Before Stephen Anthony Smith became Stephen A.—the loud, emphatic, brutally honest host of ESPN’s First Take—he was a scrawny Black kid from Hollis, Queens, with dreams of a pro-basketball career. Those dreams were quickly derailed when he busted his kneecap during his first year on the Division II team at Winston-Salem State, but it paved the way for a new dream: to land a job at the worldwide leader in sports and become one of the most prominent figures in sports media; to become a guy who’s listened to, not just heard.

At 55, Smith’s done just that and more. Love him or hate him, the one thing that’s not up for debate is his work ethic. He climbed his way up the ladder reporting at the Philadelphia Inquirer, made it to ESPN and ventured into sports talk radio, secured his own TV show, got fired from the network, returned, landed First Take, started a production company, launched a podcast. He’s hustled. Hustled some more. And he’ll probably continue to hustle until the day he dies. However, the one thing he hasn’t done, up until today, is become an author. And to become an author, Smith says, he needed to write about his own story first and how, against the odds, he got here.

But not until his mother died.

More From Men’s Health

On June 1, 2017, the greatest woman he’s ever known passed away from colon cancer. A few years earlier, he promised his mother, a notoriously private person, that he would wait to tell the story of his life—from his impoverished childhood to his complicated relationship with his father—until she was gone. Before doing this, though, he had to confront the sadness that engulfed him. The Stephen A. First Take viewers were used to seeing yelling about the Cowboys or going off on his then-co host Max Kellerman about Tom Brady was a shell of himself.

“I was on the air every weekday, and there were times I hadn’t heard what folks were saying,” Smith tells Men’s Health. “I was incredibly moody. I didn’t care how I felt. I didn’t care whether I lived or died. The only thing I cared about were my two daughters. Nothing else mattered.”

For the first time in his life, Smith started therapy that October, which would eventually help him begin the four-month book writing process in 2021. It was emotionally challenging digging up long-buried memories—memories like his undiagnosed learning disability, his brother Basil’s death, his on-air controversies—but the book is far from all doom and gloom. On the contrary, it’s quite inspiring. Throughout the memoir, he also discusses the blessings of fatherhood, the lessons of navigating corporate bureaucracy, the people who lifted him up along the way. Ultimately, he wants people to understand that he’s more than a “personality”—he’s human—and, despite all he’s been through and achieved, he’s far from finished.

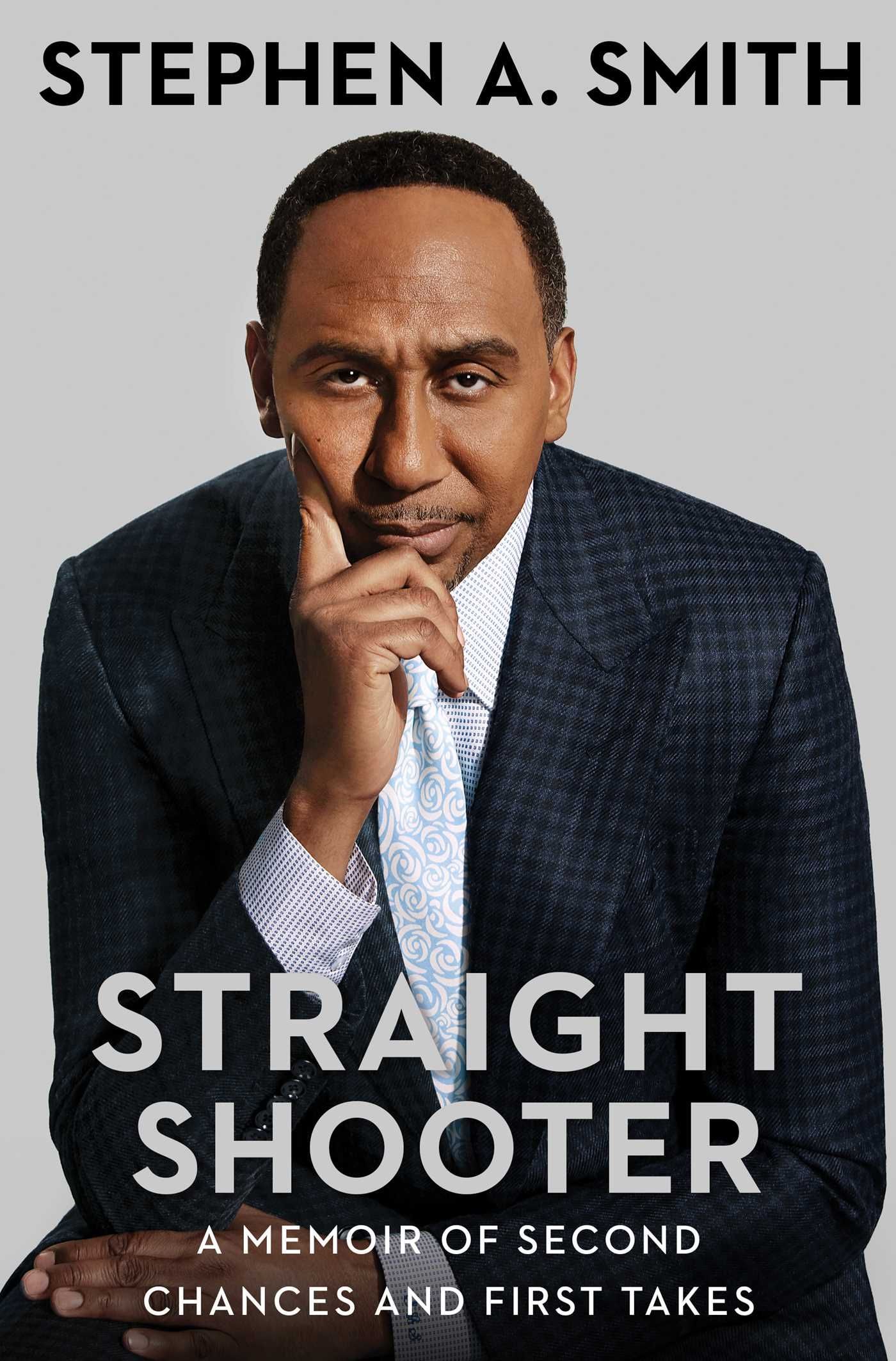

Ahead of the release of Straight Shooter (out today), the self-proclaimed “equal-opportunity flatterer and offender” chatted with Men’s Health about everything from his new outlook on life following a life-threatening battle with Covid to his future with ESPN to the lessons all guys can learn from this game called life.

Men’s Health: Before First Take, there was Quite Frankly—your sports talk show that debuted in 2005, a.k.a. the pre-Twitter days. Had you known the role social media would play in regards to how you receive and respond to criticism, do you think you still would have pursued a debate-style talk show?

Stephen A. Smith: Yeah because I’m not running from anybody. Social media doesn’t scare me. Most of the time, I just post my work and the things that I do that are work-related. I don’t really get into my personal stuff on social media. And I don’t read everything everybody says about me because then I’m living with the criticism as opposed to my words and what I say, feel, and think.

The thing that people miss is that I’m a journalist by trade. I was a beat writer. I covered high school sports, then colleges, then pros, then became an NBA columnist before I was a general sports columnist. I’m a veteran in the world of journalism. My mentality is that you run from nothing. We’re the fourth estate. We hold people accountable. It’s what we do. You can’t do that if you’re running from accountability yourself. I’m accustomed to being in the lion’s den. I accept the fact that the lion’s den comes with [criticism], and I embrace it.

It’s a challenge for me to be in my P’s and Q’s at all times. I’m not flawless. I’m going to make mistakes. All of those things are true. But at the end of the day, I’ll put my record up against anybody to be on live television every day, no tape delay. I’ve done well over 35,000 takes over the last decade live. I’m not going to be perfect. Of course I’m going to find myself in a hot seat from time to time—[I] may have said something the wrong way, may have said the wrong thing, or whatever the case may be. But I’m made for it. I live for it. It doesn’t phase me in the slightest.

When discussing your appreciation for sports after your brief stint covering crime you write, “There’s euphoria and misery in sports—but not death. There’s blood, sweat, and tears—but not death. There are winners and losers—but not death.” This made me think of the Damar Hamlin incident. Unlike your buddy Skip Bayless, who was widely criticized for his initial response, your empathy remained intact. Do you credit that to your reporting days?

I credit that to my humanity. As much as I love sports, there are times that the games don’t matter. Real life always takes precedence. And especially in the divisive days and times that we’re living in, it’s more important than ever before to put our humanity on display, to remind the world of what our better selves consist of. Whoever it is, you may look at me on TV. You may see me. You may not like things about me. Hell, you might not like me. But what you’re not going to do is meet me face-to-face and ever consider me someone who is inhumane, who doesn’t care about people, or who wishes ill will upon another human being. I’m not built that way. I wasn’t raised that way. I was raised to call it like I see it. And, sometimes, it may come across a bit harsh. But I’m talking about wishing for something, or being completely oblivious to the human side of things. No, that’s not me. I’m not made of that cloth. I’ve never been that person because of the kind of man [my mother] raised me to be.

After you were fired from ESPN in 2009, you ran into Pat Riley and said your goodbyes, but he refused to shake your hand and told you that you’d be back. You said that his words “saved my career and, possibly, my life.” Does Riley know how much that moment meant to you?

No, he doesn’t. I’ve never really said anything to him. And the beauty of Pat Riley is that I don’t think I had to because when you’re a winner the way that he is and you’re as brilliant as he is, you recognize what kind of impact he could potentially have. And it’s deliberate and intentional. He touched the strings to challenge me to lift myself up. It’s one of the more emotional moments I’ve ever had in my career because he was Pat Riley, and he didn’t have to do that.

I wasn’t going to kill myself or anything like that, but when I talk about it saving my life, I’m talking about the life that I could have had thereafter. [I] could have went into an abyss. Could have given up. Could have accepted that this is it for me. Then went onto something different that never would have been as rewarding, as fulfilling, as enjoyable. But he reminded me it wasn’t over. And it’s only over if I accept that it’s over.

When I made it back into the industry, I don’t recall where it was, we were walking by each other in the hallway and he just winked at me and kept walking. Then years later we were in Vegas. I was at the Wynn Hotel, and I was sitting by the bar. He was walking through because he happened to be in the same hotel that night. And he just came up to me and gave me a big hug. And then he said, “Let’s have a toast to you.” I had my bodyguard with me, and he wanted to know why. Pat Riley never said it and I never said it, but I knew exactly why.

You talk a lot about the responsibility you have as a Black man to represent your community. How have you managed to balance that responsibility while still being unapologetically yourself?

Number one by being fair. By trying to gather as much information and educate myself on issues as much as I possibly can. But more importantly, I never feel an obligation to agree with my community. I believe we all have a right to think the way we want to think. But I do feel a responsibility to make sure that the perspective emanating from my community is heard, even if I disagree. For too long, as African-Americans in this country, we felt voiceless. And that is something that I do feel an obligation to eradicate—that feeling of voicelessness. I want the Black community to always know that they have somebody in me that’s going to at least tell the world what we’re feeling and why, whether I agree with it or not.

In December 2021, you had a near-death experience with Covid that changed your outlook on life. Tell me about this experience and the new outlook that you have?

I woke up one day, in mid-December of 2021, and I had a 102.7-degree fever. I was sweating bullets while shivering at the same time. A few days later, I was labored with my breathing. The cough was persistent. Delusions had kicked in where I literally woke up at night and had to go to the shower to wipe the Covid sweat off of my body because the clothes that I was sleeping in, it was the equivalent of me being fully clothed and jumping into a pool or ocean. That’s how wet I was. [I was also] lightheaded.

So, when you go through something like that, it’s bad enough. But then when you go to the hospital on New Year’s Eve and the doctor tells you, “You’ve got pneumonia in both lungs, you should not be this bad, this is incredibly serious, and we’ll know in the next three to three-and-a-half hours whether these steroids and antibiotics that we’re about to give you is going to work” it blows you away because a part of me was ready to give up. I was like, excuse my language, fuck it.

And the reason why I was that way, and I had that kind of attitude, was because I had gotten so disgusted and tired of Covid. “Oh, if you touch this car door, you could get it. If you get into an Uber and touch this handle, you can get it. If you sit in a seat, you can get it. If you go on a plane, you can get it. If you go to the store, you can get it.” It got to the point where literally walking outside and the air could hit you because it might have been airborne, like from the movie Outbreak, you’re done. And my attitude was, to hell with all of this. Whatever’s going to happen is going to happen.

To get to that point, where I felt that way, was tough. But ultimately, three-and-a-half hours later, when the stuff clearly had kicked in and I took a turn for the better, it gave me an opportunity to reflect and think about all of the things that my daughters, my family, and everybody who tried to get me to think about what I wouldn’t think about. The challenge for me is I know that I want to, and that I need to, spend more time with my daughters, work a little bit less, etcetera, etcetera.

But what a lot of people don’t recognize is the mandate that was handed down to me by my mother. “I’m gone now. You’re the patriarch of this family. And I need you to make sure you watch everybody’s back. You don’t have to sit up there and take care of everybody. I’m not asking you to do that, Stephen.” That’s what she said to me. She said, “You have the means and the intestinal fortitude to take care of other people, and I need you to do that.” And so, I’ve got 15 nieces and nephews. I have my two daughters, and I have my four older sisters. I’m the first one to graduate from college and obviously I’m making the most money.

When all of those things are things that have draped you, and you hear this mandate from your mom, you soon deduce that the best way for you to do that is to be as successful as you possibly can so you can be there for people when they need you to be there. That’s a position that I dance back and forth with. At the end of the day, it does come down to me being the best man that I can possibly be and the best father that I can possibly be, the best brother, the best uncle. I love working. I don’t like the bureaucracy that comes with it, but I love the work that I do. There is a side of me, [however], that recognizes that there’s more to life than just this, and I need to remember that.

There are so many people that helped you get to where you are today. What’s your advice for guys out there struggling to find those people in their own lives?

Everybody in life has someone who cheers them on, has someone who supports them, has someone who can play the role of an advisor, a mentor, a cheerleader, etcetera. Value them. Don’t just use them. When we use people, we’re not thinking about them—we’re thinking about ourselves. We get what we can from them, and then we throw them away, never realizing that if you cherish them and you value them, they’d never go away. Because they’ll know they’re appreciated and that you thought about someone other than just yourself. That’s the difference.

You have two-and-a-half more years left of your contract with ESPN. Is there a world waiting for Stephen A. that doesn’t include ESPN?

Possibly. I don’t have an aspiration to leave ESPN. I don’t have an aspiration to leave sports. I do, however, have an aspiration not to be limited to it. And if the choice is to be limited to sports or to leave sports, then I am prepared to leave. As much as I love the bouncing of a basketball, the catching of a touchdown, the home run of a baseball, the boxing matches, and all of these things, the difference is that once upon a time there was a dependency coupled with the desire. The dependency is gone. I don’t depend on it anymore to fulfill me mentally and emotionally. I have other fish to fry.

Do I want to do late night television? Yes. Do I want to produce scripted and unscripted content for television and film? Yes. Do I want to be a successful podcaster if I’m fortunate to pull that off because this is my first foray into podcasting? Absolutely, yes. These are things that are incredibly important to me. People who want to facilitate me achieving those goals are who I want to work with and for. People who don’t want to facilitate me achieving those goals are not people that I want to work with or for.

You mentioned that you’re relatively introverted off the air. What’s the biggest misconception about yourself that you hope people will learn while reading this book?

I think people don’t know how deep my humanity goes, my love for people that I truly, truly, truly never wish any harm upon anyone. Just because I’m calling something like I see it doesn’t mean I wish it was that way. I want us all to eat. I want us all to be successful. I want everybody to be happy—just not at the price of me. I don’t think people understand that, and I don’t think that people realize how family-oriented I am. I don’t like parties. I don’t like crowds. I deal with them, but I don’t like them. My definition of having a good time is having family, friends, and loved ones around in a party-type atmosphere, like a Fourth of July barbecue or a birthday party. Anything that has me around an abundance of people that I love is when I’m at my most comfortable self.

Do you have a dream reader? A specific person or group of people you hope this memoir gets in the hands of?

That’s an interesting question. I haven’t thought about it. I would tell you I hope Oprah reads it. I hope Barack and Michelle Obama read it. I hope my friends, my contemporaries in this business that I’m friends with, the people that I grew up with, I hope they read it because remember, I haven’t told these people all of these things. There are things that they would learn about me that would shape the foundation of who they thought I was, who I am, and who I’ll always be.

But the book is for everybody because the ultimate goal is for it to serve as a motivational tool to inspire folks to move forward and march on no matter what adverse circumstances they’re confronted by. And those who have the ability to reach the masses, to touch the lives of many other people, I sincerely hope those people read this book as well because I want them to have that kind of impact. I want them to utilize my book as a tool to help impact others in a very positive way.

Even Cowboys fans?

No. Not them. I don’t think Cowboys fans can look beyond their Cowboy fandom to see anything else. I think Cowboy fans will read the portion of the chapter where I talk about why they’re disgusting and nauseating in my eyes, and I think that’s all they’ll see. That’s who they are. I love hating on them, but it’s all in fun. It’s nothing serious.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Deputy Editor

Rachel Epstein is the Deputy Editor at Men’s Health, where she oversees, edits, and assigns content across MensHealth.com. She previously held roles at Marie Claire and Coveteur. Offline, she’s likely watching a Heat game or finding a new coffee shop.

Comments are closed.