AN ALARMING NUMBER of men— 45%, by one recent study’s count —are walking around with a sexually transmitted infection (STI).

And, one of those STIs could be putting both you and your partners at risk for several kinds cancer. The human papillomavirus (HPV) has been linked to anal, penile and oropharyngeal cancers. Doctors have recently experienced an uptick in oropharyngeal, or throat cancer, cases that are related to HPV. Nearly 70 percent of oropharyngeal cancer cases are linked to HPV, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

HPV is sexually transmitted, and so, the main risk factor for oropharyngeal cancer is number of oral sex partners. In fact, research has found that those who participate in oral sex are 8.5 times more likely to develop throat cancer than those who do not.

Most people who acquire HPV are able to clear it out of their system successfully. But, some people do not, likely due to a “defect in a particular aspect of their immune system,” says Hishem Mehanna, M.D., professor at the Institute of Cancer and Genomic Sciences at the University of Birmingham, in a story he wrote for The Conversation. “In those patients, the virus is able to replicate continuously, and over time integrates at random positions into the host’s DNA, some of which can cause the host cells to become cancerous.”

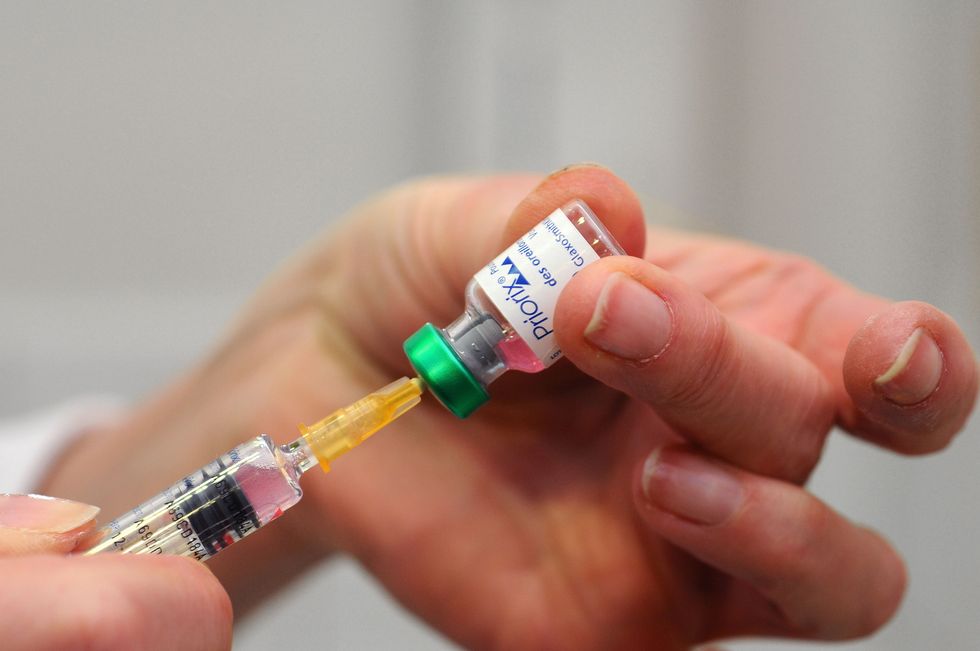

The good news is there’s a vaccine that significantly reduces that risk. The kicker? Not that many young men realize it’s available and that they should get it.

HPV is now the most common STI in the country, with approximately 43 million people in the United States infected. Because certain HPV strains increase the risk of various types of cancer, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends that boys and girls get vaccinated between the ages of 11 and 12.

But according to data that was presented at an Annual Meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Oncology, 65 percent of girls have completed the vaccination schedule for HPV, versus 56 percent of boys—even though the vaccine has been widely available for more than a decade.

What is HPV?

For context, HPV is a group of approximately 200 viruses that spread via vaginal, oral, and anal sex. (It can also be spread via “heavy petting,” per the CDC’s somewhat anachronistic language.)

Usually, people with HPV show no symptoms. But the low-risk strains can cause genital warts, while the high-risk strains can lead to cervical cancer, oral cancers, anal cancer, and rarer forms of genital cancers. In fact, the CDC estimates that, in men, about 89% of anal and rectal cancer cases can be attributed to two strains of HPV, along with 72% of oropharyngeal cancer cases.

Currently, an estimated 80 million people living in the United States — or about a quarter of the population — are infected with HPV, with about 14 million new infections among teens and adults alike each year. In fact, it is so common that the CDC warns that if you’re having sex but are not vaccinated, you’re probably going to get HPV at some point. (The CDC recommends men get vaccinated before they’re sexually active, preferably before the age of 26, but it is possible to get it if you’re older.)

In fact, you might already have HPV and not know it. For men, there’s no approved test (although some health care providers do offer anal pap tests, if you are a man who receives anal sex).

So why don’t all boys get the vaccine?

Well, a few reasons. For starters, the HPV vaccine simply hasn’t been around that long: the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the first HPV vaccine, Gardasil, in 2006. At that point, the CDC recommended it only for girls and young women, due to early data asserting a link between HPV and cervical cancer. So doctors focused on vaccinating young women, explains William Schaffner, MD, a professor of preventive medicine and infectious diseases at the Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

The data on boys and HPV didn’t come in until later, Schaffner says. So in 2011, the CDC expanded the patient pool to include boys and young men ages 11 to 26. Although health care providers were encouraged to recommend the vaccine to young men from that point on, HPV’s association with so-called “female” cancers still lingers to this day.

What’s more, Schaffner adds, the fact that HPV is an STI carries a lot of stigma, particularly among parents who are loath to the suggestion that their kids could be having sex. “Rather than the emphasis on cancer prevention, there was so much more discussion, initially, on how the virus was transmitted, which seems to me to be beside the point,” he told MensHealth.com.

“For the first time, we had an anti-cancer vaccine against a whole series of cancers. It was an extraordinary triumph. But that kind of got lost.”

What should parents and doctors do next?

Due to that stigma, many doctors don’t consider the HPV vaccine a routine procedure for young men — and that may be putting them at risk.

“People are people, and that includes health care providers,” Schaffner says. “Talking about cervical cancer is easy, but then you start talking about vaginal cancer and penile cancer and anal cancer, that starts to be more of a sticky wicket.” Think of it this way: if parents get persnickety at the suggestion that their child should be vaccinated against a sexually transmitted infection, it is not terribly hard to imagine how they might react to the suggestion that their son be vaccinated for a disease spread via anal sex specifically.

The solution to all this, Schaffner suggests, is easy: regardless of the mode of transmission, doctors should treat the HPV vaccine the same way they would a tetanus shot. Providers should be prepared to answer questions, but needn’t call any special attention to HPV. The shot should simply be part of a standard vaccination menu offered to all patients, regardless of gender.

“If we could address provider hesitancy,” Schaffner says, “we would win the day.”

Comments are closed.