Clips Courtesy Beau Hightower

WHEN IT COMES to pain, there are two kinds of chiropractic patients. There are those who withdraw into themselves, becoming silent and tense as their therapist applies defibrillator-strength movements to their spinal joints. Then there are those who react. The mixed martial artist and model Michelle Waterson is the latter. “Ayeeeeeeee,” she cries out as chiropractor Beau Hightower deftly digs his thumbs into the muscles between her right shoulder and neck, straddling the strap of her lilac crop top with his fingers. Waterson delivers a long, pitiful mock wail.

Hightower, 39, smiles over his white-streaked black beard. It’s early March, and outside a strong wind slaps the side of the building. They’re in Hightower’s office on the second floor of the labyrinthine Jackson Wink MMA Academy in Albuquerque. Hightower is the director of sports medicine at Jackson Wink, and he also takes patients through the practice he founded in 2013, Elite Ortho-Therapy and Sports Medicine. This is one of five Elite-OSM offices, employing 13 therapists and four rehabilitation specialists in addition to Hightower: There are two other offices in Albuquerque, one in Las Vegas, and one in south Florida.

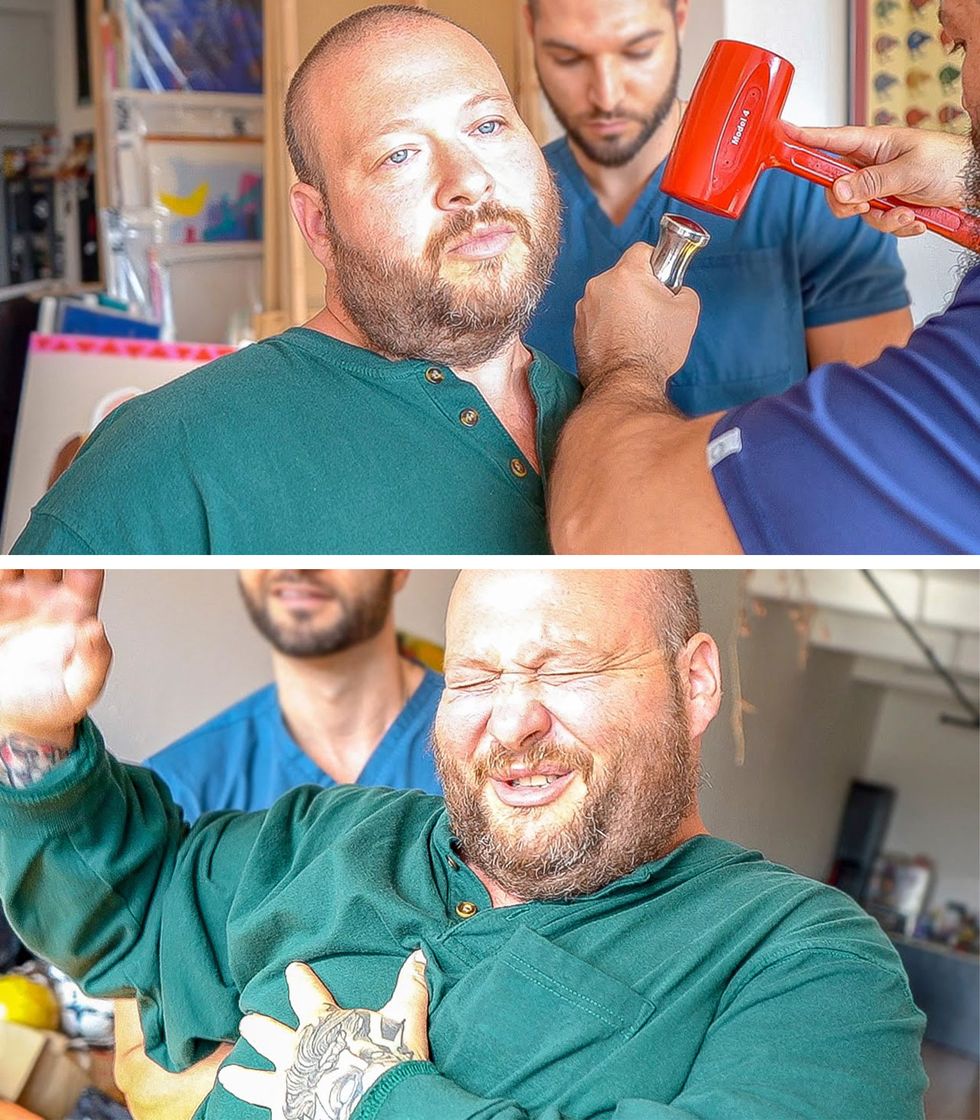

When Waterson arrived, they small-talked for ten minutes before Hightower’s wife, Brazilian model and fitness personality Lais DeLeon Hightower, holding a camera, lassoed their conversation with a pleasant but sharp “Let’s do this.” Hightower assumed a showman’s volume and intonation instantly. “What’s going on out there in YouTube land?” he asked loudly, like an old-school radio-show host, facing the camera and leaning over Waterson, who was laughing at the jarring switch-flip. He generally opens the show this way, with a sudden burst of schlocky animation, and in at least one instance he has leaped onto the table, going from a standing position to all fours with chimp-like agility, while delivering the greeting. “Today we’re back with one of our all-time favorite patients here: Michelle Waterson, the karate hottie.”

“Please be nice to me,” Waterson said. “I don’t want to cry today.”

Now she is seated on one of two padded tables, and Hightower is not being nice. The office is small, fluorescently lit, and not at all sleek, like a school nurse’s office. A three-foot-tall skeleton looks on from one window, and wrestling and MMA action figures, tensed for combat, chaperone the proceedings from a long shelf near the ceiling. Seven diplomas are clustered together on one wall; on another, Hightower has framed and hung his college football jersey as well as a Mensa certificate.

The casually clinical setting is the stage on which Hightower performs chiropractic adjustments on fighters, fitness models, fellow YouTube stars, and, increasingly, celebrities such as Ludacris and Action Bronson for millions of viewers. His YouTube channel, @DrBeauHightower, has more than 1.5 million subscribers, and the most watched videos on the channel boast 12 million views.

Waterson, who has been a patient for ten years, is a favorite guest not just of audiences but also of Hightower, both for her facial expressions (she once gazed up at him with a look of betrayal so pitiful that he dissolved into laughter) and for her general theatricality (“I told you to be gentle!”). The two talk amiably throughout her adjustment. At one point, she breezily describes accidentally popping a woman’s elbow out of place during a fight. “Is it better to just pop it back in right away?” she asks Hightower. “I can’t give specific medical advice on that,” he replies. While Hightower has a doctorate in “chiropractic”—the proper term for this discipline—from Parker University in Dallas and uses the honorific, he does not claim to be a medical doctor.

Only once during her adjustment does Waterson appear incapable of engagement. Hightower, kneading her right shoulder, instructs her to turn her head to the left and look over her shoulder. He often asks patients questions during adjustments, and now he wants to know what kind of music Waterson listens to. Waterson—stretching her head to the left, every muscle in her face wincing without disturbing her perfect eyeliner somehow—does not reply. Hightower tells her to turn her head back to him, then back to the left. She takes in and releases a deep breath. Finally, after 30 seconds, she answers: all kinds of music, but mostly country.

All the while, Hightower’s wife drifts around the room with the camera. Because the couple typically travel together anyway, she is Hightower’s de facto cameraperson. Before Waterson’s appointment began, DeLeon Hightower had said she was “not very good” at filming, but she moves confidently and steadily, always perfectly positioned to capture the higher-drama moments of the adjustment. There is nothing casual-clinical about DeLeon Hightower. While her husband wears a black scrubs-like top and bottom with orange-and-yellow sneakers, she appears camera-ready but for her Ugg slippers. She’s wearing matching brown Lululemon separates and looks impossibly dewy and fresh-faced—especially given Albuquerque’s parched air. She and Hightower have just returned from receiving stem-cell therapy in Colombia—face and scalp treatments for her, joint treatments for him—and her skin is as strong a testimonial for stem-cell procedures as I need. (As influencers, the couple received these treatments for free, which they recommend because stem-cell therapy is quite expensive.)

Now Hightower instructs Waterson to lie on the table on her back. He stands, then kneels, behind her head, hands on either side of her neck. DeLeon Hightower swoops in close on Waterson’s face. This will be one of the most replayed moments in the eventual YouTube video. Hightower, very focused, pauses, building anticipation for what’s to come. Then his hands move, rattlesnake quick, and the spectacle that draws millions of viewers to every video arrives: a multipart crack, each subsequent sound as satisfying as a jump from a skipped stone.

THOSE WHO UNDERSTAND joint cracks as metaphysical gifts from our bodies may be disappointed by the scientific explanation for a crack: It is a chemical reaction in which some of the liquid in the joints between bones becomes a gas, forming a nitrogen bubble. This reaction is caused by a strong mechanical force—for instance, the sudden motion of Hightower’s hands. When you crack your back on a foam roller, you’re experiencing a bunch of tiny “explosions.”

The sound you hear, explains Lisa DeStefano, D.O., the chair of Michigan State University College of Osteopathic Medicine’s department of osteopathic manipulative medicine, is actually not the sound of that chemical reaction occurring. “It’s the negative force,” she says. “It’s like”—she makes a clucking sound with her tongue—“we can cluck, right? And the reason why we cluck is because we’re causing a negative force to occur on the roof of our mouth. The noise is more or less that negative force mechanically releasing.”

Not everyone enjoys that sound. University of Alberta professor Gregory Kawchuk, D.C., Ph.D., who was clinically trained as a chiropractor before getting a doctorate in bioengineering, coauthored a seminal study in 2015 that used an MRI to show a crack in progress. Afterward, many readers who had always wondered about the mechanics of a crack contacted Kawchuk and his coauthors. “People sent me musical compositions they do with knuckles that have different notes, and they would crack them in order and play songs,” Kawchuk recalls. “It was this crazy time when people had these incredible stories about this thing that is really divisive. For some people, it’s: I enjoy it. It gives me relief. And other people cannot stand to hear it and they run away covering their ears.” He heard from people who had ended relationships because their partners cracked their joints all the time.

But for anyone who enjoys the sound and the sensation of receiving an adjustment, it can be addictive. Dr. DeStefano attributes this in part to the endorphins created by manipulation. When someone is applying pressure to a joint, she points out, it is very difficult to relax. “You’re anticipating this very quick, very small, high-velocity reaction from the clinician that you’re going to respond to in some way”—by relaxing, hopefully. There is tremendous expectation in those moments before a crack comes, “when they’re adding that force and adding it slowly and getting it right to that sweet spot where all they have to do is a teeny little nudge where everything goes blahhhhhh.” The autonomic nervous system is fully activated as it awaits a response. Once that response occurs, the body experiences a moment of shock.

If this explanation brings orgasms (their own genre of explosion) to mind, that’s allowed. The autonomic nervous system regulates the body’s involuntary processes, which include sexual arousal. And in fact it can feel slightly erotic watching someone have an involuntary audible reaction to a process occurring under the skin; some video subjects’ reactions seem almost comically pornographic. I shudder to think of the world hearing the noise I make when my boyfriend cracks my back by hoisting me up in a bear hug. (As with every movement described in this story, I discourage “trying this at home.” My boyfriend and I have tapered our home practice since learning from Dr. DeStefano that it’s not uncommon for people to have strokes following amateur adjustments.)

Subjects’ spectacular reactions likely have a lot to do with why it can be so satisfying to watch another person receive an adjustment. Viewers of Hightower’s videos seem to share in the anticipation of adjustments. Once, he made a video in which he cut away before each crack as an experiment. It was the most unliked video on the channel. Viewers like to hear the crack, and they like to see a patient reacting to it.

“Clinically speaking, it doesn’t necessarily matter how loud it is,” Hightower says of a crack. But he adds that he’d be lying if he denied that his and DeLeon Hightower’s eyes light up whenever a patient experiences a really loud one. “And a good patient reaction, too. Oh my gosh, what was that?” he mimes. “Oh my gosh, I felt that all the way down.” There is a universality to how patients respond after a nice loud crack, though it’s unclear whether it’s because the sensation hits them all in the same way, causing the same descriptors to leap to mind, or because many of Hightower’s patients have just watched a lot of his videos.

When I receive an adjustment from him, he asks me to put my hands behind my head, then stands behind me, loops his arms through mine, and yanks me upward. “I felt that all the way down my spine,” I say unprompted.

PATIENTS LIKE WATERSON who vocalize and make facial expressions during adjustments might seem less stoic or pain tolerant than the silent patients. But whether you emote or not just depends on how you react to being, as Dr. DeStefano puts it, “in an extreme state of vulnerability.”

I, for instance, find it impossible to make any sound at all during my own adjustment. I place my recorder next to me, hoping to continue interviewing Hightower while he works. He begins with my left shoulder, which is noticeably higher than the other, immediately zeroing in on a small orb of tension near my shoulder blade. Though Hightower can appear almost manic on camera during lulls, during the adjustments he’s focused and silent, staring ahead without blinking as he works by feel. He is not an exceptionally big man—some of his athlete clients tower over him—but his arms have a compact s trength that he can deploy explosively. Now he digs hard into the matter between my shoulder and my neck, and I trail off mid-sentence. The orb moves back and forth painfully under his thumb, until suddenly it is gone, reminiscent of one of those TikTok videos of storm-drain blockages being cleared. My recording comprises several minutes of Hightower chatting cheerfully as I occasionally exhale a “yep.”

Hightower does have silent patients but says he likely wouldn’t share videos of them. Likewise, he doesn’t share videos that make his clients look bad; he wants them to feel better, to return, and, ideally, to recommend him to their celebrity friends. He prefers doing videos with celebrities partly, he says, because public figures are more accustomed to the brutality of the Internet. “If the comment section decides they don’t like your clothes or the way you look, the average person isn’t used to having a million people commenting on their looks or their feet,” he says. He personally is no longer taking new, noncelebrity patients, though the other therapists at Elite-OSM are.

During adjustments, Hightower does interview his patients in a sense, but he specifies that he avoids “gotcha” questions. (He chats with them off camera, too, more because his sessions are long than because he wants to distract them from the adjustment. But the offscreen conversations are more natural and barbershop-like; he would not, he says, grill a patient about their favorite movies if he weren’t filming.) “Some of the MMA media is always trying to get a quote to cause conflict. That’s the nature of the media beast. But for us, that’s not what we want to do,” he says. If a patient feels vilified, Hightower tries to humanize them; if a patient has something to promote, Hightower folds it into his chatter, sometimes a little clumsily. “If we don’t have those relationships, we don’t have the next video.”

Hightower is far from a chiropractic version of Howard Stern. His questions aren’t only anti-“gotcha” but anodyne; still, it’s compelling to watch celebrities attempt to answer softball questions while they are in an extreme state of vulnerability. He compares the effect to that of Hot Ones, the show hosted by Sean Evans that features celebrity guests eating increasingly hot chicken wings while they answer questions.

Chiropractic videos also offer an unusual intimacy. “The movements sometimes involved, when you see them, can look quite unique. Because you just don’t see someone’s body usually moved that way in normal, everyday life—you have to be trained to do this, of course—then suddenly there’s this big sound,” Kawchuk says. “I think it’s a little along the lines of seeing what it looked like on an MRI. You can’t have that third-person, voyeuristic look at it when you get it done yourself. And usually these things are not done in public, so to see someone in a clinical setting is probably something new to a lot of people.”

Hightower understands the ASMR-like appeal of his work, and that the voyeuristic thrill can easily veer into something less tasteful. (“Massage table” is its own pornographic genre.) Viewers are most likely to click on videos of heavily muscled men, or women “that have certain curves or whatever to them,” he says. “We want them to be clickable, but we also don’t want them to get demonetized or be unprofessional.” So far, he seems to know exactly how far to push.

HIGHTOWER STUMBLED INTO YouTube fame. A little more than a decade ago, after he graduated from chiropractic school, he began working at a national clinic that specializes in acute pain and muscle and joint injuries. (It is very anti-crack, instead using chiefly soft-tissue manipulation.) He joined the company in Dallas and then switched into a more corporate role in Ohio. In 2012, he moved to Albuquerque, where his family lives and where, helpfully, Jackson Wink was a major MMA destination. Hightower already had experience working with UFC champions at the previous clinic, so the facility hired him. Initially, he wasn’t doing chiropractic adjustments, but then several fighters from Europe asked for them.

“We just happened to film it on Instagram. And we put it up on there, and it got like 800,000 views,” Hightower recalls. “So we did it again. Same thing. It was like a million views. So that’s when we knew there was something happening here.” This was about seven years ago, when chiropractic communities were beginning to form on YouTube. “You have what they call ‘crack addicts’—the people that are just addicted to all these crack channels. And you have MMA fighters. So it was like two overlapping audiences.”

The genre has earned a loyal following since then, and Hightower’s presence has grown wildly on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, and YouTube. On the wall kitty-corner t o Hightower’s diplomas are several plaques commemorating major YouTube milestones. Along the way, he has become a scholar of the Internet, building his audience by collaborating with other YouTubers. (He tends to cross over well with “gun tubers,” he says.) “YouTube is its own animal. You have to get a title and a thumbnail, and your timing has to be right.”

Hightower’s titles are often in all caps and deploy superlatives whenever possible—e.g., “The Most *LUDACRIS* Chiropractic Adjustments EVER?” and “I CRACKED EVERY BONE IN MY WIFE’S BODY,” one of his most popular videos, featuring DeLeon Hightower—and his thumbnail images, sometimes pantomimed at the end of appointments, frequently show patients mid-crack, mouths agape and eyes wide, panic giving way to satisfaction. The YouTube installments, often about 45 minutes, are long even compared with many contemporary TV shows. But with YouTube’s “most replayed” feature, in which a video’s highlights are visible when you hover over the progress bar below each one, viewers can navigate right to the climactic cracks.

Audiences also appear enchanted by a clownish-looking oversize mallet and wedge Hightower uses at intervals. This set of hammer massage tools is traditionally called a Tok-Sen, he explains. “It can loosen muscles. If we’re going quickly with it, it can trick the muscle into thinking it’s longer or shorter than it is, kind of like a vibrational gun.” He adapted the technique from Eastern practitioners, he says—the tools are not usually bright red in Eastern medicine—and honed it with instruction from a medical doctor from Holland.

More spectacular elements aside, h is channel has grown exponentially, in part because of well-cast patients—the occasional A-lister, sure, but also god-tier crackees such as Waterson. Any salacity is typically mitigated by DeLeon Hightower’s presence (female guests are subject to her approval), and Hightower tries to include significant others in videos whenever possible, even if the titles (“HAMMERED?! Geo gets INTENSE BODYWORK while HUSBAND WATCHES”) get cheeky sometimes. But audience behavior is distilled in the “most replayed” moments. When the subject of a video is a man, these moments almost always indicate satisfying cracks. When the subject is a woman, the moments generally include cracks but also the random compromising angle that might slip into a video. Hightower sometimes receives criticism for supposedly featuring women only in his videos, which he regards as a reflection of the critics’ viewing preferences: He says men actually account for 61 percent of his guests.

He has noticed that whereas at the dawn of the crack-video genre, “you could post anything and it’d get a million views,” he now has to be more strategic. He sees that his competitors’ traffic is no longer booming, and because he and his fellow YouTube chiropractors have historically grown their channels by piggybacking off one another’s traffic, he wonders how this will affect his growth. But he is serene about the future of the channel. “You have to look at these topics almost like TV shows, with a five- or six-year run,” he says. He has become meticulous about how often he posts, and makes sure that what he posts is worth posting, but he recognizes that the tides of the Internet are sometimes out of his control. “At the end of the day, these channels are entertainment. At some point, people get bored. The algorithm doesn’t like you anymore.” If that time comes, Hightower will still have Elite-OSM. Though surely his channel has helped him expand Elite-OSM by virtue of expanding his personal brand, he keeps the business distinct from his work on YouTube. The only nod to his videos on the Elite-OSM website is a recent ad he filmed for Volvo to promote the company’s new steering technology, in which he did adjustments on a group of truck drivers. It’s as if he’s protecting the business from the capriciousness of the Internet.

WHEN MY OWN adjustment is over, Hightower looks at me eagerly, his eyes bright and his brows raised, nodding slightly as if to say, “Right?” His conviction is contagious: Later I stand between two mirrors in my hotel room, studying my shoulders, and decide that they really do appear more level. Whenever Hightower begins to sound too mercenary about his videos, he seems to consciously shift in a more Hippocratic direction. After he acknowledges the thrill of good patient reactions, for instance, he pauses. “Of course, I got into this job because I want to help people,” he says. “When that reaction leaves them saying, ‘I feel so much better, wow’ or ‘My [father-in-law] is able to move his arm again’ ”—Hightower worked on Waterson’s father-in-law after a car accident left him partially paralyzed—“that’s why I do this job. The main thing is to make people’s lives a little bit better.”

The tension of making entertainment out of a medical (or medical-ish) process is omnipresent. In some ways, chiropractic was ripe for this type of treatment, just as dermatology was ripe for Dr. Pimple Popper to lance the field wide open for the disgust and pleasure of a massive audience. An adjustment yields results that are very visceral in the moment, much like the removal of a decade-old boil. And the ailments that patients arrive with, such as neck and lower-back pain, are universal and survivable.

Houston chiropractor Gregory E. Johnson is typically credited with the genre’s genesis. After his son suggested that he make videos, he says, Johnson published his first on YouTube on January 1, 2013. Johnson is known for his slightly nasal accent and his trademark move, the “Ring Dinger,” which involves raising the patient’s legs to flatten the arch of their back, fixing their pelvis in place with large padded pins, wrapping a towel around their neck, and pulling in such a way that the patient experiences cracks from head to hip. “Most of the chiro channels have a finishing move that helps them stand apart from the regular crackers,” Hightower says, laughing briefly. “Gregory Johnson has his Ring Dinger, and then there’s a Y-strap, there’s a magic hug, and there’s the guy with a hammer. It’s kind of like a video game, where every character has their specific special move.”

“It’s the realest deal I’ve felt,” said rapper Jack Harlow after his first Ring Dinger in September. The Ring Dinger notwithstanding, Johnson is relatively low theatrics. Most of his patients are civilians; his YouTube channel is simply called @AdvancedChiropracticRelief, the name of his practice, and has 525,000 subscribers. “We show raw patient experience from the time they walk in the door to the time they leave the adjustment,” he says. “We don’t edit any of our videos.”

Johnson says that since he began making videos, he’s noticed a shift in the attitude toward chiropractors, which has surely been catalyzed by videos like Hightower’s. Those who grew up saturated with chiropractic horror stories may reevaluate after witnessing adjustments on a parade of athletes, who have so much to lose in handing over their bodies to any professional, and other celebrities (though in my experience, actors in particular hold some very witchy beliefs about medicine). Criticisms of Johnson’s videos, which he says were “hot and heavy back in 2015” especially, have dropped off in recent years.

The risks remain, and it can be difficult to tell a bad chiropractor from a good chiropractor. Dr. DeStefano explains that there are manipulation no-no’s that laypeople wouldn’t necessarily recognize, such as simultaneous extension and rotation of the neck—this can stretch the inner lining of an artery so much that the blood can clot, and the clot can then travel to the brain. Being able to relax enough to let someone manipulate your joints requires tremendous trust, she adds. “They’re totally vulnerable to the hand of the person that’s doing the manipulation.” Having watched a hundred of Hightower’s videos, I felt, when he cracked my own back, that statistically I was likely to live.

Hightower is quick to point out that his track record shouldn’t inspire blithe confidence in the profession writ large. On the flip side, “you wouldn’t judge every neurosurgeon by Dr. Death,” he says, referring to the Texas spinal surgeon Christopher Duntsch, who famously maimed or killed more than 30 patients. But Hightower seems acutely aware of the influence of chiropractic’s bad actors on public opinion. Although he does use the title chiropractor, he primarily trains and hires naprapaths—practitioners who focus on a broader area of tissues than those surrounding the spine, the chiropractor’s chief purview. (In addition to his doctorate in chiropractic, he has a naprapathic doctorate from the Southwest University of Naprapathic Medicine in Santa Fe.) Hightower draws a sharp distinction between the two, as in one video titled “WHY I LEFT CHIROPRACTIC (What Is Naprapathic Medicine?),” but to a layperson the practices appear quite similar.

In contrast to more sensational chiropractors making adjustment videos—a friend directed me to one in which a chiropractor claimed to have restored a child’s hearing—Hightower keeps it simple. “I think we’re wired for that as humans, that there’s somebody out there who can heal the blind with their hands,” he says, and there are doctors who can work internal miracles. “But it’s not chiropractors, or naprapaths.” Chiropractic treatment alone is unlikely to indefinitely solve an underlying issue of pain (or any of the conditions tied to a loss of vision or hearing), and a significant criticism the practice’s detractors offer is that it is built around patients returning for treatment permanently. However, chiropractic can mitigate chronic pain in patients’ backs, necks, and shoulders, Hightower says. “Which is not nothing,” he adds immediately, citing a high suicide risk among people with chronic pain. “Many of them get hooked on opiates.”

Yet it’s impossible to separate service from entertainment, especially when Waterson is on the table. I thought her tectonic neck crack would be the climax of the episode, but now, as Hightower places her on the office’s other table and as DeLeon Hightower moves in close, I realize that Waterson—and we, as viewers—are in for it again. I cannot imagine what joints on Waterson’s person are left to crack; I feel certain I have heard every one of her vertebrae align. But Hightower raises her legs until her back is flat against the table, then uses foam pins to situate her pelvis for an adapted Ring Dinger. (Hightower has done an adjustment on Johnson in a video, and vice versa.) He’s in the zone now, moving quickly and fluidly. He wraps a towel around her neck with a flourish and shoves a napkin in her mouth, instructing her to chomp down on it so she won’t bite her tongue. Waterson laughs through what is effectively a gag, but her eyes widen as Hightower positions himself behind her, putting his hands around the towel. I think of the rack, a device that would stretch victims’ limbs, something I learned about on a field trip to a torture museum. I remember thinking even then that it might feel good for a second (before the excruciating pain set in and I spilled the exact whereabouts of all my witch associates). Hightower pulls, and Waterson cries out through the napkin.

When she’s been ungagged and is able to speak again, she says, “I didn’t know I had all those [cracks].” Hightower tells her it’s a “two times a year” kind of move. After a few seconds, Waterson sits up, cheerfully shell-shocked. “I feel like I needed to sign a waiver for that.”

It’s not all theatrics. When DeLeon Hightower finally lowers the camera, looking satisfied, Waterson turns to Hightower. “Thanks,” she says, “I really needed that.”

Lauren Larson lives in Austin and is a features editor at Texas Monthly magazine.

Comments are closed.