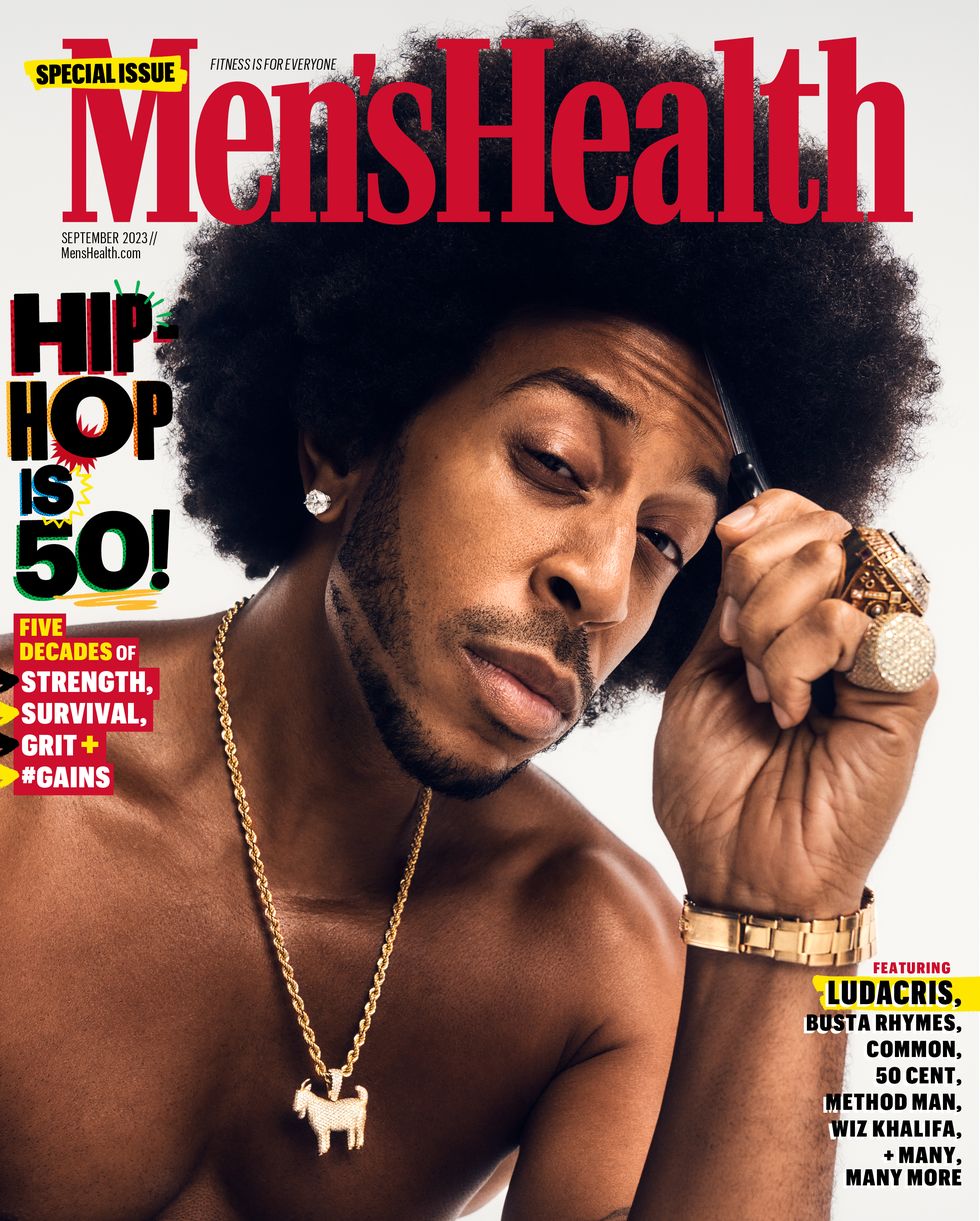

This cover story is part of Hip-Hop Is Life, a series of profiles and features that revisit key moments in the intersection of hip-hop and Black men’s health over the last 50 years. Read the rest of the stories here.

IT’S NEARLY DUSK and Chris Bridges is putting 12,000 or so fans to the test in a game of finish the lyric. He zips through a cadre of hits—“How Low,” “My Chick Bad,” “Money Maker”—delivering a few bars before signaling to the crowd to finish the rest of the verse.

The rapper and actor, better known as Ludacris, emerged at the dawn of the millennium. His irresistible, multiplatinum earworms dominated the rap charts in the early ’00s and cemented him as a Dirty South rap icon—his knack for polysyllabic rhymes and ribald humor offering a lighter counter to the gritty trap largely defining southern rap at the time.

“To have songs that after two decades I’m able to perform and they’re still ingrained in hip-hop culture, that, to me, is a testament of aging like fine wine—or standing the test of time,” Bridges says. “It’s like, humbly speaking, man, it’s so amazing, because it’s hard for an artist to be like, I got a hit song. After 20 years, you have to let the culture and the fans decide how much of a hit song you feel you have.” A smile flashes across his face. It’s a few days after the 45-year-old father of four played to a sold-out crowd at the historic Hollywood Bowl, and he’s still basking in the glory of the crowd matching him bar for bar for an hour.

Hip-hop has always been a young man’s game. It’s a genre where commercial relevance is largely dependent upon output—and one that, more tragically, loses its stars at a high rate. A 2015 study by the independent news outlet the Conversation found male rappers to have a life expectancy of just 30 years, with violence being the leading cause of death. Since 2018, we have lost XXXTentacion, Nipsey Hussle, Pop Smoke, King Von, PnB Rock, Young Dolph, and Takeoff. None of these men lived to see 35, and Bridges lets out a heavy sigh at the mention.

“[We’ve seen] a lot of our heroes starting to pass away, and even younger ones. There’s drugs; there’s health issues. Because of social media, we’re reminded of that every single day, and I think people are taking a little more responsibility for their health and being proactive,” he says. “I want to live for as long as I possibly can. Not only for myself, but for my children and my future children’s children—and to perform at the highest level that I possibly can for those fans that know my songs, word for word, for decades to come.”

When Bridges was 29, he lost his father after a long battle with alcoholism. His father dying at 52 was a catalyst for Bridges to prioritize his own health. “By the way, he was the most loving person on earth, the best person in this world. But people can look at the issues they’re dealing with and they can choose to learn from people’s mistakes and learn from people’s successes. So one of my major things, moving forward, is making sure I’m constantly healthy, because I knew that he had a disease, and it was eating away with him and eating away at him. And that’s the reason why he passed away at an early age. The most important man in my life showed me that you have to take care of yourself in a very roundabout way.” Almost daily he practices 52 Blocks (a New York City street-fighting style) and martial arts with two trainers, which helps him maintain his mental health.

“I don’t need a psychiatrist or a psychologist because I work with two different trainers. I’m literally telling them all of my fucking problems and they’re telling me theirs while we’re working out, so it’s almost like two different things that help you with your health: Working out and then speaking about all the shit that’s going on in your life is happening simultaneously. That’s probably why I’m one of the most emotionally stable artists on this earth,” he says with a laugh.

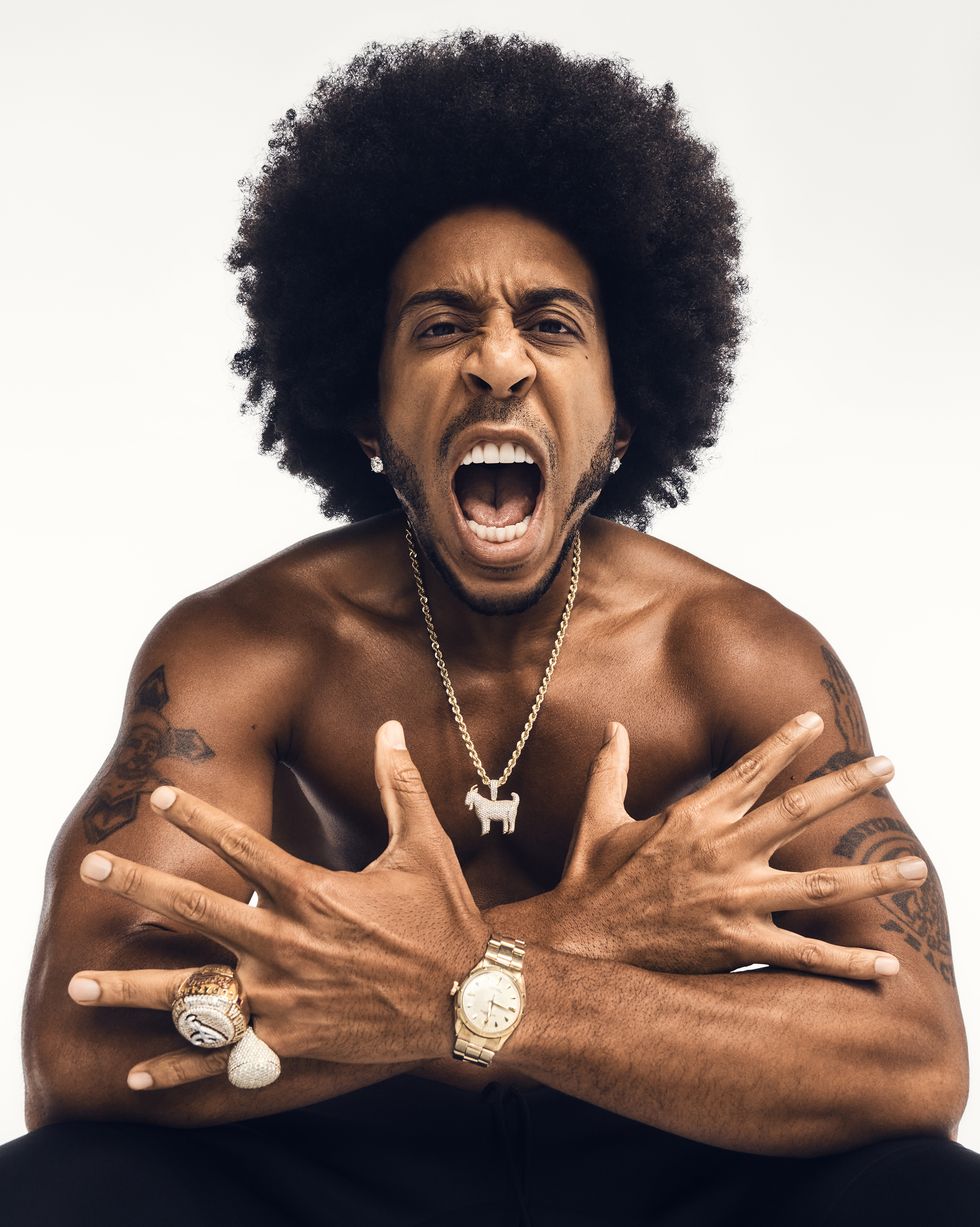

The Ludacris of today doesn’t look much different from the 23-year-old who broke out with “What’s Your Fantasy,” a bouncy (and deliciously raunchy) record about carnal pleasures… you know the chorus, “I wanna li-li-li-lick you from your head to your toes.” Arms chiseled, Afro perfectly coiffed, his signature muttonchops sculpted in an intricate pattern. The thought of rapping to crowds 25 years later never crossed his mind.

“Someone would get in their 40s or 50s and that was a stigma—like, ‘Okay, you’re too old to be doing music now,’” he says. “But nobody’s taking into account that hip-hop is only 50 years old. We’re still in the midst of seeing how [hip-hop] is growing to a degree, and so there’s no more ‘You’re too old.’” He adds, “Listen, I love to age, because I feel like aging is a privilege. The reason I’m so happy where I’m at is because I don’t have any resentments or any regrets. I have lived my life to the fullest. So when anyone remotely calls me OG, or anyone wants to throw around the word ‘old’ in the future, I’m not going to get upset—every human being has to go through these stages.”

But he’s self-aware enough to know that “there is a point in which you kind of want to let the new generation take control. It’s called hip-hop for a reason. I remember Andre 3000 saying, ‘You have to be in the know, you have to be hip.’ If you don’t change with the times, you will become your own worst enemy. I’m a person who embraces everything new because I love the newness and the evolution of hip-hop. Yeah, but I can’t say that for everybody in hip-hop. Then sometimes they become the older grumpy person.”

Bridges sees himself onstage for as long as possible, like a hip-hop version of legendary rocker and septuagenarian Bruce Springsteen. “I think people are going to be able to do it well into their 60s and 70s; if their content is speaking towards what’s going on in their life and the music is good, there will always be an audience for it.” He’s having too much fun doing it to stop anytime soon, though he sees himself releasing new music only for the next five to ten years, in favor of moving behind the scenes. For now, he’s relishing the fact that there are still audiences that want to see him lay it all out on the stage.

“I literally leave everything on that motherfucker. When I come off of there, I’m sweating, I can’t breathe, my voice is almost gone. If you pay to come see me, I’m giving you everything I got,” he says. “I am noticing [my] age, but I’m up for the challenge. I’m a warrior.”

A version of this story appeared in the September 2023 issue of Men’s Health.

All shoots and interviews for this cover were conducted prior the SAG-AFTRA strike.

Gerrick Kennedy is an award-winning journalist, cultural critic, and author living and working in Los Angeles. His new book, Exhale, an exploration of the life and career of Whitney Houston, will be published in 2022.

Comments are closed.