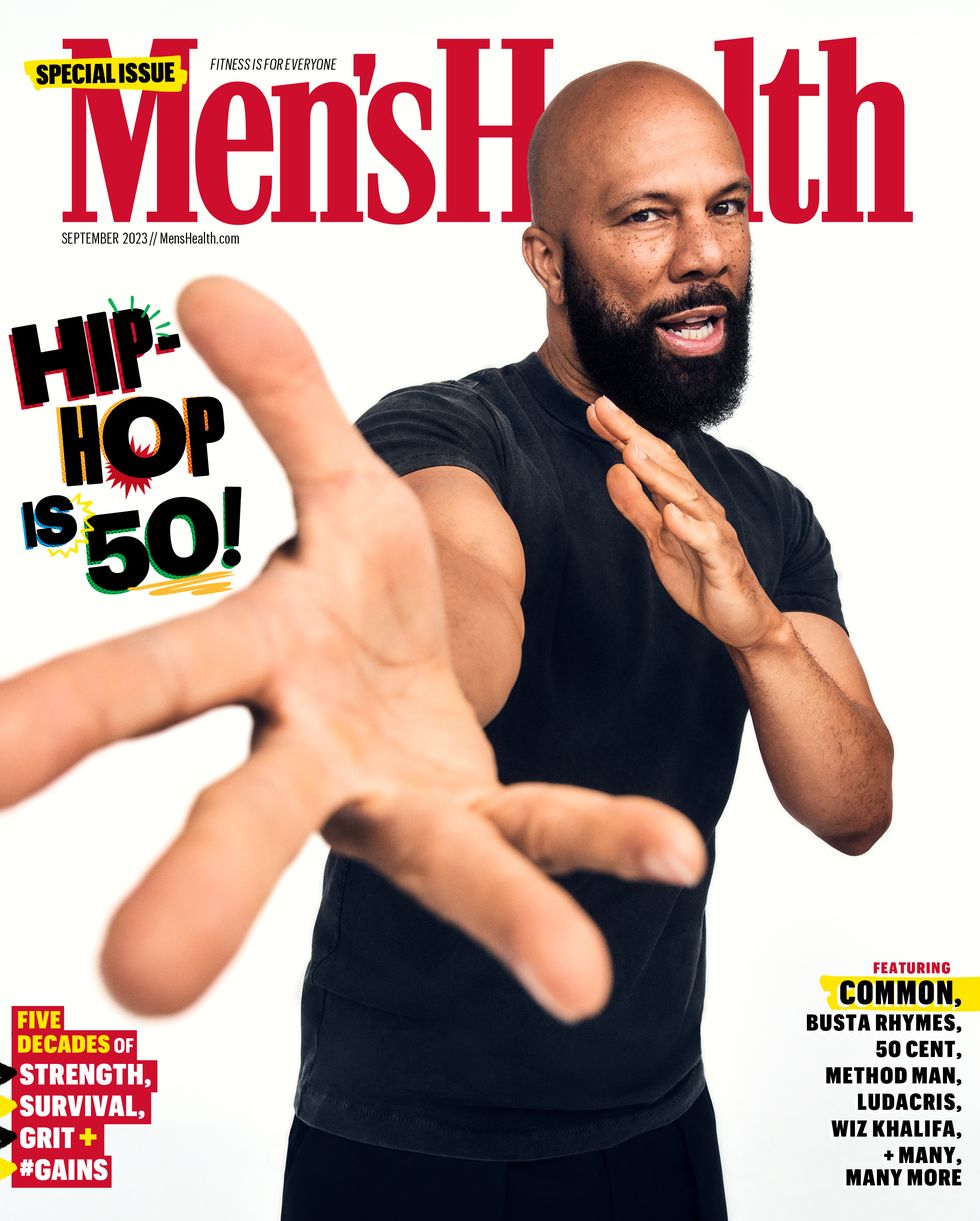

This cover story is part of Hip-Hop Is Life, a series of profiles and features that revisit key moments in the intersection of hip-hop and Black men’s health over the last 50 years. Read the rest of the stories here.

BEFORE 51-YEAR-OLD Common became a vegan and an Oscar- and Grammy Award–winning vessel for Black stories, he was just Lonnie Rashid Lynn growing up in Chicago without any guidance on how to eat healthy. He doesn’t remember anyone coming to the inner cities to give dietary insights. He couldn’t dream past the options given to him until 1988 when pioneering rapper KRS-One changed his life with one song, “My Philosophy.”

“To hear somebody who’s a hero of mine say, ‘No goat or ham or chicken or turkey or hamburger, cuz to me that’s suicide, self-murder’ was big.”

Although Common gave up pork and beef by 1996, he still struggled with alcoholism. (Which he chronicled on the track “Book of Life”: “My liver I burn it up…the cup I gotta give it up.”) He contends it played a central role in his music because “hip-hop is reflective of our communities, and one of the things that we have been dealing with in our communities—and I dealt with it, too—is alcoholism.” Initially, Common simply reflected the Black experience in his music; he didn’t influence behavior as KRS-One did for a young Lonnie.

A canceled trip to the abortion clinic changed all that and the course of his 30-plus-year career. He remembers when he and his partner, Kim Jones, were on the way to the abortion clinic to undergo their second abortion, but then the pair decided to have a child and try to figure out parenting. Common turned his revelatory conversations with Kim into a tender Lauryn Hill–assisted track, “Retrospect for Life,” from his 1997 album One Day It’ll All Make Sense. His thought process was laid bare—the financial and emotional insecurity, the guilt in taking a life, the pledge to “use self-control instead of birth control.”

The transparency was captivating, and sharing his decision-making process was instructive. After a performance one night, he remembers a fan letting him know it wasn’t just his story he was telling. “He said, ‘My lady and I were going back and forth about this, and then we listened to that song and just cried and said we were going to do this,’” Common remembers. “That moved my spirit in a way. That was a turning point for me in understanding how valuable just being truthful, telling my experiences, and also being really open about it can be.”

Since then, Common’s felt duty-bound to carry the weight of Black truths, even if it means unloading his secrets. In his 2019 memoir, Let Love Have the Last Word, and his Let Love EP, he bravely opened up about being molested by a family friend when he was a child. Not only did he hear about Black men opening up about similar experiences due to his honesty, but the hip-hop community also embraced his vulnerability in ways he doubted it would’ve back in the ’90s. “I don’t think we as a community in hip-hop, at the time, was as open to that type of vulnerability because the machismo was a lot of what hip-hop was about.”

While he loves the genre’s growth, he’s seen far too many hip-hop legends die without proper medical attention. He wants hip-hop to form a union to ensure that anyone who’s contributed to the culture is cared for by it. “That would be something in the next 50 years that I would really advocate for and fight for.”

Months before the SAG strike and in celebration of hip-hop’s 50th anniversary, the C-O double-M O-N reflected on the culture’s health journey, how unionizing can help save lives, and why he’s comfortable shouldering the weight of Black America, even if it means baring his darkest secrets.

Men’s Health: Hip-hop is turning 50 this year. How have you seen the culture’s discussion on health evolve over the years?

Common: Early on, hip-hop influenced and discussed health in a clever way. I can go directly to KRS-One’s song “My Philosophy,” which is one of the most influential songs on me as far as health. Growing up in Chicago, I just ate whatever I wanted and didn’t think about removing foods from my diet. So to hear somebody who’s a hero of mine say, “A vegetarian, no goat or ham or chicken or turkey or hamburger, cuz to me that’s suicide, self-murder” was big. Then he started doing songs about beef. I would also hear Rakim talk about eating fish a lot, and it was a health awareness that was really natural. I also think some of the brothers got that health awareness from being part of the Five-Percent Nation of Islam, and some of them just got it from just the consciousness that existed in the boroughs of New York and amongst people that were from the communities. That’s exceptional because, usually, in our neighborhoods, we are not introduced to health. You normally wouldn’t go to an inner-city neighborhood and hear people talking about eating certain foods or being healthy. Hip-hop did guide a lot of us who weren’t introduced to the concept of health and awareness.

I’ve seen it evolve as a lot more people are talking about mental health as part of the health conversation. Also, people are realizing that diet plays a part in diseases that we deal with. A lot of people are looking at health care and saying, “We need that, and we need to have access to that, and we need access to some of the wellness and holistic living, too.” As far as hip-hop, I do think one big gap that I wish I was smart enough—and we were more aware enough—to create was a union for people in hip-hop culture and musicians that could have established a way for us to have health care. Artists that participated and put out music and their careers may have gone a different way, but they’d still have health care. One of my great comrades and friends, J Dilla, was dealing with health issues. For me, to be a part of the [Screen Actors Guild] union and having health-care benefits and seeing what unions do for people’s health-care benefits makes me wish we would’ve done that for hip-hop. Maybe it can still be done.

Hip-hop is the voice of the voiceless, and you’re one of those people amplifying Black stories. Do you ever feel the weight of Black America and telling Black stories? Especially since you were still a young man figuring life out yourself.

I felt the weight, but it was a weight I wanted to carry because I knew that my people, Black America, were dealing with a lot of situations that had been pushed upon us. We are living in the midst of the struggles that have been the result of the dehumanization of Black people and the Black body. Knowing the historical trauma and struggles that we had been through and the hatred we had experienced, I felt like this weight of where we are now, where we were at that time when I was writing and still continue to write, it was my duty to speak to those truths and speak to the hope in it and speak to the understanding of what we have been through and are going through.

I also wanted to show I’m somebody out here just like you going through some of the same things. I’m making music, but I’m on this line with you, and I’ve experienced some of the same things. But I also understand we have to fight through it and get to the places of hope, and I’m part of the fight with you. So I tell my experiences with some of the ways how I’ve worked through these things. Or I might not have finished and worked through it, and I’m still dealing with it, but this is how I’m dealing with it. By relating to someone and sharing, it allows people to feel more open to where they are and also become more hopeful and maybe motivated because they notice someone is going through it.

That’s beautiful and is a great context for one of my favorite lyrics from you, which is on your song “Retrospect for Life,” when you say, “Imma use self-control instead of birth control cuz 315 dollars ain’t worth your soul.” You’ve said before that song helped someone decide to have a child, right?

I remember being at a performance and then walking outside of the show, and this dude came up to me, and he said, “Common, I really love your music. I want to tell you that your song ‘Retrospect for Life’ made me decide to have my kid. I wrote that song because I had been through that experience, and there was a moment when I was on the way to the abortion clinic, and the mother of my child decided, “We can’t do this again,” because this was after already having one abortion. Let’s figure out whatever we have to do. That situation showed when you receive experiences from a place of truth, it just resonates in a different way.

That’s why we related to when Nas talked about what he talked about on Illmatic. He experienced it, and the way he told it was just beautiful. In “One Love,” he talks to his boy in prison. That’s one of the greatest songs ever written. Recently, there was a dude at the play I did called Between Riverside and Crazy who was in a wheelchair. His mother was talking to me, and she said, “He’s so happy to meet you. He loves you, loved the play, and really loves your music.” A friend of his was dying, and he told him to listen to my music. That hit me in a different way because he told him to listen to it because it would give him some hope. His friend was leaving the planet, and my music was one of the things he was leaving his friend with to give him some hope.

How much of the change in your health came from knowing you were inspiring people?

I think it does affect how I move health-wise. But the first thing about health for me is taking care of myself first. As much as I want to influence and inspire, I have to make sure that I’m in my healthiest space. I’m not going to be vegan just so people out there know that I’m vegan and they could become vegan. I’m gonna do it initially as a choice for my life, but I’m going to share this because I want to inspire others to make choices for their lives that will be best for them and be healthy.

In your song “Time Travelin’” from Like Water for Chocolate, you rapped, “Stakes are high, like my uncle is / We both got problems, he never confronted his.” What issues were you talking about?

I had uncles that were dealing with drug addiction. One of my uncles died of AIDS. He had a drug addiction and was using needles. I loved my uncle Charles. He was one of the people that told me I could be something. My other uncle, Steve, was also dealing with some drug problems, and it was back and forth for him. I wrote about it because it was going on. I know many other people had people that were going through those things. It didn’t mean I loved them any less. I was just observing. He overcame it now. So to see him in the space where he says, “I’m not going over to this neighborhood because that’s where that trouble is for me,” just let me know it’s all in your choices.

That honesty about your family life reappeared years later when you opened up about being molested by a family friend as a child on your song “Memories of Home” on your Let Love EP. Do you think you would’ve been able to have that conversation about the molestation in hip-hop in the ’90s?

I don’t think I had the courage to. I could have had that conversation, but I don’t know how well it would’ve been accepted. For somebody to talk about being molested would be a record-scratch moment where everything’s stopping. People would say, “Why are you saying that? Why are you even talking about that?” But now I’ve had wives tell me their husbands have become better and more open because of that. It was something I hadn’t dealt with and had tucked away because of how we deal with trauma and difficult things like that. My defense mechanism was to act like it didn’t exist. I’ve met people who’ve been incarcerated and experienced those things, whose defense mechanism was to go out and be violent towards someone. The root of it was they had been sexually abused and physically abused.

To do that song and to write about that in my book was like, that’s where—what you talked about me doing something that’s like, okay, this is more about them than me at this point. It is liberating for me to talk about what I’ve been through and not be afraid to say it. When you just can acknowledge some of your pains, ills, and fears that you don’t feel like you could be attacked about it as much anymore. It becomes less of a vulnerable space when you really are dealing with those issues and are going through the process of healing from those issues. You become more powerful in it.

I felt more like myself since I’ve expressed those things than I ever have in my life. I was only able to meet myself where I was at that moment. But I got to that point and talked about being sexually molested, and it was like, “Wow, this is a whole ’nother thing.”

What do you see happening for hip-hop in the next 50 years, health-wise?

I would like to see us continue to be more open to the discussion of emotional, mental, and physical health and the promotion and expression of it. I want to see hip-hop culture creating spaces where people can do those things. When I saw Styles P and them open up that juice bar, I went to the opening and thought it was dope. To see hip-hop doing that. Seeing hip-hop continuing to talk about mental health and creating a union would still be something powerful that I would love to see us do because we could have access to that mental-health support, health and wellness support, and medical support when needed. That would be something in the next 50 years that I would really be an advocate for and fight for.

A version of this story appeared in the September 2023 issue of Men’s Health.

All shoots and interviews for this cover were conducted prior the SAG-AFTRA strike.

Senior Editor

Keith Nelson is a writer by fate and journalist by passion, who has connected dots to form the bigger picture for Men’s Health, Vibe Magazine, LEVEL MAG, REVOLT TV, Complex, Grammys.com, Red Bull, Okayplayer, and Mic, to name a few.

Comments are closed.