Since 1973, hip-hop has been a megaphone for Black men. The mental health struggles, sexual awakenings, and aging revelations have been shared worldwide in its lyrics and advocacy. To celebrate hip-hop’s 50th anniversary and Black History Month, Men’s Health is exploring the culture’s past five decades by highlighting the moments and movements that reflected and influenced Black men’s health. To read the rest of the stories, click here.

HIP-HOP IS turning 50, but the culture hasn’t historically embraced rappers over age 35. From 1990 to 2010, only four rappers 35 or older reached #1 on the Billboard Hot 200 album chart: Eminem, Jay-Z, P. Diddy, and Common. Favoring the young while expelling the old kept the genre at the epicenter of cool but limited which Black men’s health stories got told. Black men may have been 16.6 percent of kidney failure patients in 2018, but those experiences were rarely spoken about by unaffected rappers in their 20s or older rappers silenced by ageism. That all began to change in the 2010s when the 20-year-old rappers of yesteryears grew up, and hip-hop began to embrace aging.

During this decade, rappers like Jermaine Dupri and Styles P began, respectively, promoting veganism in PETA ads and opening juice bars in New York City food deserts. Jay-Z sold millions of records extolling the virtues of eating turkey bacon and addressing his depression. Younger rappers like Logic and Mac Miller, who were influenced by the genre, even began scoring hits with songs that discussed previously taboo topics such as suicide prevention and self-care. Hip-hop made space for older rappers and healthier topics and, as a result, the 2010s became the first decade in hip-hop history where nine rappers over 35 reached #1 on the Billboard 200.

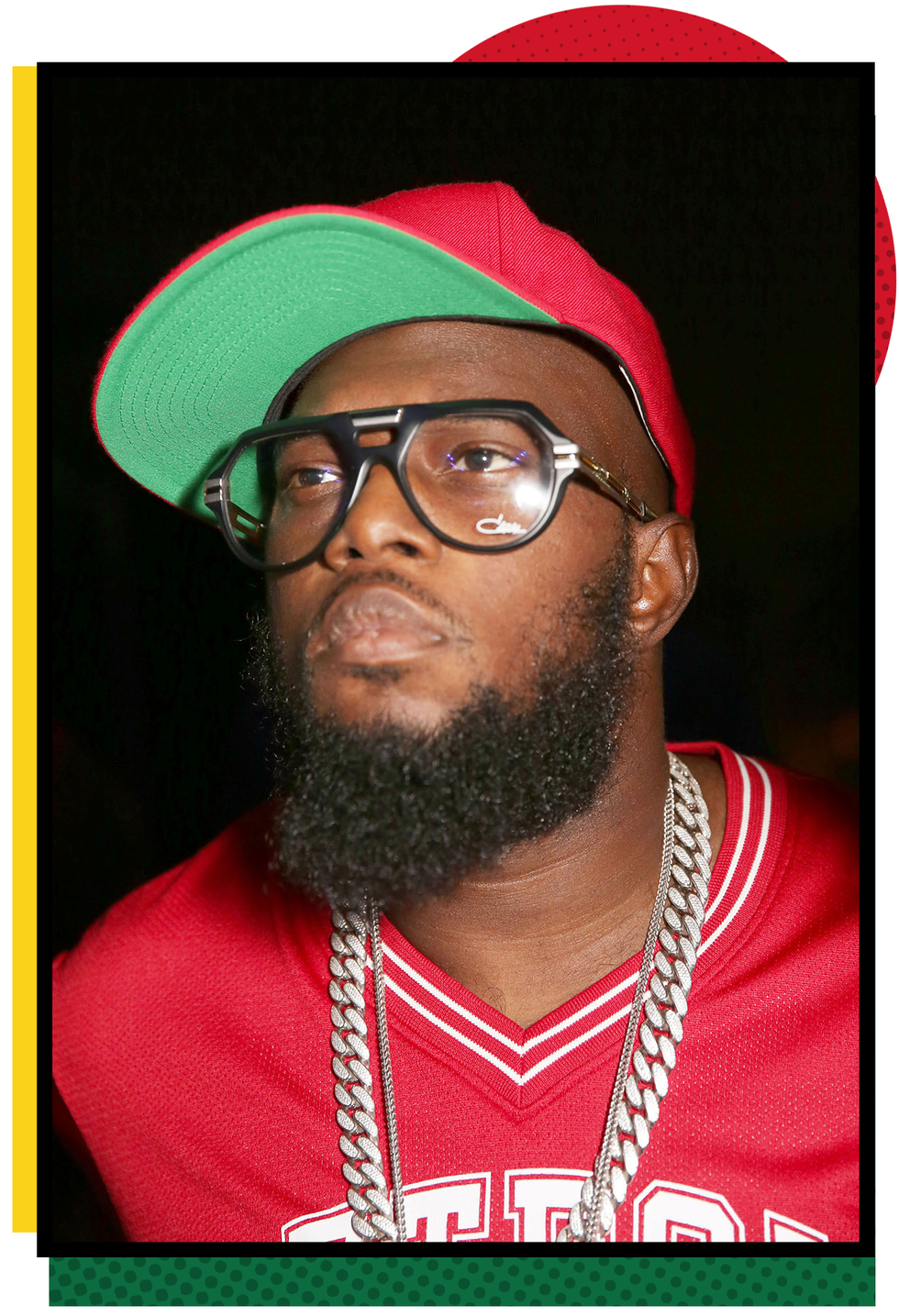

Leslie Pridgen, better known as the gravel-voiced, truth-telling rapper Freeway, used his story to help more Black men feel seen by hip-hop. After being signed to Jay-Z’s Roc-A-Fella Records in 2001 at age 23, reaching the Top 5 on the Billboard 200 at 24, and performing around the country before 30, he was diagnosed with diabetes in 2010 at age 32. Five years later, he found out he had chronic kidney disease and received a kidney transplant in 2019. His nights at the club were replaced with four-hour-long days of dialysis treatments three times per week. Still, you could find him opening up for Jay-Z and Beyoncé in New Jersey for their On The Run II Tour. Other Black men took note.

“I would be in a dialysis center and [post] on Instagram and Facebook. I was someone [my fans] could believe, trust, and actually see at the same time,” Freeway tells Men’s Health. “People had family members going through it. People themselves were going through it.”

Freeway is closer to his fans because of it. He showed them what a rapper after 35 looked like, and it looked like a lot of them, especially Black men. He can’t remember a day when someone doesn’t tell him how his perseverance inspired them, and he estimates nearly half of those people are Black men. His health journey resonates with the people he shares them with through the National Kidney Foundation, the Gift of Life organ donor organization, and his own Freedom Thinkers Academy because Freeway still means something. Hip-hop hasn’t forgotten him. Now 44, Freeway reflects on the decade when hip-hop began to grow up and embrace aging.

Men’s Health: You were 24 years old when your debut album, Philadelphia Freeway, came out in 2003. That was the same year Jay-Z retired for the first time at 33. What do you think about hip-hop’s relationship with age around the time you debuted? Do you feel there was space for rappers over 35 back then?

Freeway: I don’t think so. I think that’s one of the reasons why Jay was about to retire because it felt like you shouldn’t be rapping once you get older. I remember on my second album [in 2007], I did a song with Scarface [“Baby Don’t Do It”], and he said, “I don’t want to be another Joe, 55 doing concerts, relying on shows.” When that album came out, I was probably 29. I thought, “I’m definitely not trying to be a rapper at 40.” But I’m 44 now, and I still love it. I’m still going hard. I just feel like it’s something in hip-hop where they don’t respect the elders to the extent they should. But it’s been changing. Jay is 53, and Nas is 49, and they’re both doing their thing. It’s definitely switching a little bit, but back when I started, it definitely seemed like you shouldn’t be trying to rap when you are old.

Did you have a personal connection to any Black men who suffered from chronic kidney failure?

My uncle passed away last year, but [before that] he had a kidney transplant, and he had to go back on dialysis. He was diagnosed in 2010, five years before I was diagnosed. One day he was coming back from dialysis, and he fell, hit his head, and didn’t recover. I had that example in my family before he passed away. One of my first cousins, Shia, died because she had kidney issues and wasn’t taking care of herself.

You said in a 2019 interview that your life as a celebrity rapper made you feel as if you were invincible. Was there anything about that lifestyle you think contributed to your condition?

I feel as though my lifestyle as a recording artist definitely contributed to my diagnosis because I was moving around, going from city to city, and eating whatever I wanted. I’d be in the studio at two or three in the morning. We’d order cheeseburgers and pizza and stuff while we worked. I was living fast and not paying too much attention to my health and body.

Were there any other people in hip-hop who helped inspire some of your health choices in the 2010s?

When I was younger and first signed to [Roc-A-Fella Records], we used to be on tour with Jay and [Roc-A-Fella co-founder] Dame [Dash], and they were always on it. They would be in the gym in the morning. We would go out to eat, and they’d get baked chicken and crab cakes. They would tell us, “You better watch what you eat.” The message was always there, but we didn’t always embrace it. And those messages weren’t broadcasted [in the early 2000s]. I’m pretty sure if everybody knew Jay was in the gym working out and eating baked chicken, people probably would’ve tried to do it back then. Also, Dame Dash, who is one of my mentors, also had diabetes before I was diagnosed with kidney failure.

When Dame had diabetes, I would see him all the time taking his insulin and doing what he had to do. I would ask him, “What are you doing?” He would say, “Listen, I have diabetes. I’m taking my insulin because I have diabetes. There’s nothing to be ashamed of.” So, when I was diagnosed with diabetes, I knew there was nothing to be ashamed of because my OG Dame had diabetes, and he still was carrying it. That helped me with my decision as far as sharing what I was going through with everybody too.

After your diagnosis, you received a kidney transplant. How do you feel hip-hop embraced you then?

I feel like people embraced me, especially the people that care about me, and my fans. I was going through what so many Black men and Americans go through. That’s why I chose to stand in front of it instead of trying to keep it from people. When I came out with my diagnosis, you’d be surprised how many people in the music business were going through what I was going through. People that you would know were coming up to me saying, “I’m on dialysis, just don’t tell nobody. I do it three times a week.” It was something that affected a lot of people, and a lot of people were hiding from it. I felt that coming out with my story helped people be more comfortable with it. It also opened a lot of people’s eyes to it because I was diagnosed with end-stage renal failure. I was running around with three of the leading risk factors—hypertension, diabetes, and just being African-American.

Did any fans reach out to you to tell you how much your advocacy meant to them?

A lot of people did. It was almost every day. When it was going on, people would tell me, “You opened my eyes to this. You helped a family member of mine going through this.” Or they’d say, “I’m going through it, and I didn’t know how to handle it. Watching your journey helped me get through it.” I’m a Muslim, and it’s about helping people as much as possible and bringing awareness to important things. I feel like I’m doing my job as a Muslim also.

What’s your workout and diet like these days?

I make sure I do cardio at least five to six times a week. I try not to eat after six o’clock. I eat lean meat. I use portion control, where I don’t eat too much. I stay away from sugars. I stay away from salt and things that are not good for my body. Every now and then, I might drink a soda or something, but I try to drink a lot of water and other fluids. When I first got the new kidney, I was on a strict renal diet, but I’m now three years out. I just try my best every day.

Do you feel one of the responsibilities of getting older is helping future generations of Black men with their health choices?

That’s the responsibility of Black men in general. In Islam, we say, “Save yourself, then save your family, then save everyone else from the fire.” We start with ourselves, and when we get to a point where [if] we can help others, we try to help others. That’s what life is about.

Keith Nelson is a writer by fate and journalist by passion, who has connected dots to form the bigger picture for Men’s Health, Vibe Magazine, LEVEL MAG, REVOLT TV, Complex, Grammys.com, Red Bull, Okayplayer, and Mic, to name a few.

Comments are closed.