While arguments over the validity of “video game art” have thankfully settled over the last decade, the fact remains that adaptations of video games to other media often leave both old and new audiences wanting. Since its announcement, however, HBO’s The Last of Us has promised something more. Last year, it was announced Cannes Film Festival Best Director winner Kantamir Balagov would direct the pilot; that did not come to pass, but the completed episode lists boasts an episode by Oscar winner Jasmila Žbanic and two by Ali Abbasi, another emerging favorite on the arthouse festival scene.

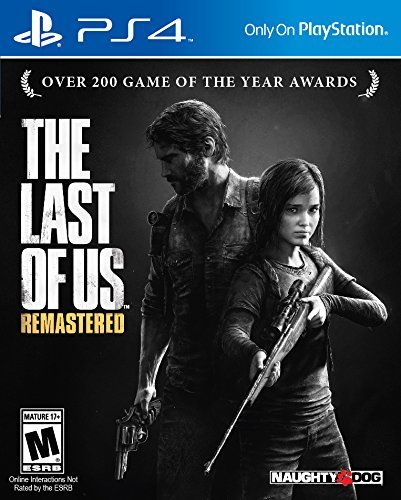

The game, whose acclaim rests primarily with its narrative, was written and directed by Neil Druckmann (who, along with Chernobyl‘s Craig Mazin, serves as showrunner for the adaptation) and follows a smuggler named Joel (Troy Baker in the game, Pedro Pascal in the show) as he ventures across the country with a teen girl (Ashley Johnson/Bella Ramsey) who might be the key to a cure to a fungal pandemic that has turned the world into an apocalyptic wasteland. It’s exactly the sort of premise (serious, with contemporary overtones) and thematic material (both formats take on grief, hope, and parenthood) that you would expect more from cable TV than a Sonic game. We can almost imagine an HBO-style tagline: “It’s not Detective Pikachu. It’s The Last of Us.”

While HBO’s The Last of Us is true to the game, those who have played it can look forward to differences, if not surprises. Don’t expect this 9-hour series to find Joel and Ellie wheeling carts around to hop fences or fighting off Clickers every time they need to get from one place to another—Joel kills exactly one baddie with his giant arms, and it’s not an infected one. Rather than constantly prolonging the next story beat with excitement, TV tends to focus on context and backstory, and there’s plenty of backstory to go around with The Last of Us. Where the game was locked into Joel’s point-of-view for all but a brief segment—meaning we see what he sees—the show takes a more omniscient one, showing us what other characters are up to and treating us to numerous flashbacks throughout its nine episodes.

There are also too many examples of condensing and abridging gameplay segments to list all such instances (the much calmer escape and a sacrifice in Episode 2 will give an idea of what to expect), but here are some of the larger changes viewers can expect to see—and we will keep this list updated as the show continues through its first season.

The Pandemic

The nature of the infection itself has been reworked to have overt contemporary analogues. The show opens in 1968, with two infectious disease experts discussing with a TV journalist the possibility of global pandemics. With clear echoes of the COVID-19 pandemic, the first of them warns of increased air travel enabling a mutated supervirus to spread easily, and if the contradiction of the other expert dismissing just viral illness to warn instead about fungi seems like cheap irony, it turns around. Of course, he notes, a cordyceps fungus that can take over the body of an insect can’t survive at the temperature of a human body, but if the earth were to “get a few degrees warmer,” its survival might dictate that it evolve to do so. In that event, he concludes, “we lose.”

Earth loses a bit faster on TV. The video game opens in 2013, the same year it was released, but takes place mostly in 2033. In the show, the pandemic breaks out in 2003, with most of the show taking place in 2023. Our present is no longer the onset of the pandemic but its endemic stage, and the totalitarian FEDRA is now openly discussed as fascist, with visual references to Operation Desert Storm and then-president George W. Bush positioning recent American governance as a natural precursor to a world of summary executions, saturation bombing, quarantine zones, and black market ration card trading.

Spores (Series)

This one has been making the rounds online ahead of the show’s debut: There are no spores in HBO’s The Last of Us. Masks would make for an easy parallel to our own pandemic, but this change is for the better. Nobody would believe the physics-defying spores that don’t expand beyond set borders on TV (isn’t it weird how opening a door or even a protruding hole in a wall or ceiling never led to expansion?) anyway, but, as noted above, The Last of Us is not concerned with our current pandemic, but with the next one. Nobody would have to do much thinking to draw a connection between characters masking up to prevent infection and our own reality, but don’t we want to have to do at least a little bit of thinking?

The Intro and the Boston Quarantine Zone (Episode 1)

The Last of Us boasts one of the best openings in video games, and the TV show expands it by detailing what happens in the day preceding that night-time opening. We spend ample time with Sarah, allowing Joel’s future interactions with Ellie to contrast more sharply, and we also get to know the neighbors who first introduce us to the game’s pandemic and see a bit of pre-pandemic life. The Last of Us Part 2 players will also get a chuckle out of a scene where Sarah and Joel sit down to watch Curtis and Viper 2, a movie absent from the first game but namechecked as Joel’s favorite in the second.

If that elaboration feels a bit unnecessary, the more involved look at life in the quarantine zone that follows it more than makes up for it. We see more of the work Joel and Tess do, with Joel establishing contact with a FEDRA soldier to swap goods. We see Tess’s tussle with Robert, the arms dealer who ripped off her and Joel, and his henchmen, which is merely alluded to at the start of the game. We also see how Ellie came into the protection of Marlene. All of this makes the TV show’s QZ a far more lived-in place than that of the game, which is virtually empty.

Lastly, Joel and Tess’s pursuit of Robert and subsequent meeting with Marlene and Ellie is altered a bit. He is dead before either party finds him this time, and the tense encounter and ensuing collaboration with Marlene in the game is replaced here with a tenser, guns-raised bit of dealmaking and, characteristic of this adaptation, with the action set pieces from the game excised.

We will continue to update this piece as Season 1 of HBO’s The Last of Us progresses.

Contributor

Forrest Cardamenis is a Queens-based film critic whose work has also appeared in MUBI Notebook, Filmmaker Magazine, Reverse Shot, and other publications. You can follow him on Twitter at @FCardamenis for his thoughts on movies, music, sports, and more.

Comments are closed.