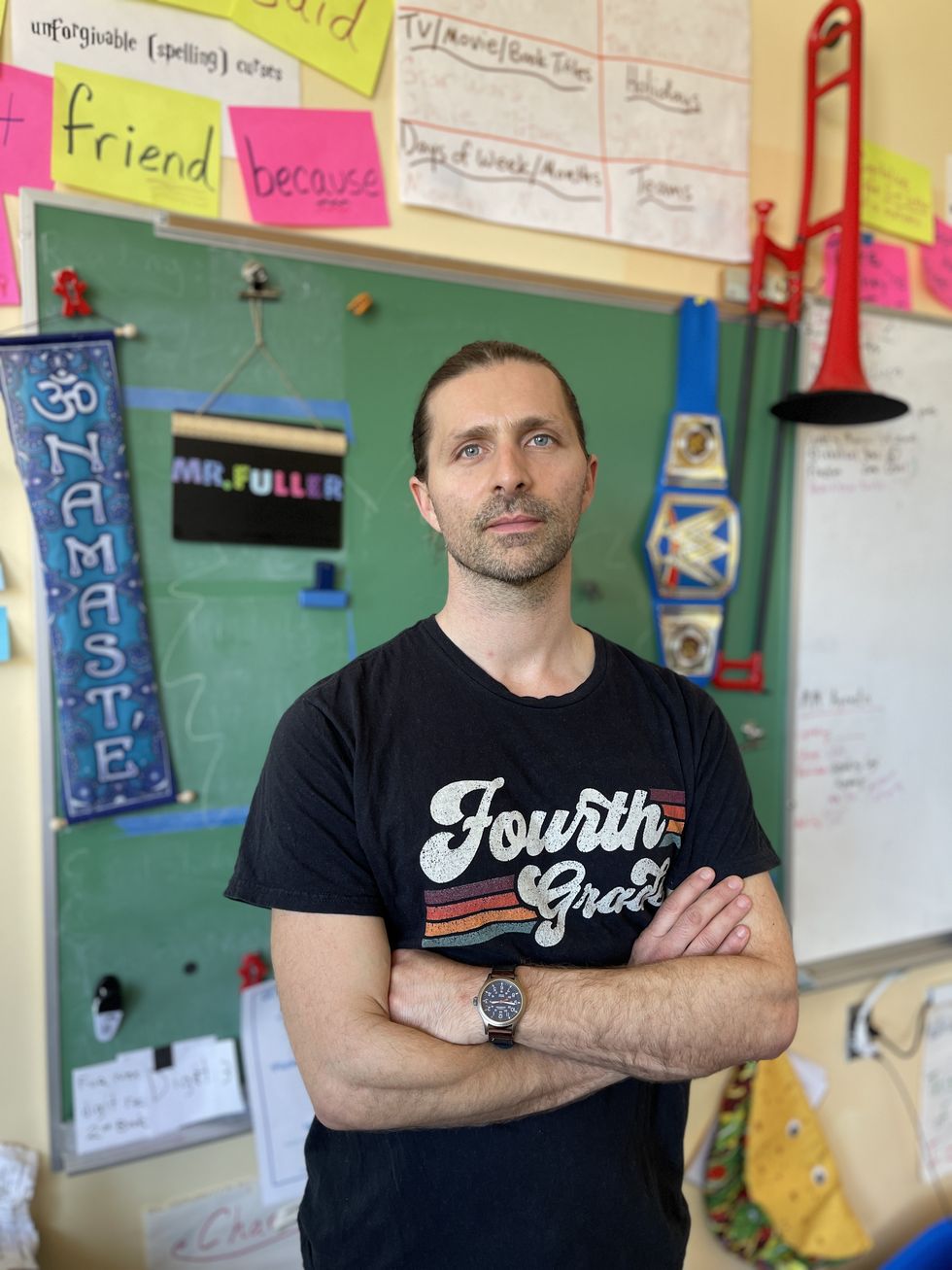

IN 2022, I was hired to teach fourth grade at a new school. I’ve taught on and off for almost two decades and moved schools often. With each move, I find myself asking the same key questions:

1) How much chart paper did the previous teacher leave me?

2) Can I control my classroom temperature?

3) How far away is the faculty bathroom?

Last summer, however, while touring my new school with the principal, I had only two burning questions upon stepping into my classroom for the first time:

Do my windows open?

Do they open wide enough for my students to escape a shooter?

From 2000 to 2021, according to the National Center for Educational Statistics, shots were fired at more than 1,000 schools. We live firmly within the Age of School Shootings, a uniquely American span on the timeline of human history. My career in education has almost perfectly overlapped this period. I think about it sometimes like a terrible eclipse. Sandy Hook, Parkland, Uvalde, and, just last week, Nashville. I became a teacher because I enjoy coaching children to develop a love of reading; to write heartfelt stories; to seek wonder at every turn. I did not become a teacher for the responsibility of keeping children alive in one of the deadliest environments in America. But between the hours of eight and three, the job—it often feels—is all mine.

After the principal concluded my school tour, she invited me to spend time organizing my classroom, which was a mound of boxes, stacked chairs, and desks. The moment she left, I beelined for the windows, where I found good news and bad.

Good: Windows open.

Bad: They are casement, “crank” windows, meaning I’d waste valuable seconds spinning a stupid handle to open them in an emergency.

Good: Windows face south, meaning direct sunlight, meaning I can possibly keep them open year-round, saving me those valuable seconds.

Bad: Winter will be cold with the windows open.

Good: My students are tough Maine kids; they can wear extra layers.

Bad: Extra layers could make it harder to squirm through the windows.

So much planning goes into the beginning of the school year. It is overwhelming, especially at a new school, with a new curriculum. I would soon have to-do lists on whiteboards and sticky notes and Google docs. But ten seconds into my new classroom, I was only thinking of escape.

I WAS TEACHING fourth grade in California during the Robb Elementary shooting in Uvalde, Texas. While 19 students and two teachers were being murdered, my 26 students were at art. The other fourth-grade teacher and I were planning for next week until suddenly we were not; her watch buzzed—a message from her husband. She told me. We stopped planning. We scrolled the news. There was nothing to say. We had been here many times before.

“Oh my God!” she yelped, looking at her watch again and jumping up.

“What happened?” I said, my every nerve on edge.

“We’re late. It’s time to pick up the kids from art.”

MY NEW SCHOOL has its first staff meeting in late August. Teachers and support personnel gather in the gym. At 8:00 a.m. we start with introductions of new hires. I stand. I smile. I wave. By 8:30 we are discussing safety protocols.

We will have two lockdown drills this year, the assistant principal explains. The first will be announced. The second might not be announced, depending on the temperature of the school. Are there any questions?

“During a lockdown, do we still cluster?” one teacher asks. “I heard clustering was out.”

“If you’re clustered together and someone enters the room, you could be an easy target,” answers the assistant principal.

The principal chimes in: “New research says it might be better to have your students scattered around the room. But in a scary moment, it might feel better to be close. Defer to what feels right for your class.”

The principal is wearing a Taylor Swift concert T-shirt. The assistant principal is wearing Mötley Crüe. The teachers around me are wearing the Who and the Grateful Dead and Def Leppard. We are dressed this way because our first meeting has a theme: THIS YEAR WILL ROCK.

SCHOOL BEGINS. I have 21 students. They are shy. They are silly. I want them to feel comfortable and have fun. I work ten-hour days to make this happen. People say that teachers execute more minute-to-minute decisions than brain surgeons. I don’t know if this is true (or if anyone says this besides teachers), but I do know that I don’t have extra neurons to spend thinking about someone entering my classroom with a gun. Even when my students are at library, or lunch, I have parents to email, work to assess, a single-elimination multiplication tournament to prep. I need to teach, laugh, have fun. I need to help 21 good little humans along the path toward becoming 21 good big humans. I don’t need to be listening for the pop-pop-pop of gunfire. I don’t need to be visualizing how I will somehow cover the space to the hallway door before a shooter enters my class. But sometimes—too many times—there is little else on my mind.

When you’re teaching in one school and you learn about a school shooting happening simultaneously at another school, your mind splits, birthing a parallel universe. In the parallel universe, the shooter is also stepping into your classroom. You see him as clear as day. You see him killing your students. You feel the weight of two or three limp children in your arms. You smell the tang of gunpowder. Your ears ring with screaming. The parallel universe collapses when your real students—in this universe—need to be picked up from art class. But the other universe never vanishes completely. Like a dead star, it forever sends signals. Sometimes the signals are faint pulses that lick the back of your mind. Other times they are flares that reach across the galaxy to fry every delicate circuit in your brain.

My school was built in 1922. Alongside each classroom door is a tall, narrow window, presumably to bring sunlight into the hallways. The flaw with such a design, in the Age of School Shootings, is glaring. Teachers are expected to cover these windows completely. Some use pretty stained-glass privacy paper. Others hang fabric. One teacher has a Red Sox curtain. My room’s previous teacher used puppy stickers. The puppies are cute but don’t cover the glass entirely. A killer in the hallway could peek between the pugs and golden retrievers. I hang a curtain as an added layer. But couldn’t a killer shoot the glass, reach in, and open my door? Stickers and curtains and faux stained glass won’t save us. Covering our hallway windows is perhaps meant to create the illusion of safety, like taking off shoes for airport security. Which I also appreciate. I do like feeling safe. Even if we’re not.

My classroom is at the end of a first-floor wing, 20 yards from the exit. My students can be outside in 30 seconds. When I consider our proximity to safety—especially in comparison to the fifth-grade classrooms upstairs—it makes me almost woozy with relief. But a door, any door, works both ways. Say the shooter were to gain entry at the end of our wing, then my classroom would be—

No. Stop worrying. Focus on teaching. I’m being paranoid. I must have some deeper anxiety choosing to manifest in this way. After all, from 2000 to 2021, shootings have only occurred at about 300 of our nation’s 88,925 pre-K, elementary, and middle schools. A kindhearted statistician, hoping to quell my anxiety, might represent this number as about 0.003 percent of these schools that have experienced a shooting. Those are very slim odds: 3 in 1,000.

Another statistician, however, might chime in to compare these odds against the odds of being struck by lightning (less than 1 in a million) or being killed by a shark (1 in 3,748,067), two dangers that will almost certainly never happen, yet that we worry about, and take precautions against, all the same.

District policy mandates that I lock my hallway door at all times, but there are two additional doors into my classroom: One opens into another fourth-grade classroom and another into a third-grade classroom. The third-grade teacher has the biceps and neck of a young guy who spends his summers lugging kegs for a beer distributor, which he does. It brought me great relief to have him as my neighbor. I imagined, play by play, scenarios in which we tackled a shooter. In some scenarios, I died. In others, the third-grade teacher died. Sometimes we both died, but so did the shooter, and our students were all safe. The third-grade teacher has since left to join the fire department. I never asked if he imagined similar scenarios where we try to save our students—it felt strangely intimate. But I suspect he did imagine those scenarios. I suspect the new third-grade teacher has as well. I suspect there isn’t a teacher in my wing, my school, America, who has not imagined, in terrible detail, exactly what they may one day have to do.

I INFORM MY KIDS of our first lockdown drill well ahead of time, posting it on our daily schedule after reading and before music. We review procedures during morning meeting. A fire drill is easy to explain to children. A lockdown drill is not.

“We need to be ready in case it’s too dangerous to go into the hallway,” I say.

Some of my students have parents or siblings who may have talked to them about school shootings. Many, however, are blissfully unaware. I have one student who still cries at every fire alarm. Most of my students write letters to Santa Claus. They are nine and ten years old. They are children. They cannot compute the idea that an adult would enter their school to murder them and Mr. Fuller and their friends. I’m not going to be the one to put this idea into their heads. Still, as the time for the lockdown drill approaches, they glance at the clock. They are nervous. I’m nervous. In 2017, shortly after Mexico City’s annual earthquake drill, a real earthquake hit. What were the odds? Less than lightning. Less than sharks. Greater than zero.

Lockdown. Lockdown. Lockdown.

My students crouch by their desks. I run into the hallway to look for stray kids in need of shelter. I double-check that the door is locked. I turn off lights. I lower blinds. I whip out the card I keep in my wallet for this sole occasion: my class roster. I whisper-call attendance. We wait together, but not together—spread apart, as instructed, to avoid being one easy target. The kids become restless, because they are kids. But they are doing great. I get teary eyed, watching them try so hard to be quiet and still. When this is over, I will remind them of just how great they are. I send a thumbs-up. Then I hear footsteps. The hallway door handle jiggles.

It’s the assistant principal, I tell myself. Or the police. Walking the hallways, checking that all doors are locked. Thanks to the puppy stickers and curtain, whoever is standing outside cannot see in, just like I can’t see out. The parallel universe has never been so close. This is the point of a drill, I remember. To feel as if the threat is real.

I glance at my windows. My plan of silently lowering 21 students to the ground is suddenly absurd. What if the shooter were outside? What if there were two shooters, like at Columbine?

The footsteps continue down the hallway. A few minutes later, the assistant principal’s voice comes over the loudspeaker. The drill is over. We are safe.

I WASN’T ALWAYS so consistently worried about school shootings. I wasn’t this permanently shaken after Sandy Hook, when I taught in New York, not far away. I don’t remember such a persistent feeling of dread after Parkland. Something has changed. Maybe it’s the cumulative effect of so many shootings. Maybe it’s entering middle age. Maybe it’s Uvalde, Texas, when nearly 400 armed law-enforcement officers stood outside Robb Elementary, working only to handcuff and pepper-spray parents who tried to stop the massacre.

September tilts into October. We have established a wonderful rhythm as a class. Some afternoons I say goodbye to my students and tidy up and prepare tomorrow’s morning message and change the schedule and prep the next reading lesson and put silly taco stickers on extra-credit math challenges, when suddenly I realize that the day has passed without one thought of a shooter murdering my students. I am very conflicted about these days. On one hand, I feel happily exhausted, like teachers probably used to feel before the Age of School Shootings. On the other hand, I feel like I’m getting lazy. Letting down my guard.

“You have a hammer on your desk,” a student informs me one morning. The student’s backpack hook is near my desk, giving him a behind-the-scenes peek at my cluttered workspace.

“You’re right,” I tell him. “For hanging art, and signs, and lights.”

I do, in fact, use my hammer often to hang art and signs and lights. I love decorating my classroom. But that’s not the only reason I keep a hammer near my desk.

HANDGUNS, SHOTGUNS, RIFLES. I’ve shot them all. My wife and I once fired an AR-15 at a gravel pit in central Maine. The sound was phenomenal, even with earmuffs. The allure of such power—such protection—is a strong potion. About half of all states allow districts to give permission for teachers to carry guns. Maine isn’t one of those states. Even if it were, I know better. The statistics are clear: People with guns—and those around them—face substantially higher risks of being killed themselves. Rationally, more guns equal more tragedy. Emotionally, however—

My previous school faced an awful pandemic decision: They had to spread out classes to maximize social distancing, but doing so meant putting the fourth grade into a gym on the main road. In exchange for fantastic ventilation (tall ceilings, big double doors) that kept us safer from Covid, we were far away from the school’s one security guard, with our doors literally open to whoever decided to walk off the road. And people did—usually workers with Amazon or UPS, looking for the main office, sometimes asking one of my students before me. I cannot adequately explain the depth of utter dread that an elementary school teacher feels at the unexpected sight of a strange man in the classroom.

This was when I began teaching in the way a Mafia don eats dinner out—orienting myself as often as possible to face the doors. This was the first time in my career that I started really counting down days until summer. This was when I began keeping a hammer in sight.

MID-NOVEMBER. I’m showing my students how to unpack tricky vocabulary in their nonfiction books when the loudspeaker comes alive with the principal’s voice:

Attention. We are entering a shelter-in-place. Please check your email and conduct business as usual until further notice.

The school literacy coach happens to be in my classroom. We say to each other with our eyes: The door. She is closer. She quickly pulls in a student from the hallway, then double-checks that the door is locked. My students are clustered on the rug with their reading materials. I am nauseous with adrenaline.

“What’s happening?” one asks.

“Is this a drill?” asks another.

“We’re just being safe,” I say. “We’re here together and we’re safe. Everything’s fine.”

I task the kids to search their books for unfamiliar words to add to their personal glossaries. While they search, the literacy coach and I check our emails:

Hello,

We just received word there is an active shooter in the Sanford area. We have been advised to go into a hold in place until further notice. This means you need to:

Continue teaching as normal

Close the blinds, shades, doors

Keep kids in your class—if there is an emergency and a student needs to use the bathroom please radio the office for an escort

We will notify you of more information once central office provides it

Sanford is a few towns over. Twenty-ish miles. As I close the blinds, the thought crosses my mind that the shooter called in the threat to Sanford to draw the police away from his real target: my school, my classroom, my students. The parallel universe is here.

I should tell the kids to scatter around the room.

No, I should tell them to pile behind my heavy steel desk.

No, I should—

I glance at my hammer.

I glance at the literacy coach.

We are acting as if everything is normal. So we continue the act. Ten minutes go by like this. Twenty. One boy announces they are missing PE. The class groans. I end the reading lesson and tell them to read, draw, or make another quiet choice. I check and recheck Twitter:

Forty minutes after her initial announcement, the principal returns to the loudspeaker. It was a false alarm, she explains, and a chance for us to practice our safety routines. We did a fantastic job. Now we can continue with our day.

My day includes writing, recess duty, math, science, dismissal, a staff meeting, then three hours of parent conferences.

At the staff meeting, we learn that ten hoax calls were made to ten school across Maine. We learn that parents had been lining up outside our school. We learn that four students peed themselves because they couldn’t leave their classrooms.

“It’s terrible,” the principal says about the accidents, “but better than a student being injured.”

It was important to the principal that only she and the assistant principal were escorting kids to bathrooms, she explained: “I would never ask a teacher to take that risk.”

We’re all talking around the idea. Nobody mouths the nouns or verbs that would center us to the tragedy that happened in the parallel universe, and now lives within each of us.

One teacher whispers, “It’s so scary,” and we all nod as though she has said, “Amen.”

The meeting ends. I don’t have time to process until well after parent conferences, walking that night with my wife. I choke up. Shake a little like a dog after a storm.

Nothing happened. It wasn’t real. But also it was.

TEACHING ELEMENTARY SCHOOL is acting. You act like an off-the-wall comment is insightful. You act like you didn’t hear that loud fart. You act like mild friend drama is the most serious conflict in the world. Acting is especially important the day after a school shooting. The day after a shooting, high school teachers can discuss with their students what happened, leave space for thoughts, concerns. Elementary school teachers cannot. I can’t let my students know that I’m scared for our lives. I can’t give an inch to the idea that their classroom isn’t the safest place on earth.

At my previous school, I had morning recess duty the day after the Uvalde shooting. I brought my trombone, as I would sometimes do. As students arrived, I played a few regal notes, announcing kids as if they were royalty. They either loved it or rolled their eyes. I was lightening the mood while keeping an eye out; faculty had been directed not to bring up the shooting unless a student did first, and even then, in private, to shelter other children from the news. I remember a similar directive after Sandy Hook. In both cases, not one student mentioned the shootings.

At my new school, the morning after the hoax calls, I overhear one student tell another that there were ten school shootings yesterday. I gently call him over. They were hoaxes, I explain. Hoax means fake. I tell him to stop spreading rumors. Because nothing bad happened. I ask him: How are you feeling? Are you worried? Want to talk?

I’m prepared to talk with children about this scariest thing. It’s worse to dismiss it or make them feel reprimanded for voicing it. But this student doesn’t want to talk.

I can sense that I’ve made him feel punished. I remind him that he’s safe in our classroom; I promise him that.

“I know,” he says.

I hate that this is our first interaction of the day.

I hate that we need to have this conversation at all.

I hate to offer my students a promise I can’t keep.

THE DAY BEFORE Thanksgiving break, I asked my students to reflect. What are we grateful for in our homes? Our town? Our planet?

Their responses were genuine and endearing: brothers and sisters, moms and dads, the beach, the ice cream shop on Main Street, puppies, oxygen.

I shared with them some of mine: my wife’s art and cooking, our local beaches and woods, water. My other gratitudes I kept to myself: our classroom’s proximity to the nearest exit. Our first-floor windows. The 56 days of school in which nobody has tried to kill us.

Elementary classroom teachers spend about six hours a day with their students, 180-ish days a year. I find it difficult—impossible?—to share this much time with a group of children and not come to love them deeply. I think of the bond as my evolutionary inheritance. The classroom is our village. I am the elder. My role is to teach. To raise and protect and send forth. My district mandates 175 school days in the year. I don’t like to be that teacher who counts down, but now I am. We’ve made it through the winter. Spring is here. So far we are doing great. We’re more than halfway there.

Nick Fuller Googins is a fourth-grade teacher and the author of the upcoming novel, The Great Transition. His writing has appeared in The Los Angeles Times, The Paris Review, The Sun, and elsewhere.

Comments are closed.