconic shows come to life.

To mark ten years since the book’s publication, an anniversary edition of Difficult Men recently arrived on bookshelves with a new preface that offers a succinct look at just how radically the industry changed in the following years. Men’s Health sat down with Martin to talk about that preface, where the “Difficult Men” archetypes are now in the wake of the book’s initial publishing, the impact of the writer’s strike, and much more.

Men’s Health: How did this particular ten-year edition come together?

Brett Martin: I was shocked and horrified to see that 10 years had gone by [laughs]. That’s the first part of what happened.

Sometimes 10 years is just a random number, and sometimes it feels like, “Oh, look, there’s a circle being closed here.” In this case, there seemed like a lot of circles being closed. The conditions that created what I call the “third golden age” were being exposed by the Hollywood strike, which was really on the horizon when I was writing that preface, but has now obviously taken over the discussion. The ways we look at workplace conditions and the way that bosses are allowed to act had completely revolutionized, coming to a head in the last couple of years. And this idea of being smothered in quality—as opposed to being so hungry for it—which is really what my book is about.

There’s a sense now that we’re drowning in it. In fact, it’s become this sort of unsustainable, untenable situation. I feel like there, on a personal level, was a chance to try to get in front of more people. I’m quite proud of it. The stories in there stand up and are fascinating.

How do you think the Difficult Man as a character archetype has evolved over the last decade?

By the time the book came out, I already—in some ways— was of two minds about it. I write in the preface that there was, very clearly, the trope that launched prestige television: these men who were anti-heroes, who were the kinds of characters you’d never seen on television before, because they did explicitly bad things, were explicitly problematic, and they challenged the way we watched, that natural loyalty which we extended to charismatic characters and protagonists. They made—I described it as, this queasy relationship to their behavior, wondering “What the hell is the matter with us?” because of it. That was the driving force. I came to believe, and still believe, that what we were seeing was the birth of well-written characters.

Their masculinity, on the one hand, was super vital to this cultural moment, but it was also, in other ways, incidental that what you were seeing was being allowed to write characters that were contradictory, like [how] we’re all contradictory, that we’re on journeys that don’t go in one direction. None of our journeys go in one direction. The kinds of characters that it was not unusual to see in film or in literature, but because of certain commercial conditions, had never really been allowed to flourish on TV.

Do you think there was a specific point at which audiences became more willing to wholeheartedly accept these characters? I ask because I find the sort of “BabyGirl”-ification of Kendall Roy in Succession very fascinating. It makes me think a lot about how people have embraced characters like him, Tony Soprano, and Walter White and feel very protective of them. Do you think that’s because audiences can better look at the nuances of the characters and see the gray there versus a black-and-white binary?

That’s the exact same dynamic, [but] it’s been deepened. We’ve seen infinite variety of that by now, but it’s harder to just love or hate a character when they are being presented as fully-rounded human beings. It’s hard to remember how it felt to first go through that process with Tony Soprano on television, because you hadn’t been asked to wrestle with that question before. We take it for granted that you’re going to find great characters like that on TV. But it was really this nauseating whiplash. Walter White was as explicitly an example of that, where you found yourself defending and rooting for characters that you knew very well didn’t deserve to be rooting for. What you’re describing with Kendall Roy is precisely the same dynamic.

Do you think there might be a point where audiences start rejecting these complicated characters in favor of something a bit more black and white? I just think about how certain sectors of the Internet responded to, for example, Oppenheimer age gap discourse and wonder if we might see the pendulum swing the other way.

What we’re talking about is still a small segment of the entertainment ecosystem. The numbers have never been anywhere near equal between these shows that we’re talking about that get all this cultural capital in terms of actual eyeballs. [There’s] this entire shelf of still ongoing, somewhat simple-minded, network television, [where] you can still watch plenty of the good guys and bad guys. You always have been able to, and many more people do.

Ted Lasso was following a similar pattern to what you’re describing, where it was a relief not to have to wrestle with these demons for a little while. The backlash against more than one season of that suggests for those people used to more, it got old in a hurry.

As someone who spent a lot of time around television writers, how optimistic are you feeling about the writer’s strike?

I don’t have a crystal ball about it at all. I really don’t know. It’s hard for me to fathom that we got here, frankly. What stands out to me, more than anything, is how the conditions that created what I celebrated as this great flowering of creative work have been now either devalued, intentionally thrown out, or proven to be hollow. It’s depressing.

That [creative work] was at the heart of what created the conditions for this world of television, [it] was some recognition on some level [about] the value of artists. There was this wonderful moment where corporations needed them badly, and where the forces of art and commerce aligned.

There’s been a few of those, and it seemed to me that streaming was just another. In a world of infinite media choice, you needed to differentiate yourself. In order to do that, you needed artists. Then there’d be some reasonable redistribution of wealth from corporations to artists to do that. I’ve been amazed and shocked at how much that has been betrayed.

To your point about artistry, do you think we’ve seen creatives in the streaming era become household names in the same way people know David Chase or David Simon?

That’s the other flip side. Donald Glover and Atlanta is very much a delivery on the promise of this era as anything else. Reservation Dogs is. The Leftovers was. These aren’t streaming shows, but I feel as though the whole trade-off here is that we saw a thousand flowers bloom over the last ten years, in terms of the work. The work has been incredible and, in every way, a delivery on the promise. Which is what makes it all the more dispiriting than it seems to have been done on a hollow and inequitable economic model, you know?

I have no doubt that those people are out there. That was the other premise of the book to begin with, this ferocity and appetite with which artists fall on opportunity the moment they’re given it. I don’t think that has changed or will change. There are a lot of people who have stories out there, who I imagine are instinctively looking for opportunities. Are there certain moments where things will converge and allow them to tell them?

Of the shows you wrote about, is there one that you find yourself coming back to time and time again? And if so, why?

I’ve never been a binger, and I’ve never really been a re-watcher. It’s a handicap in this job. I have found myself thinking about Mad Men more than any other in these past five years. It’s specifically because of the ways in which it nailed what it’s like to live a small human-scale life among the giant tides of history. It was almost sort of a third theme of the show. It wasn’t really the thing that was out front if you [were to] say, “Well, what was Mad Men about?” but it feels just like when we’ve had the television playing in the background with news of the most outlandish kinds of historical events, and I’m busy dealing with my own petty frustrations about something.

I feel like that’s what it will be remembered for getting more right than anything else. We’ve lived through times certainly as turbulent or more turbulent than the ’60s in the last five or six years, and he was right about that.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

William Goodman is a freelancer writer, focused on all things pop culture, tech, gadgets, and style. He’s based in Washington, DC and his work can also be found at Robb Report, Complex, and GQ. He’s yet to meet a jacket or cardigan he didn’t love. In his free time, he’s probably on Twitter (@goodmanw) or at the movies.

Comments are closed.