I REALLY DON’T want to die here. That’s all I’m thinking as my toes maintain a death grip on the edge of the pool at a Life Time gym in midtown Manhattan. I’m surrounded by a swim instructor, a lifeguard, and a few people who are swimming around as if they actually like it. But I keep thinking of drowning. I have a crippling fear of the water, and

as a result, I have absolutely no idea how to swim. Yes, I’m 31 years old, and no, I cannot do a lap or even float.

That alone isn’t what troubles me, though. It’s that my lack of skill puts me in a petrified state that keeps me from living life to the fullest. If I’m forced to set foot on a beach (and let’s be real: I try to avoid it), I won’t even go into the water up to my ankles. If I’m on a boat, even if it’s the bougiest of yachts, you can find me wearing a life vest with my hand clenching a railing. I’ll only consider standing in a pool if it’s less than four feet deep. I never, ever take baths.

I’m not quite sure what caused my extreme aquaphobia. I have no recollection of being held underwater during a prank, having to dodge the jaws of a great white, or getting warnings from protective parents that left a permanent scorch mark on my brain. There is, at least, a little comfort in knowing that everyone’s scared of something. Whether it’s a fear of spiders or a fear of setting off a social-media disaster, each phobia has the same disruptive effects on our brains and lives. The fear response doesn’t discriminate; it works in the same way no matter what scares you shitless. What I do know is that I was sick of living this way. So I did something rash.

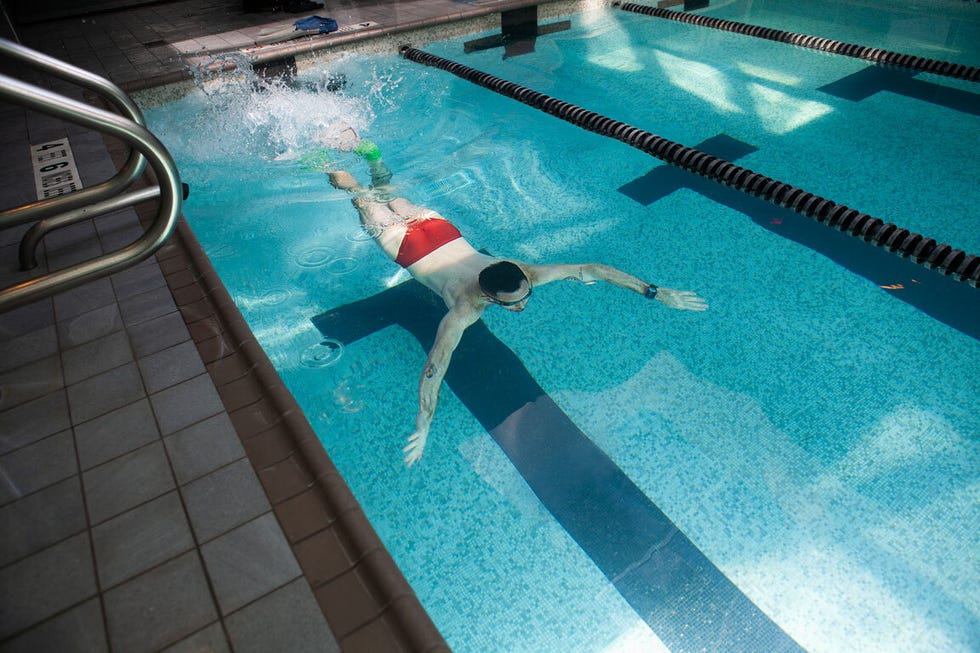

I signed up for eight weeks of one-on-one swim lessons with Life Time swim coach Kevin Dominguez. Trial by water. Whatever you want to call it, I was going to conquer my fear by plunging into its depths and learning how my fear—and all our fears—work.

My first lesson got off to a rocky start. I was supposed to learn to float, but I couldn’t relax even with the instructor holding me up. My heart rate climbed. I started overthinking, then panicking, and afterward I felt hopeless.

So I called licensed clinical psychologist Zach Sikora, Psy.D., who practices with the Northwestern Medicine Regional Medical Group in Illinois, to help me understand why I’ve been so scared of swimming and why it’s held me back for so long. Sikora says that my intense fear of dipping even a toe in the water is really just my brain doing its job. My amygdala, the brain region that registers fear, “is responsible for detecting threat in order to keep you safe,” he says. It’s doing exactly what it’s supposed to—it wants to keep me alive, so it’s sending warnings about water, which is the right response, since, after all, I don’t know how to swim.

Meanwhile, my frontal lobe—the part that takes care of reasoning—is trying to rationalize these thoughts and reduce the fear. That creates tension as one area is putting me on high alert and the other is trying to prevent me from succumbing to said fear.

Knowing that the fear and the stress around it are just biology, not a character flaw, helped me feel less apprehensive about the next lesson. But then I got in the water, tried to tilt my head to the side to breathe, and realized that my fear of dying via water had gone on the back burner. Now I was fully engaged in the fear of being a washout—I didn’t want to

waste my time, let alone my instructor’s. And I had a sudden fear of dependency when I determined I could only move around in the pool while holding foam noodles. The whole swimming endeavor felt like less of a physical challenge and more of an attempt to correct a personality defect. “It is common for anxiety to breed more anxiety. Your fear may be

specific to one situation, but then you find it in other areas,” Sikora tells me, calling it a “generalization of fear.”

That’s when I understood I might need even more support and wondered if I should call on my trusty therapist to help me become a fearless swim warrior. Instead, I called UCLA fear researcher Michael Fanselow, Ph.D., who explains that “it would be very difficult, if not impossible,” to just think my way out of this. To navigate this situation really well, I’d probably require a blend of exposure therapy via the swim lessons I was already doing and cognitive behavioral therapy, in which I’d practice reframing problematic thoughts.

This would help me establish pathways in the brain created by the thought that the water isn’t so bad. The process I was undergoing isn’t about getting rid of the fear response—that’s still important. It’s about helping my brain learn to select which association—the water is bad, the water isn’t bad—to act on when.

In the pool, I worked on gaining confidence and ability—“generating some evidence that you’re not going to drown,” as Julie Johnston, Ph.D., an expert in swimming and sport psychology at Nottingham Trent University, puts it. Both in and out, I worked on questioning established thinking patterns (“There’s no way I can swim”) and figuring out how to think in a more productive way about the water I was in (“breathe, kick, relax”).

In the third session, for instance, I managed to swim a lap using the tips of Kevin’s fingers as a guide. I wasn’t sure if his compliments were only intended to give me confidence or if I was actually doing as well as others do by this point. But I reframed that and realized that getting past this fear meant taking each victory as it came.

Initially, I struggled to separate the concepts of having a less-than-exceptional swim lesson and failing as a person. Eventually, I found an alternative and accepted that I wasn’t going

to be the next Michael Phelps and that I might never do a flip turn. I gave up that requirement to be successful and let go, dictating what the outcome of these lessons would be on my own terms. If I left each lesson with a pulse, I was happy.

The weeks flew by—some easier than others. I doubt a triathlon or an open water swim is in my near future. But I know that even if I never learn to love swimming, I don’t have to keep fearing the water. Nor do I have to keep worrying about letting my instructor—or myself—down. By understanding how fear works, I made every one of those 19-yard laps count (even the few that I walked). I came away from every session with a pulse and a little more wisdom.

I’ll take that as a win.

Your 3-Step Plan for Managing Fear

Normalize It

Recognize that fear is just your brain doing its job of protecting you. It’s good to be afraid of things that can hurt you. Knowing this keeps you from fighting what you’re feeling and getting even more tense, agitated, and incapable of dealing with the problem.

Flex Your Expectations

It’s important not to set a timeline for getting through your fear. When I accepted that I wasn’t going to be crush ing 3,000 yards after eight weeks and chose a realistic goal for each session, I gained control over the process.

Call in Backup

Exposure therapy—getting in the pool—was vital for getting through my fear. But so was learning to identify and challenge the dysfunctional thinking (“the water is going to kill me”) that was perpetuating my anxiety.

This story appears in the July/August 2023 issue of Men’s Health.

Sean Abrams is the Senior Editor, Growth and Engagement at Men’s Health. He’s a former hip hop dancer who likes long walks on the beach and large glasses of tequila. You can find his previous work at Maxim, Elite Daily, and AskMen.

Comments are closed.