This story is part of Hip-Hop Is Life, a series of profiles and features that revisit key moments in the intersection of hip-hop and Black men’s health over the last 50 years. Read the rest of the stories here.

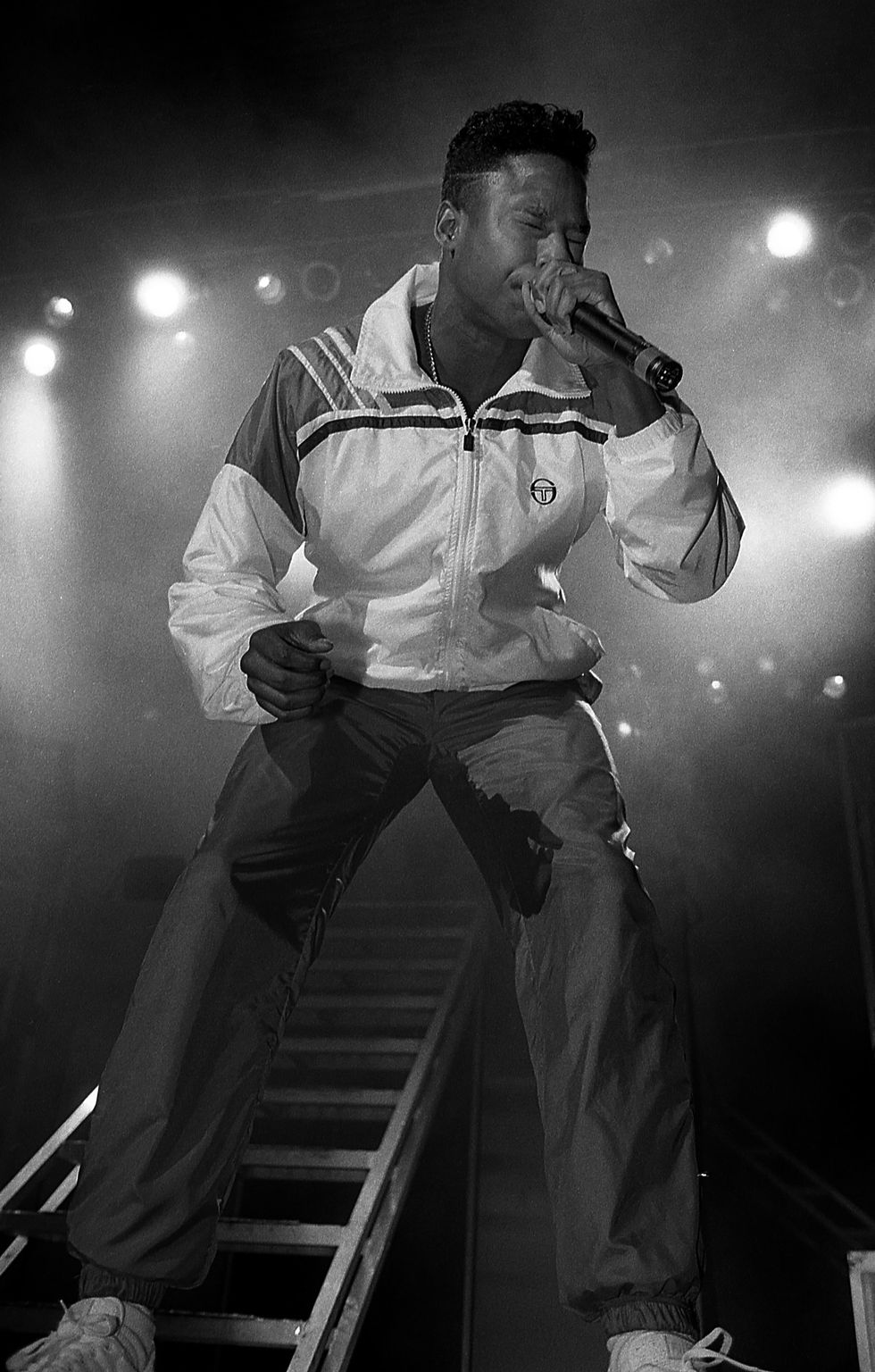

FOR MOST OF the 1980s, young Black males became victims of gun violence twice as often as white men in the same demographic. Hip-hop was shaken by this reality when 25-year-old DJ Scott La Rock of hip-hop group Boogie Down Productions (BDP) was gunned down in the same South Bronx neighborhood where hip-hop was born. A year later, Nassau Veterans Memorial Coliseum, a sports arena located in Long Island, banned rap concerts following the death of a 19-year-old Black male at a September 1988 concert featuring hip-hop pioneers Eric B. and Rakim and Doug E. Fresh. After this, hip-hop collectively as a culture had one response to the gun violence epidemic: Enough is enough.

La Rock’s Boogie Down Productions co-founder KRS-One channeled his sorrow into change by forming the Stop The Violence movement in 1988 to combat gun violence. The next year, he teamed up with music journalist Nelson George and Jive/RCA executive Ann Carli to gather the biggest rappers of the time and create the most popular anti-violence rap anthem to date titled, “Self Destruction.” MC Lyte, who contributed to the song, tells Men’s Health that its creation resulted from hip-hop leaders’ desire to “make a difference so we could possibly stop violence in our neighborhoods and all over the country.”

Doug E. Fresh, best known for indelible classics like “The Show” and “La Di Da Di,” remembers how necessary the song was for young Black men, including himself. “[In 1982], I performed at Savoy Manor, and a friend of mine got shot,” he says. “Nobody knew where he got shot; they just knew that the bullet hit him. I had to pull his body inside. It was a devastating thing because he was 18 years old. To this day, it’s fresh in my mind.”

This content is imported from youTube. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

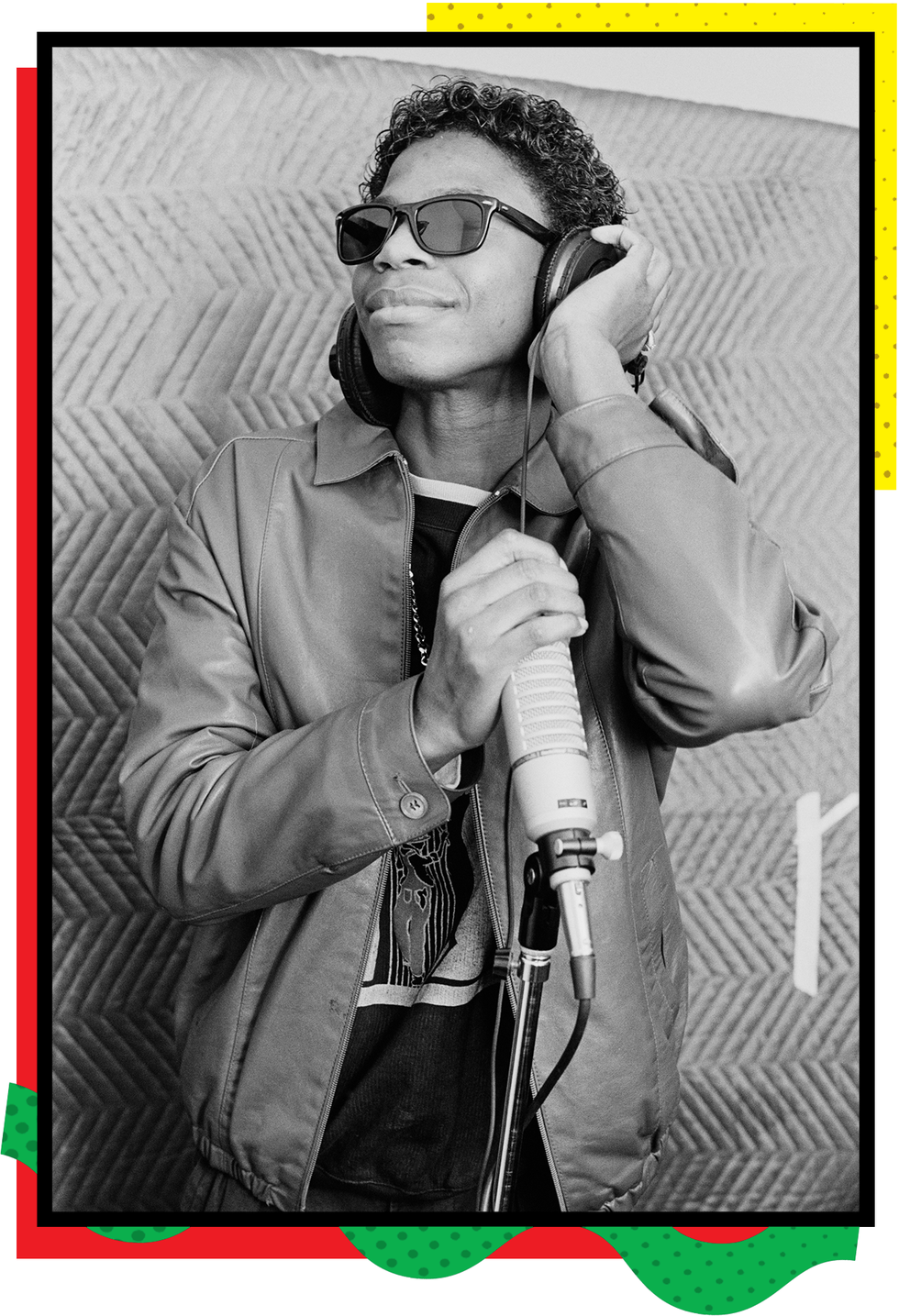

“Self Destruction” topped Billboard’s Hot Rap Songs Chart in March 1989, and the sales of the single and VHS tape of the music video raised over $100,000 for the National Urban League, which partnered with the Coalition to Stop Gun Violence. Forty years later, Doug E. Fresh is one of the “Self Destruction” disciples still fighting to keep Black men alive. His organization, Hip Hop Public Health, uses music and art to raise awareness about health issues facing Black people, similar to how “Self Destruction” put America on notice about the gun violence epidemic plaguing Black men.

Below, the 56-year-old philanthropist chats with Men’s Health about the gun violence epidemic that continues to disproportionately harm Black men today and how hip-hop has stood up to it through its lyrics and advocacy.

Men’s Health: How did the “Self Destruction” song come to fruition?

Doug E. Fresh: We were doing a lot of concerts, and there was a lot of violence. Cats [a slang term for “people”] were getting cut by razor blades, pulling guns out, or just beating [people] up. All the time, from the block parties to the jams, people would have different conflicts. We always tried to say, “Yo, calm down.” There was so much of that going on that we felt, collectively, it would be wise to use this power [of hip-hop to do something]. That was the beginning of the thought process. All of us collectively knew how important it was to get together and use our power to make [“Self Destruction”]. And it had a tremendous impact on hip-hop. “Self Destruction” made people more responsible.

In your verse on “Self Destruction,” you rap about a gold chain getting snatched. Was that a reference to the Nassau Coliseum show where someone got their chain snatched?

That was [something] that I’ve seen many people experience. Some people died for their gold chain. It was madness. It goes back to the mindset of how we were living, the way that we were thinking, the animalistic lifestyle where we’re running around killing people for a chain or a diamond watch. When I put my verse together, I put it together in real time. I just talked honestly about what I saw, what was happening, people dying, and how there was not enough love and unity when we went out.

Sometimes at these shows, guys look at it as an opportunity to resolve a problem with somebody because they know they would be there. A couple of guys would stir the whole energy into something crazy. Even the women would get wild. I remember this girl had some dude who tried to come at her, and he was talking crazy. She pulled out a little .22 and shot him in the ass [laughs]. That’s how crazy it was.

That’s why we took the position to change those conditions by using our name, our energy, and our power. Just recently, D-Nice got acknowledged at the Urban League for his contribution on Instagram Live [during the Covid lockdown]. I went to support him, and I was telling them, “We did this song ‘Self Destruction,’ and we gave all the proceeds to the Urban League.” So, it was interesting how everything turned around and came back [full circle].

Another inspiration for the song was the death of Scott La Rock. What do you remember about his death and how that impacted hip-hop?

It was shocking. I didn’t know Scott La Rock, but KRS-One told me that he and Scott La Rock would come to my shows around that time. Overall, we felt very sad. At the height of this young brother’s life, he’s getting ready to really pop off with KRS-One and BDP, and he loses his life. It was just one of those things that we wanted to prevent in hip-hop. Just like Takeoff, just like Jam Master Jay, we can go on and on.

How often did you hear about gun violence back then, and how did that affect your mental health?

You became numb to it because it was happening so consistently. Similar to the way [it is] now when you keep hearing about artist after artist dying. When one person died, it shocked you. Now that so many people are dying, it doesn’t shock you anymore. [Same with] police violence, like what we just saw on the news with the young brother [Tyre Nichols] getting beaten to death.

Did you feel like gun violence got worse throughout the ‘80s?

Gun violence got worse when people were getting more money. Everybody was wearing Tommy Hilfiger, and everybody started to go hard with the Gucci and Dapper Dan outfits, so people were trying to catch you even more. Before that, [though], there was still gun violence. This unstable mindset has been something that has been happening at hip-hop parties, go-go parties, and sometimes even dancehall. You put some alcohol in somebody; they got a knife, they got a gun, they see somebody they had a problem with, a lot of talking is going on. Before you know it, things are set off, and everybody’s trying to get out of there because they don’t want to get hurt. When guys are on drugs and drinking, it turns into a whole other vibe.

Crack cocaine hit Black communities hard in the ‘80s. Do you think the rise in gun violence and crack were intertwined?

It’s all intertwined. [Not just] people smoking crack, but the money people were making from crack was unbelievable. Then you got guys out there that were smoking dust. In the ‘80s, cats were sniffing cocaine. In the late ‘80s, that’s when crack came out. I made a song called “Nuthin'” on my debut album, which was about crack because it was so damaging. It hit on a level where the streets were just crazy. People were just so strung out. Crack was a different drug because dope had guys nodding off. Crack made you feel superhuman.

With songs like “Nuthin,'” did you feel like you had a responsibility to educate the listeners about their health, like the dangers of crack?

As an artist, I’ve always felt that it’s my responsibility to express what I’m learning and seeing around me. My records were about reality. The first generation of hip-hop was about rhyming about what you see; that’s why “The Message” is such a classic. The other style was braggadocious and based on escapism, being able to talk things into existence. Hip-hop artists have that ability. They have to be careful because what they speak into existence can destroy them or other people. I always felt I would use [my gift] to show you something or to uplift you.

What type of legacy do you hope “Self Destruction” leaves?

Hopefully, it lands in people’s spirits as a guide for other artists to follow and know what they can do together. They have so much power to change the conditions of this planet. [My team] kept coming to me saying, “Hey, y’all need to do a new ‘Self Destruction.’” That’s something that I’m looking at. “Self Destruction” planted the seed of putting all [of our] power together and using it for the greater good.

A version of this story appeared in the September 2023 issue of Men’s Health.

Comments are closed.