This story is part of Hip-Hop Is Life, a series of profiles and features that revisit key moments in the intersection of hip-hop and Black men’s health over the last 50 years. Read the rest of the stories here.

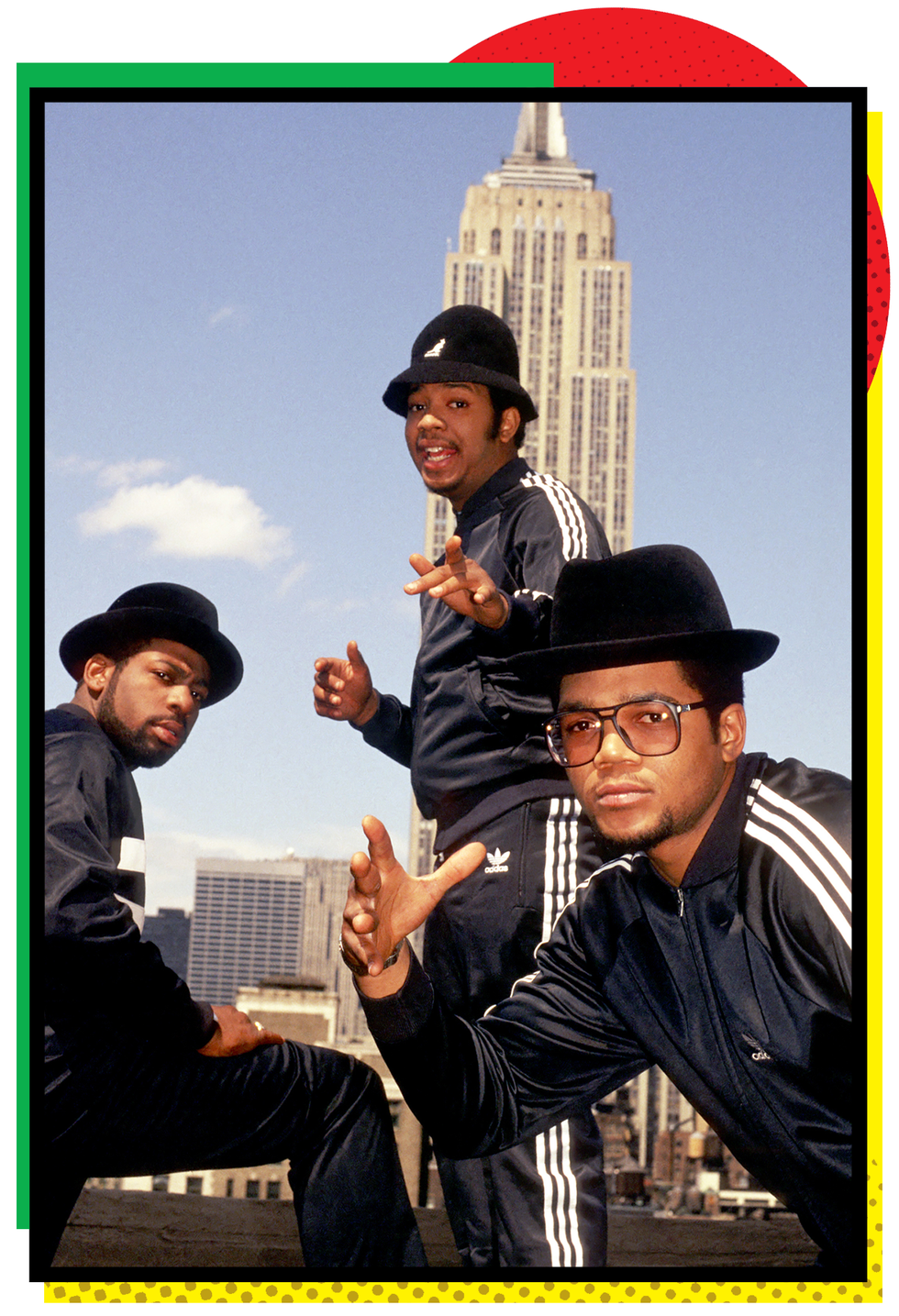

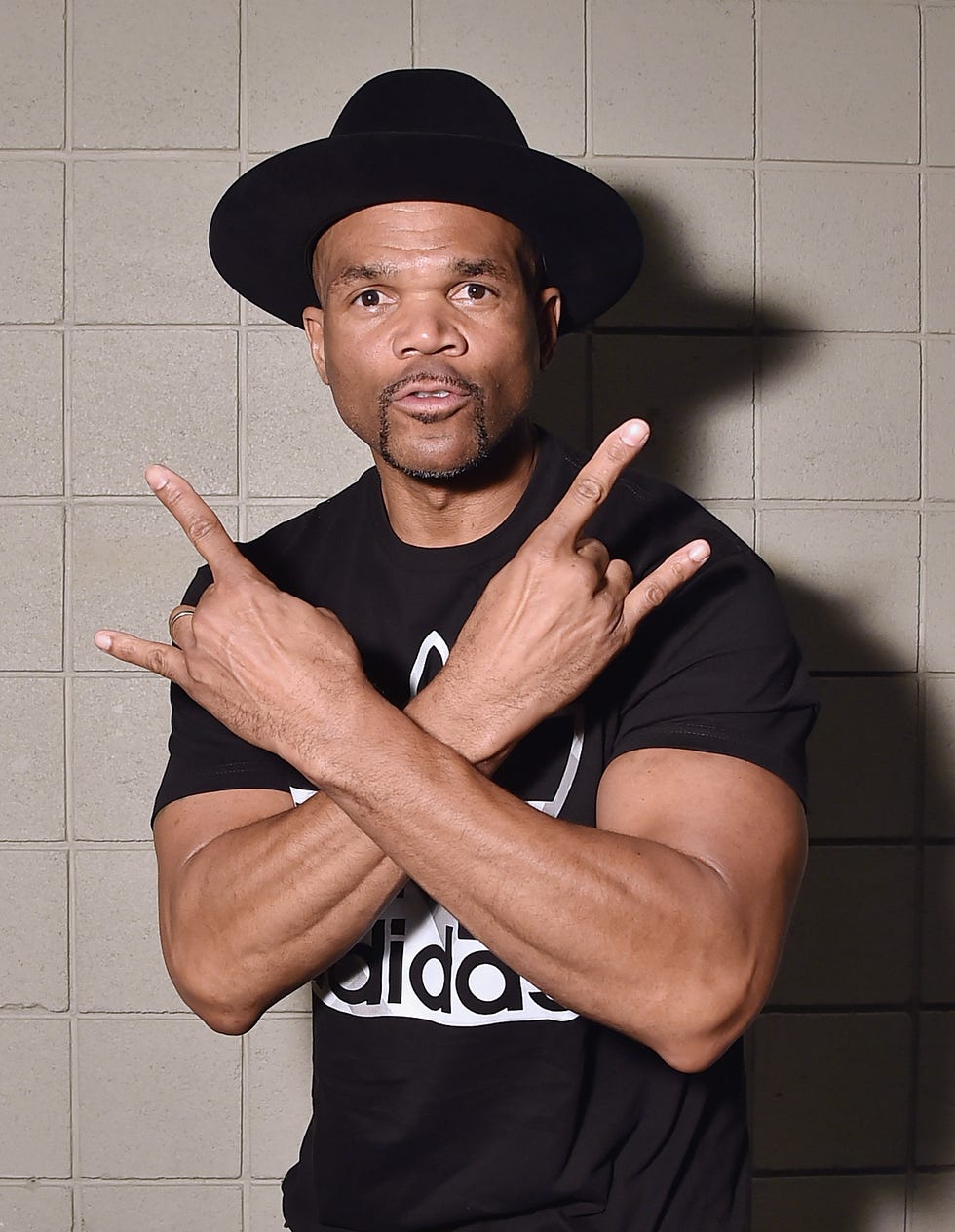

Darryl “DMC” McDaniels is a founding member of Run-DMC, one of the few hip-hop groups inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. Ahead, the 58-year-old rap legend shares his memories of how the genre helped people cope with the drug addiction, alcoholism, and poverty they were trying to escape at the parties in the Bronx where it all began.

IN NEW YORK City during the ‘70s, health wasn’t promoted. There weren’t any healthy food commercials. You wouldn’t see healthy foods on billboards. I grew up in Hollis, Queens, and there was always a liquor store, a fried fish market, and a Chinese food store with no healthy choices. Drugs were everywhere, and there was a lot of alcoholism. But, as young people, we generally were very healthy because we were always outside playing. There were no cell phones or video games. There were a lot of dope fiends nodding off on the street, but the dope fiends and drug addicts kept us healthy because we were running from them.

To get to the Bronx to see friends, I would have to leave my nice quiet block and walk up the same 25th street we immortalized as Run-DMC in the song “My Adidas” when we said “standing on two-fif street.” The Bronx was [like] Vietnam for those people living there—it was a war zone. When you went into the bodegas and grocery stores, the quality of everything sucked. I lived in Queens in the lowest suburban middle-class area, and we didn’t have [expired] potato chips and Devil Dogs like they did in the Bronx.

My earliest memory of hip-hop was in 1978 at St. Pascal Baylon Catholic School. I was in seventh grade, and this eighth grader came into the schoolyard with a tape recorder. He called my friends and I over to him, and one of my friends thought he wanted us to smoke cigarettes. It was common in the ‘hood for kids 12 and 13 years old to smoke Newports and Kools. We get over there, he pushes play on the tape, and the beat goes, boom-bap-boom-boom-boom-bap. Then, the voice goes, “When you mess around in New York town, you go down with the disco chiba clown. You go down, go down, go down, go down, go down.” We had never heard anything like this.

[There was no] recorded rap. Before “Rapper’s Delight,” [a song by The Sugarhill Gang] came out [in 1980], tapes were everything. People would go to the Bronx, Harlem, and Manhattan and tape the performances of guys like Grandmaster Flash, Funky 4 + 1, and the Treacherous Three. They would sell those tapes all around New York City. On some of these tapes, MCs would be shouting, “How many people out there smoke cocaine? If you sniff cocaine, let me hear you say blow.” The whole crowd would be like, “Blow!” The MC would say, “Say ‘I love cocaine,’” and the crowd would go, “I love cocaine.” Busy Bee Starski’s thing was asking, “Where do you eat at? Is it McDonald’s? Is it Burger King? How about Wendy’s?”

Hip-hop referenced things that were unhealthy because those things were part of our society’s lifestyle. If you were a little kid back then who loved rap, you may say, “Ok, I can DJ. I can rap. But, for me to be accepted, I need to get high.” Or you may think, “Everybody eats McDonald’s burgers. You must have to eat fries to survive.”

On “Rapper’s Delight,” Wonder Mike raps, “Have you ever went over to a friend’s house to eat and the food just ain’t no good? I mean, the macaroni’s soggy, the peas are mushed, and the chicken tastes like wood.” He talks about eating his friend’s fried chicken, and it’s the worst thing. If it was veggies and tomatoes and salads, we’d have been rapping about it. But, because it was part of our society and there were no alternatives, we didn’t rap about it.

Before I rapped, my first DJ name was Grandmaster Get High because my music was enough to get you intoxicated. You didn’t need Olde English. You didn’t need Wild Irish Rose. You didn’t need Bacardi. You didn’t need weed. My music is all you needed to intoxicate you. Getting high in New York City and the Black culture was a social thing of empowerment, recognition, and status. So, I told people they didn’t need any of that. But I wasn’t telling them from a healthy standpoint. I was bragging that my music was better than it all.

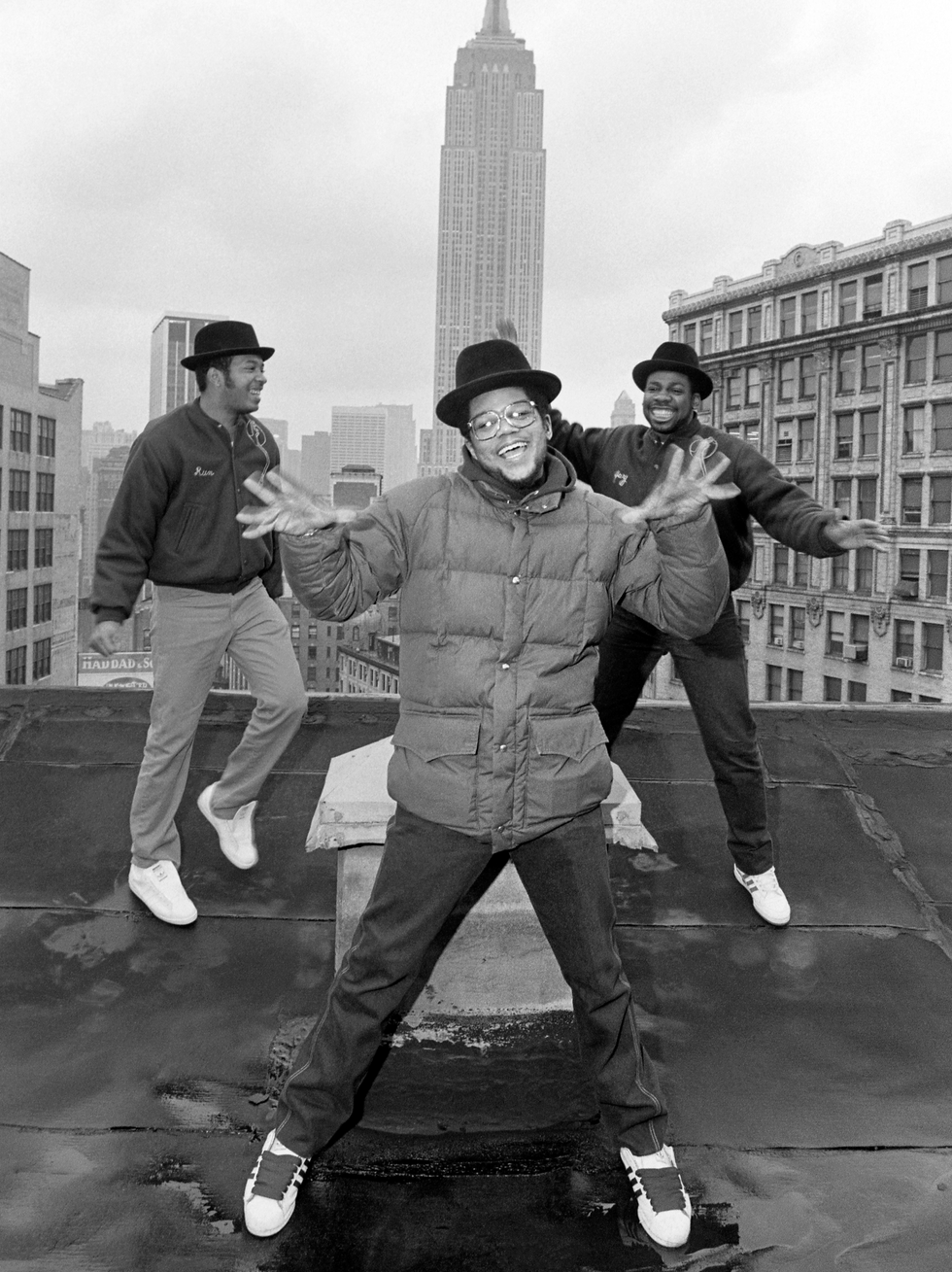

Another [memory] about hip-hop from the ’70s was that we went to parties and danced. We all sweated—even the killers and stick-up kids put their guns down. They got on the floor. It was those parties that kept us in shape. The greatest thing I remember from that time was a park jam in 1979 at Jamaica Park in Hollis, Queens, on 202nd Street. Even though we were eating unhealthy foods, the handball courts were full. The basketball courts were full. The kids were being active. Nobody was sitting around. The DJs were DJing. The park was packed. Life was going on.

It was all escapism. For two hours, we busted open a light pole, plugged up our turntables, and stole electricity from the city of New York just to play some music. There was no violence. We didn’t notice the death, destruction, and poverty around us for those two hours. It was heaven. You felt good emotionally, spiritually, and physically. It was a release from all the stress—physical, economic, and social—that we were going through. I’ll never forget that special time in hip-hop history.

Senior Editor

Keith Nelson is a writer by fate and journalist by passion, who has connected dots to form the bigger picture for Men’s Health, Vibe Magazine, LEVEL MAG, REVOLT TV, Complex, Grammys.com, Red Bull, Okayplayer, and Mic, to name a few.

Comments are closed.