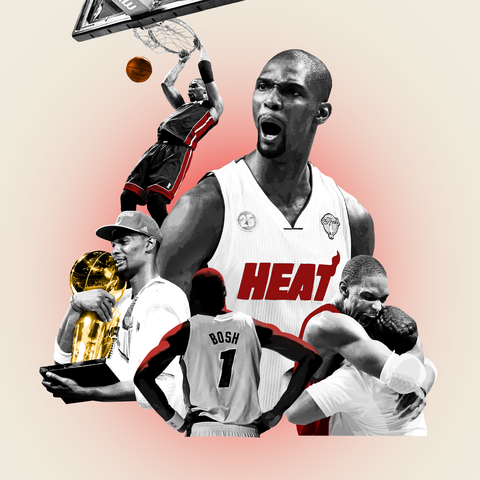

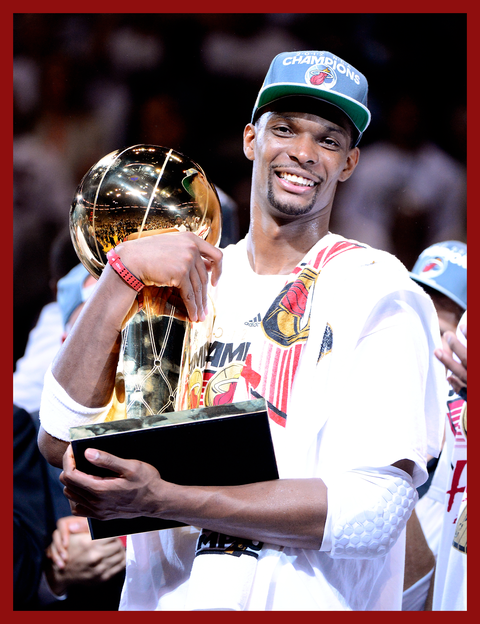

NOT LONG AGO, I was talking to eleven-time NBA All-Star Chris Bosh. He won two championships and an Olympic gold medal, and was elected to the Basketball Hall of Fame last year, but he’s suffered many losses, too.

And he wanted to talk about his greatest defeat.

Then he told me about the 2011 NBA Finals. That was the first year that he, LeBron James, and Dwyane Wade had teamed up on the Miami Heat, which was an earth-shaking move in the world of basketball. Expectations for success were unmeasurable. The Heat made it to the finals, but then, to almost everyone’s surprise, the team lost to the considerably less flashy Dallas Mavericks. “It was just crushing,” Bosh said. He cried on national TV, which he was embarrassed about. But ultimately, he and his teammates stepped back and asked themselves a version of that question: What did I just learn that I didn’t know before, and that other people may still not have learned?

The answer, they realized, was the need for emotional steadiness. Whenever the Heat won a game in that finals series, they were ecstatic. Whenever they lost, they were crushed. Their highs were too high, and their lows were too low. The Mavs stayed right in the middle, which helped them win. “We took it as a data point,” Bosh told me. And they won the next year.

That sounds great. But what does it mean exactly? In short, management experts like Susan David, Ph.D., a psychologist at Harvard Medical School, have helped popularize the idea that failure isn’t a finite thing. Each disappointing moment in your life contains a trove of information that, if viewed dispassionately, might hold clues that can help you eventually succeed.

As the editor in chief of Entrepreneur magazine, and host of the podcast Build for Tomorrow, which uncovers surprising solutions to our greatest challenges, concepts like this have long fascinated me. When it comes to defeat, you can begin by stepping back from every moment of perceived failure, as well as form every time you feel disrupted by forces of change, and ask yourself: What did I just learn that I didn’t know before, and that other people may still not have learned? It’s not an easy question. But if you drain the emotion out of any difficult or embarrassing moment, that question can help give your experience new purpose. (You can read more in my book, Build for Tomorrow, about how to harness the distinct experiences that happen to all of us as we face moments of enormous change.)

This wasn’t the only reason I wanted to talk with Bosh. Sure, he won and lost on the court—but that’s what players are supposed to do. The ups and downs of the NBA are not comparable to most people’s lives or professions. But what happened to Bosh next is very human and relatable. Bosh developed blood clots, and in 2016, a doctor determined that he could no longer play basketball. So just like that, Bosh’s career was over. He’d worked with a singular focus for most of his life, with the goal of having a long and successful career in the NBA—and then every goal and aspiration he had was torn away from him, unable to be fulfilled. He had nothing.

This isn’t a failure, per se. It was hardly his fault. But then again, change is rarely our fault. It is rarely something we conjure ourselves. But we alone must deal with the repercussions of it, which can often feel a lot like failure—if not a failure of our own making, then at least the failure of our expectations. And . . . then what?

That’s the bigger question I had for Bosh. Could failure be data in his life, and not just in a high-stakes basketball game?

Here, again, Bosh said yes.

After Bosh’s blood clots, he did what you might expect: He spent a lot of time figuring out how to get back into basketball. Maybe there was some medical treatment, or some new diagnosis, that could make this all go away? Once those paths were exhausted, he felt lost. He had always read a lot of self-help books. “I remember all those books saying, like, ‘Just do what you love,’ ” he told me. “And I was like, ‘Yeah, OK, easier said than done. Now I’m in this position and I have to find what I love.’ ”

He’d long been interested in music and books, so he started to explore that. Maybe he could write something? “I just kept doing it,” he told me. “Did it make sense at the time? No. It was very foggy. But I just continued. And I feel that, in doing those things, and staying with it, things just started kind of materializing.” A small idea turned into a book called Letters to a Young Athlete, which is a collection of advice aimed at young and aspiring athletes like he once was.

“I came to the realization that, OK, I have a choice: Is this going to help me, or is it going to hurt me?” he said. “I choose that it is going to help me. And it’s going to propel me. You know, I may be down right now. I may be out. But this situation is going to propel me to where I need to go in the future, because what other option do you have? That’s one of the main lessons that I learned as an athlete, when pursuing championships and greatness: It’s just not going to be handed over to you. You’re going to have obstacles and challenges. You’re going to have to get over them. So attack it with enthusiasm. I eventually got to the point where I joke: In writing a book about obstacles, I had to get over obstacles writing the book.”

Things end. When Bosh lost his career, his time in the NBA ended. But of course, no ending is final. Bosh, like any business owner, did not cease to exist after one phase of his career concluded. These people had more journey to travel, and more growth to explore. So they began with the information—the data!—that they had available to them. Something from before helped them orient to now. For Bosh, he expanded upon other passions like music and reading—but even more so, he reframed what he’d learned in sports, about how every pursuit has challenges that must be met. In recent years, that’s meant jumping into commentating, and also winning Twitter a clever viral moment. But he didn’t fully appreciate the power of this perspective until he was faced with a life-altering experience. That is data. The data is what will move him ahead.

“We don’t work to be average,” he told me at one point.

That’s exceptionally true. We work to be extraordinary. Along the way, we will feel out of place, struggle to grow, make hard decisions, and face massive setbacks. We will lose. We will fail. We will experience things that feel final. But this, too, is why we work: It’s so we build a stable foundation upon which we can be extraordinary in ways we may never have imagined.

This article is excerpted from Build for Tomorrow copyright © 2022 by Jason Feifer. Used by permission of Harmony Books, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Jason Feifer is editor in chief of Entrepreneur magazine, and host of the podcasts Build for Tomorrow, Hush Money, and Problem Solvers.

Comments are closed.