This story is part of our annual Fit At Any Age series—a guide to the innovations and breakthroughs in aging to help you live a stronger, longer life.

ASK THE MAN who is arguably the world’s top researcher on friendship exactly how many friends he has and the answer might surprise you.

“I don’t have any friends,” deadpans Robin Dunbar, Ph.D. “I’m a bloke.”

Clearly, that’s a joke. But you’ve probably felt that way, too, at times. Survey after survey shows that more than half of men are feeling lonely, and many of us say we have fewer close friendships than in years past.

What happened? Maybe you started a new career or relationship or had kids. Maybe you moved to a new city or even the neighborhood a couple miles over. As men get older, we seem to get lazier about devoting time and effort to maintaining friendships or trying to make new ones. Being social-media “friends” isn’t the same, and the shift to remote or hybrid work probably isn’t helping, which may explain why loneliness has become an epidemic among younger generations.

You might not think you have the time to change. But forging stronger friendships is one of the easiest ways to boost your health and happiness. Dunbar, an evolutionary psychologist at Oxford and the author of Friends: Understanding the Power of Our Most Important Relationships, says friendships improve our lives because they generate endorphins, pumping out “what philosophers I know always refer to as raw feels.” Great friends can also provide (cringe alert) “a shoulder to cry on”—so you bounce back quicker during hard times.

People with strong friendships are less likely to catch a cold than those who are socially isolated. They have a lower risk of dying from heart disease or cancer and are less likely to become depressed. “There’s been a complete tsunami of publications showing that your mental and physical health and well-being, and even how long you live into the future from now, is best predicted by the number and quality of close friendships you have,” Dunbar says.

The men in the following stories all share a similar lesson: No matter what age you are, true friendship can make you more excited about what’s next. —Ben Paynter

Jump to each section:

THE ACTION ON the softball diamond in St. Petersburg, Florida, goes like this: Pitcher Jerry Wollman jaws at hitter Peter Calabrese, who leans his barrel chest over the plate. Wollman lobs the ball, Calabrese swings hard, and a two-hopper skips toward the shortstop, Gordon Norton.

Norton hustles, cleanly gloving the ball and pivoting to throw to first, while Calabrese charges down the line. The toss is strong but fading low, so first baseman John Draeger stretches for the out.

Most of the ballplayers here have spent years (in some cases decades) finding that rhythm together. Wollman is 85. Calabrese is 83. Norton’s 85, too, and playing in his tenth season. Draeger’s the rookie, a comparative youngster at 75—only one year past the minimum age required to join the St. Pete Kids & Kubs, aka the Three-Quarter Century Softball Club, a four-team league that’s been around since 1930.

Local over-50 players set their sights on making the cut the same way high schoolers look longingly at the major leagues. Except there’s a fuller range of life experience here—from former doctors to accountants and factory workers—and no one cares if you’re a year-rounder or a winter snowbird.

Draeger, a psychiatrist who moved to the Gulf Coast from Hawaii, explains the psychic draw of the league in not-so-clinical terms: “We’re out there seriously trying to play well, maintain some level of exercise and fitness, and meet new people. It’s a very social experience.”

The longer they play, the younger they feel. —Gare Joyce

CHEF KELSTON MOORE knew he needed help. It was June 2020, and after nearly a decade in the Navy, the 31-year-old had gone to culinary school, become a personal chef, and relocated back to San Diego to be closer to his young son.

Disappointment after disappointment had made Moore feel that he had a lot to prove and needed to build himself into a respected chef alone. But his would-be signature dish—crab cakes—wasn’t holding together, which he took as a sign: Seeking advice, he contacted about 20 local chefs. Most of them ghosted him, but then Quinnton Austin, the 34-year-old owner of a restaurant called Louisiana Purchase, DMed him back on Facebook with a tip: Use breadcrumbs as a binder.

That helped Moore perfect his dish and marked the start of a larger collaboration built around selflessness, a value that Austin had already recognized in Moore.

Other chefs may have seen Moore as a threat or unworthy of their time, but for Austin, “there are better results when you bring people together,” he says. “Kelston came from nothing, just like me. His goals are the same as mine, where he wants to put people on [their way to success].”

The two cofounded Bad Boyz of Culinary, which runs events and programs to showcase the talents of Black and Brown chefs in the predominantly white San Diego culinary community. Austin originally began the movement with a hashtag, #BadBoyzOfCulinary, to raise awareness of Black chefs to businesses everywhere—catering, restaurants, and personal-chef employers.

After Austin invited Moore to cook in some live events, Moore proposed turning BBOC into a nonprofit to encourage mentorship and provide scholarships. “Once it got started, we had no choice but to be around each other, because we were planning events together,” says Austin, who remembers the two of them hanging out at bars until 3:00 in the morning, bonding over stories about old relationships, the kitchen life, and their ambitions. “That’s when I began to know and respect him as a man.”

Today, Moore is an established private chef and runs dining services for private yachts, while Austin is the executive chef at seven restaurants. BBOC has five core members from different parts of the food world, all committed to helping one another and the next generation of cooks in the region. They can seldom all get together, but last March, Austin and another BBOC member joined Moore for his 33rd-birthday dinner, where they swapped stories about their lives well into the night.

BBOC may keep them in contact, but they’ve chosen to stay in each other’s lives. —Keith Nelson

THE TABLE TENNIS crew meets on Sunday. Usually late, after the kids have gone to bed. Three Brooklynites are always down to play: Grady Southard, 42, lawyer, father of one; Paul O’Reilly, 41, photographer, father of two; and Vib Sachdev, 39, lawyer, father of two. They play almost every week, sometimes until 2:00 a.m. It’s been five years straight.

“Compulsion sounds like it has a negative connotation,” says Southard, before describing the compulsion. (They compare table tennis to a need.)

At first, it was a reason to leave the house, to stay active and avoid previous tennis injuries, to hang out with other guys. Now they have dinners. Trips together. Their kids’ birthday parties. Random calls and texts.

“I think with any relationship, there’s just a greater connectivity the more that you get to share experiences with a person,” says O’Reilly.

And when they do play, it’s Zen. Compulsive Zen, but still: the focus on the table, a particular spin, a position for a return. It’s a break from life.

While the competition remains fierce, it never strains the bond among the three. “There’s no pressure [on the friendship],” says Sachdev. “If I have to lose, I love to lose

to one of my pals.” —Joshua St. Clair

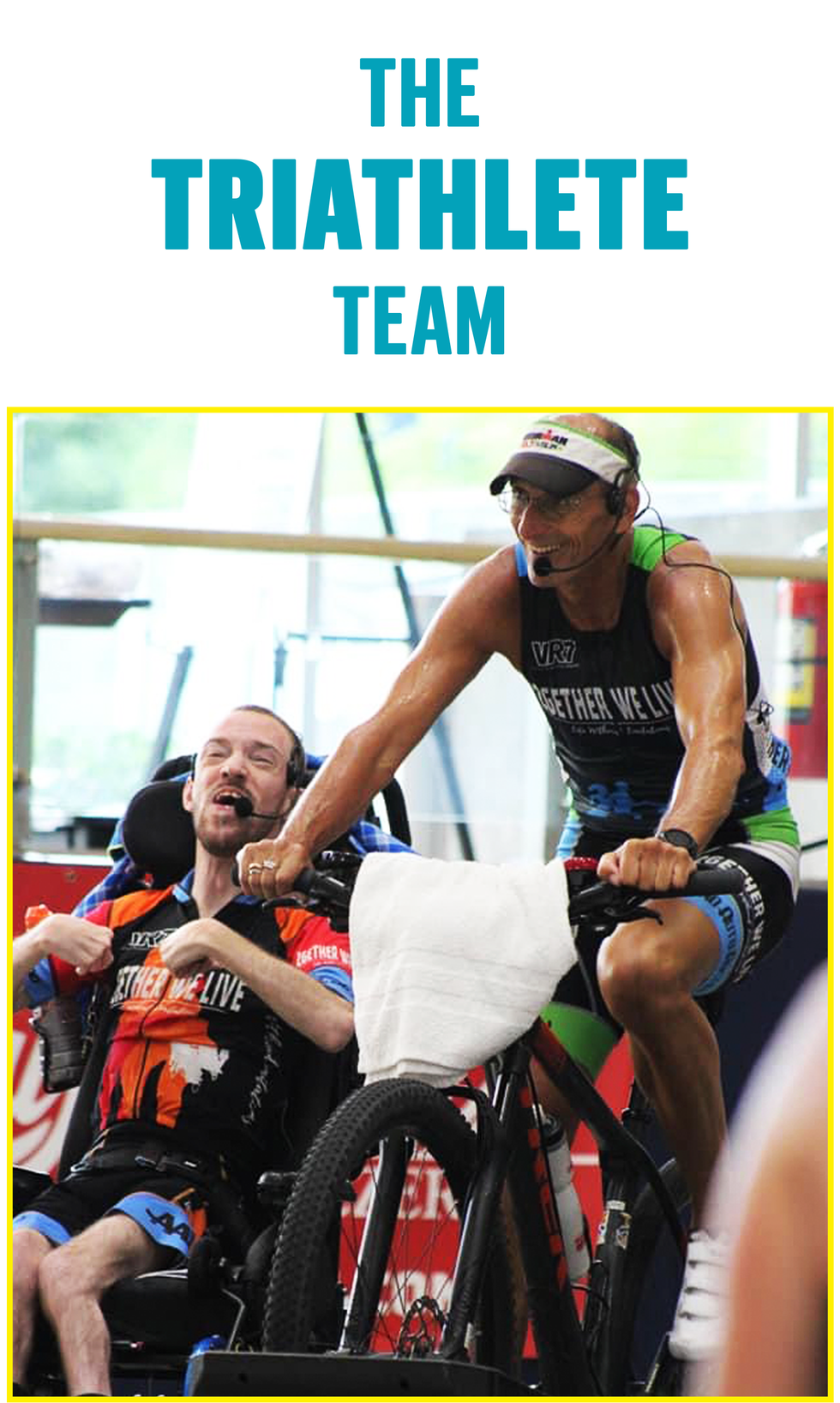

EVERY RACE DAY starts with a 3:00 a.m. wake-up call. Patrick Canez, 32, shouts, “Let’s go, I gotta race!” to the rest of his family. After all, he has a teammate to meet.

Canez, who has cerebral palsy that limits his speech and mobility, joined forces with Tim Bolen, 57, about a decade ago. “The friendship was instant,” says Sandra Canez, Patrick’s mom, on his behalf. “They were cracking jokes, and I could see the connection.”

Bolen, who runs the nonprofit 2Gether We Live, began training with Canez. They started racing 5Ks, then 10Ks, then marathons and triathlons. “He’s a guy that wants to be competitive,” Bolen says.

At the same time, they know they have only so many races left. Bolen was diagnosed with stage 4 non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in 2020; he’s expected to live about four more years. Still, they continue to set big goals, like finishing their first full Ironman. Each race has its own victory. “Before training, Patrick was not able to raise his arms,” Sandra says. “Now he can raise them—especially over the finish line.” —Paul Kita

THEY ONCE RACED side by side on the same New York cycling team. Decades later, Peter Sheehy, 55, lives in Los Angeles while Bernie Yee, 57, is in Seattle, but they’ve continued meeting annually for big rides for more than 30 years. “We have a shared history of doing hard things together,” says Yee.

Back in the ’90s, Sheehy was a beleaguered chef and Yee an unemployed attorney. Riding bikes became a lifeline for both. “Putting in miles together builds closeness,” says Sheehy. For his part, Yee considers the rhythm of each ride meditative and “a metaphor on how to find common ground.”

Sheehy’s now a history teacher who does triathlons, and Yee’s a video-game producer who races cyclocross. But they still appreciate each other’s perspective. “You bring to training and racing who you are in life,” Yee says. Sheehy taught him that. —Peter Flax

MARCUS RENTIE, 42, raced to keep up as his dog, Batman, took off after a coyote during their usual trail run. “My heart was beating out of my chest,” he says.

He lost sight of her. Then Rentie rounded a bend and spotted Batman happily waiting for him. “She’s like, ‘I chased him away. We’re good,’ ” he says, laughing.

Rentie has conquered 100Ks and 100-milers, but around the San Fernando Valley, he’s best known as “Batman’s dad,” he says. The duo train together and are both sponsored—him by Salomon, her by Ruffwear.

A former stunt Rollerblader, Rentie turned to running races in 2015 after a bad accident left him inactive with blood-pressure issues. Four years later, a friend asked him to foster an energetic husky-and-Australian-cattle-dog mix for just a weekend, so Rentie took her on a run. “I was supposed to do eight miles that day, and we ended up doing, like, 12 because she was loving it,” he says. “I was like, all right, this is my dog now.”

They’ve since found more ways to stay accountable and inspired. “Sometimes I’ll be like, I’m gonna walk this hill, and then I look up and she’s just handling it, so now I have to run it,” he says. “My goal is for her to be asleep on the car ride home. If I do that, then I know we’ve had a pretty good run.” —B.P.

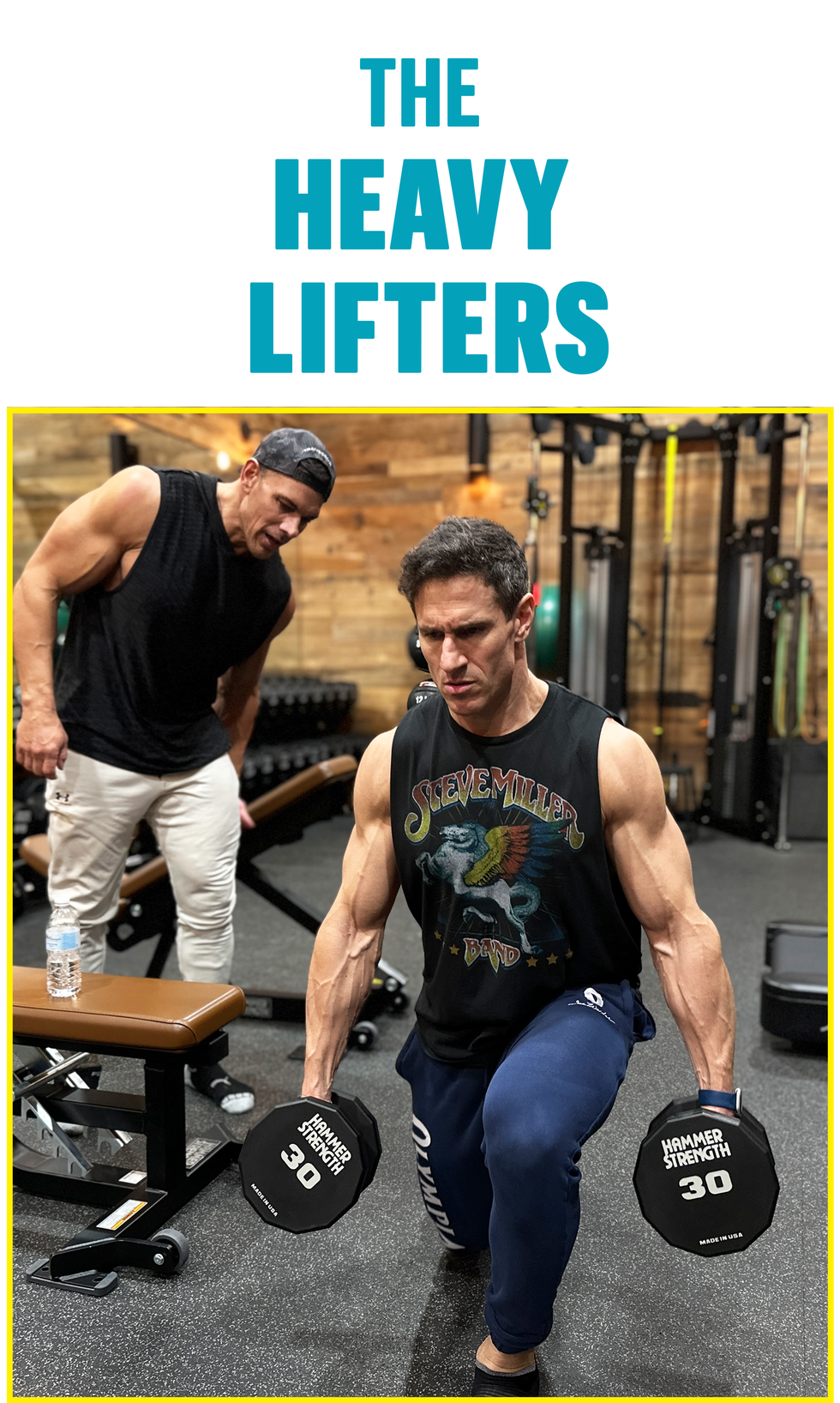

NO SHIRTSLEEVES ALLOWED. That funny rule sets the upbeat tone for the Sleeveless Workout Show that happens when trainer and MH advisor Don Saladino, NASM, 46, and bodybuilding icon Frank Sepe, 51, train together. Tune in to their weekly workout sessions on IG Live (@donsaladino and @frank_sepe) and you’ll see that they’re not just sweating and grinding. “We’ll be laughing our ass off between sets,” says Saladino.

The men have known each other for decades, but it took surviving a global pandemic for them to realize they might find more motivation by joining forces. They’ll try things like workout-ending “strip sets,” where one guy does eight to ten reps on a leg press, resting only momentarily as his friend strips off some weight. “Three or four sets like that will fry you,” says Sepe. They leave with their spirits lifted, too. —Ebenezer Samuel, C.S.C.S.

This story appears in the April 2023 issue of Men’s Health.

Comments are closed.