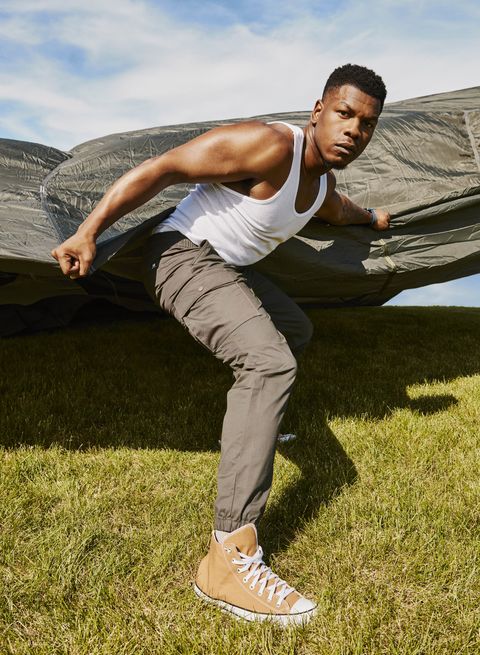

HIGH IN THE manicured hills of Pomona, New York, a bucolic suburban town in a galaxy far, far away from bustling Manhattan, is where you’ll find John Boyega quietly idling next to an infinity pool. For the better part of a five-hour photo shoot, Boyega has been “on,” flexing his newly won biceps and striking poses with a billowing parachute. “I feel like I’m in an Adele video,” he jokes at one moment, crooning “Helloooo” and serving up blue-steel gazes from the driver’s seat of a Day-Glo-orange McLaren GT. When he’s not dancing to Burna Boy, he’s switching in and out of Gucci tank tops and gam-hugging hoochie-daddy shorts by Dior. He has indefatigable energy and is downright silly, which comes as a complete surprise to those of us who know him only from his sober turns in an epic franchise and several critically acclaimed indies. You would never guess that he’s fresh off a flight from London, sleep-deprived and starving. In fact, when I ask him how he’s feeling, he flashes the type of winning smile that makes knees buckle and hearts skip. “I feel sexy,” he declares. “I can’t lie. I feel very, very sexy.”

Days later, when Boyega talks about the feel-good vibes he emanated on set, the 30-year-old grows philosophical. “You have two options as an artist,” he says. “Fixate on your fatigue or acknowledge that you’ve arrived and express your extreme gratitude. When I was broke and no casting director wanted to see me, if someone said, ‘We’re going to fly you out tomorrow, take care of your hotel, shoot a Men’s Health cover, then fly you back,’ I would’ve cried with joy. Yeah, I just got off a flight, but that’s what the rappers sing about. I’m living it.”

These are indeed the moments Boyega, the British-born son of Nigerian immigrants, dreamed about as a lad in Peckham, a working-class community in London. Back then, he regularly practiced being late-night-show charming in his bathroom for future interviews, which helps explain why he’s so affable when chatting about how this year promises to be a big one for him. He’s part of a new wave of actors of African descent who are storming Hollywood—Daniel Kaluuya, Lupita Nyong’o, Chiwetel Ejiofor, and Damson Idris, to name a few. West African culture—Nollywood movies on Netflix and Afrobeat on the radio—is also enjoying an unprecedented level of visibility. Boyega has three major films hitting theaters in the coming months: Breaking, The Woman King, and They Cloned Tyrone. Then there’s his work with his company, UpperRoom Productions, which has already inked development deals with Netflix and ViacomCBS.

Boyega’s returning after an emotionally crippling rough patch in 2017 that found him contemplating quitting acting. No time off between back-to-back projects—Star Wars: Episode VII, Pacific Rim: Uprising, and the stage play Woyzeck (in which he played the title role)—left him feeling “exhausted, frantic, and paranoid,” he says. “You’re tired by your own dream, what you love.” He took a hiatus to recharge and to work on building a better version of himself, one who was stronger physically, mentally, and spiritually and ready to embrace leading-man status and the high visibility that comes with it. During a break on set, he stands in front of a monitor and stares at images of himself in a yellow windbreaker. He’s traded his signature cornrows for a clean fade, and the actor who was once described as “being built like a bullet” has leaned out considerably, as evidenced by his prominent cheekbones and sculpted frame. He’s impressed. “That’s real Black-boy joy,” he says gleefully. “Black-boy joy!”

BOYEGA HASN’T always felt so great about his own body, he admits while on a road trip the day after the shoot. We’re driving from New York City to test-drive the 1965 Chevrolet Corvette he’s just purchased from Motorcar Classics in Farmingdale, on Long Island. He already owns a Lamborghini Urus that he keeps in London and a Jeep Wrangler Rubicon at his home in the Caribbean. His newest whip will stay in America.

Boyega is upbeat on this overcast day, as giddy as a kid on Christmas morning. He’s in a sharing mood and riffs about his childhood. His family, whom he’s always been extremely close to, grew up “without money.” Peckham was filled with fast-food chains and liquor stores, and Boyega was “chunky as hell,” he says. “Not fat fat, but I hated being topless because I had a little bit of a hanging belly. I gained weight in the most awkward of places while everybody was looking athletic, ripped, and lean.”

Proud of his Nigerian heritage, the actor has an autobiographical sleeve tattoo on his left arm, beginning at his shoulder with an image of Africa (highlighting his homeland) and winding down to two beautifully rendered depictions of his parents just above his wrist. They immigrated to England in the 1980s. “My mom and dad will always be my heroes, because at the end of the day, man, they made the fundamental choice moving from Nigeria, coming over to London,” he says. “If they didn’t make that choice, I don’t think any of us would be here.”

Amid the elaborate ink tableau is an image of a lion that Boyega says represents his dueling spirits. “I like to fight and I like to cuddle,” he says, before bursting into laughter. His father, Samson, a Pentecostal minister, and his mother, Abigail, a caregiver, have been married for 35 years, and he has two sisters, Grace and Blessing. They’ve championed his work ever since he first appeared onstage in an update of the African folktale Anansi the Spider in primary school. “I used that as an opportunity to crack jokes and flirt with the girls—it was cool.” He enjoyed the attention and the crowd’s positive reception.

Soon Samson was taking his son, born John Adedayo Bamidele Adegboyega, to kiddie auditions at local performing-arts centers in London. In those formative years, Boyega learned to deliver Shakespearean monologues, tap-dance, and plié, and he perfected his American accent by studying rom-coms like The Best Man and Idris Elba’s portrayal of Baltimore drug dealer Stringer Bell on The Wire. He honed his quick-wittedness at Westminster City School, a state-funded secondary academy for boys. “Every other morning, [classmates were] cussing the size of your head, the size of your ears. If you don’t know how to snap back, you might end up in some sadness. You have to take a joke, too, know how to laugh at yourself and understand why people may be laughing at you, and then be like, ‘You know what, if I wasn’t me, I’d probably be laughing at this shit, too.’”

Femi Oguns, Boyega’s drama teacher turned agent, first observed his talent at Identity School of Acting, an academy Oguns founded for talent from marginalized communities in 2003. Having worked with Boyega for more than a decade, he says, “It was very evident that he was somebody that had a maturity at a very young age but also had a wonderful openness to the craft. There’s a truth that he brings to everything he does.” Boyega is drawn to scripts that inspire a visceral reaction. He knows he’s found the right one when his chest begins thumping and “I can visualize the film. The concept is clear; the intentions are clear. I’m going through each page and wishing I could read it in five seconds.”

Director J. J. Abrams loved him enough as the precocious alien fighter in 2011’s sci-fi comedy Attack the Block to cast him in his Star Wars update years later. Boyega—a huge Star Wars fan—auditioned for nearly a year before landing the part of Finn in Abrams’s trilogy. It was a life-changing opportunity that would ultimately prove bittersweet. Yes, it made Boyega rich and gave him access to front-row seats at Burberry runway shows, but it also put him in the crosshairs of racist Internet trolls who could accept a world filled with Ewoks and Wookiees but couldn’t fathom a stormtrooper of color.

The actress Moses Ingram, who stars on Disney+’s Obi-Wan Kenobi miniseries, recently endured a similar backlash, but she’s been publicly supported by her castmates, and Lucasfilm execs were forthcoming about the online abuse she could face. Was Boyega similarly forewarned? “Hell no,” he states. “I’m the one that brought this to the freaking forefront.” He says he was blindsided by the racist vitriol hurled at him, and at times it made him question if he even wanted to be part of the sci-fi juggernaut. Boyega has consistently voiced his frustrations about how his character was underdeveloped and ultimately marginalized. He remains vocal about feeling unsupported in those days, which he hopes has compelled execs to become more accountable to actors of color. “At least the people going into it now, after my time, [they’re] cool,” he says. Lucasfilm is “going to make sure you’re well supported and at least you [now] go through this franchise knowing that everybody is going to have [your] back. I’m glad I talked out everything at that time.”

His sister Grace says he’s been outspoken since childhood. “Whatever John believes in, he’s going to stand by it.” His speech at a Black Lives Matter rally in London in 2020 wasn’t planned. That day, he and Grace had intended to quietly protest about the death of George Floyd. However, one of the march organizers handed the actor a megaphone and invited him to speak from his heart. He did. In his nearly five-minute monologue, he was angry, raw, and breathtakingly honest about the trials of being Black in a world that rates him as a second-class citizen. “I need you to understand how painful it is to be reminded every day that your race means nothing,” Boyega declared in his speech, which immediately went viral and cemented him in the annals of activist artists.

“Any of us keeping our mouth shut at this point, it doesn’t really feel too comfortable,” he later tells me. “Because even if you’re British, [you’re] working in the States; the gun’s going to go off before your accent does.” His message for people still bothered by his bluntness and unapologetic embrace of the BLM movement? “Our empowerment is not your demise,” he says. Did he experience any backlash? “Of course there’s backlash. Seen and unseen,” he says cryptically. “It’s just how it goes. You’ll see who’s for you and who’s really not. . . . [But] this is who I am. I’m going to speak about what I believe in and make sure that whatever I do is aimed at supporting the people.”

Reaching this level of self-acceptance came at a cost for Boyega. “Ambition is my battery power,” he tells me. At age 19, he decided he wanted seven figures in his bank account before age 25. “I was a millionaire by probably 22 or 23.” He purchased a new home for his parents with one of his first big checks. But that ambition drove him to feel like he “had to say yes to everything” on his way up. “It’s tiring and it’s stress, and then dealing with the fact that you eventually have to perform,” he says. “There are many different ways careers can exhaust you, but the artistic way is unique.”

THE PHYSICAL part of Boyega’s post–Star Wars rebuild involved working out for 90 minutes five or six days a week with London-based trainer Tim Blakeley. His fitness regimen, a mix of cardio, weight training, and yoga, is as effective as it is excruciating. “Leg day is the worst day,” Boyega says. “All the training that I do is about detail, posture, and getting the most out of each rep.” I ask if he listens to Cardi B, Megan Thee Stallion, and the other ratchet rappers who currently fuel my gym workouts. “I’ve got a confession,” Boyega says, leaning in conspiratorially. “I rarely listen to music with lyrics in the gym. I listen to movie scores. . . . I love Hans Zimmer. I love Harry Gregson-Williams.” Epic, orchestral soundtracks from films like Gladiator, Inception, and The Dark Knight are his go-tos. “It’s harder to run on the treadmill when Drake is talking about being on the jet,” he jokes. “The workouts I do [are] hard. I need me some motivation.”

Of course, Boyega also reworked his diet. Ditching sugar was a “massive” game changer. “That’s my enemy,” he says. “Doughnuts, chocolate, candy, pie, sodas . . . the stuff that kills you. I had to get rid of that habit.” His diet now consists of Grace’s nutritious, home-cooked meals. Lots of lean chicken and brown jollof rice, a Nigerian dish made with tomato paste, onions, and spices.

Resetting mentally was perhaps the most difficult. Boyega tells me he found guidance from fellow franchise star Robert Downey Jr., who has struggled with his own challenges. “I am very interested in people who go to dark spaces and are able to flip that,” he says. Downey told him, “They’re not going to know what to do with you when you come into the industry; they’re going to be like, ‘Oh, let’s just make him well-spoken and nice.’ That’s kind of the filter. You’re going to go through some turbulence. You’re going to try to find who you are within this. It might be rocky, but you’ll come out the end with a solid identity. That’s literally what happened to me,” Boyega says.

He learned to surround himself with trusted friends and family. “You choose your circle in which you can accept how you express yourself. Once you feel that acceptance, they can help you, help motivate you. That’s your safe place as a celebrity. So you can actually complain. I still want to say that shit. Like, this is petty, but I want to tell my sisters, ‘Oh, this is just how I feel.’ And they’re going to be like, ‘This is petty, but yeah, I hear you.’ Whereas in the world it’s going to be like, ‘You’re a fucking millionaire, you idiot. You know what I had to do this morning, and you’re complaining about that?’ Let me just chill and complain to the people that understand that I’m not trying to be evil. It’s just today, I’m sad. I’m experiencing [this phase of my career] as a more balanced person who is willing to improve. I know it’s a weird, random thing to say, but I’m willing to say sorry.”

There are two main things that Boyega wanted to achieve upon entering the business. “To disrupt the industry and also to make history, and nothing has changed,” says Oguns. “For John, it was never about trying to fit into the box. He wants to be the outline of the box.” That’s why Boyega has sidestepped playing enslaved people or drug dealers and appearing in clichéd sports movies, his agent explains: “For John, it’s all about accountability. He doesn’t want to be defined by any stereotypical roles.” But there are rumors that Boyega has secretly joined the Marvel Cinematic Universe. “That’s not in the vision for me now,” he says. “I want to do nuanced things. . . . I want to donate my services to original indie films that come with new, fresh ideas, because I know it’s real hard to top Iron Man in that universe.”

Boyega describes one of his upcoming films, They Cloned Tyrone (due later this year), as a “unique and strange story that blew me away.” I admit that I’m confused by the film’s premise and ask him to make it plain. He can’t, really. “Pimp. Prostitute. Try to uncover a mystery in the ’hood. That’s all I’m giving you,” says Boyega, who plays multiple clones ranging in age from 28 to 78 and costars with Jamie Foxx, who, unsurprisingly, went a long way toward making it the most fun he’s ever had on set. “We were filming all over Atlanta, so you can imagine the energy. We in the strip clubs, we in the streets,” Boyega says. “It was a joy.”

Flexing a different kind of dramatic muscle alongside Viola Davis in the historical thriller The Woman King, Boyega plays King Ghezo, a conflicted ruler in late-19th-century West Africa. Due in theaters on September 16, it tells the story of the Dahomey warriors, a fearless band of female fighters who battled European colonizers. When he’s asked why he said yes to this project, Boyega’s eyes light up. “The fact that I would be able to speak in my father’s accent, in my native tongue, and portray something that’s different from what I’ve done before, I was like, ‘Yeah, I’m coming. I want to be a part of that big-time.’”

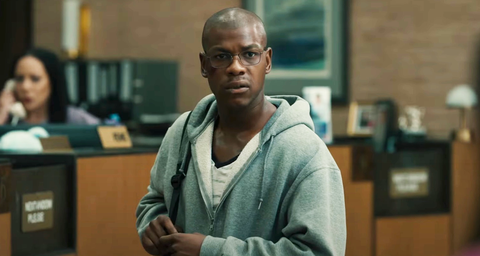

In his third major project of the year, Breaking (out August 26), Boyega stretches yet again. He shines as a diminished man abandoned by his country and fighting to maintain his dignity in the film—based on the true story of a Marine veteran whose PTSD leads him to stage a botched bank robbery. His performance is already being compared to Al Pacino’s virtuosic turn in the 1970s classic Dog Day Afternoon.

The movie gave him an opportunity to act opposite one of the titans he used to watch on The Wire, Michael K. Williams, who plays a hostage negotiator. Working with Williams, who died of an accidental drug overdose in 2021, was “phenomenal,” he says. “And when I met him, it was a full-circle moment for me.” Williams gifted him a cologne from a small Black-owned business during their first days on set. “It’s finishing, and I feel sad about it,” he says. “I always say that Michael K. Williams is the nicest-smelling man in the industry. His smell is ridiculous.”

During our nearly two-hour journey to the car dealership, Boyega has been amusing me with tales of his newly adopted roller-skating hobby—“I’m bloody freaking good. The way I turn these corners, it don’t make no sense”—as well as his search for the perfect companion. His parents’ long marriage and egalitarian partnership have been hugely inspirational. “My dad would plait my sisters’ hair while my mom was cooking,” he says. “They’re inseparable at this point.” He too wants a ride-or-die woman who’s curious, quick to laugh, and spontaneous. And, he adds, grinning slyly, “I like them thick and brown.”

Boyega and I have finally arrived at Motorcar Classics, where sleek rides lovingly restored to their youthful glory preen like pageant queens. We check out ’70s Stingrays and tricked-out ’80s Ferraris. Plus, of course, Boyega’s Corvette, a silver beauty with sumptuous red-leather interior. But it’s the Aston Martin, with its significant pedigree and the license plate JB 007, that causes the actor to stop in his tracks. Coincidence? Or could it be subtly announcing that he’s appearing in another iconic franchise soon, trading lightsabers for shaken martinis, perhaps? No, Boyega says with a wishful glint in his eyes. “But you know if they give me that call, I’ll be there.”

This story appears in the September 2022 issue of Men’s Health.

Comments are closed.