WITH CONSISTENT PERFORMANCES and big plays, I was on the radar of NFL draft scouts. In football terms, I was closer than ever to being somebody, closer to a validation that less than a tenth of a percent of all high school football players get. On paper, I had a realistic path to achieving a dream—but I wasn’t sure whose dream it was. The questions in my head grew louder. Self-doubt about my sexuality and my identity overflowed into worries about the future. There was a bitter irony in how I was shrinking away from a dream even as my hard work had brought it within reach. The NFL wanted me, but only because they didn’t know the real me. My understanding of athletic success, in football especially, was that only a certain kind of man could play at the highest level. Athletes could only do certain things and be certain ways.

As I played my role at Purdue and blindly searched for meaning in private, I felt like I was living a double life before I even knew how each of those lives worked. I had hidden my creative side from my teammates throughout middle school and high school—and I was doing it again with my college teammates. I worried that a young man who wrote poetry, drew pictures, and enjoyed slow songs about love would be seen as less masculine and, therefore, less of a football player. Being actually queer seemed like an instant, irreversible verdict on my belonging, on my right to exist in the male world of football.

Between my junior and senior seasons at Purdue, Missouri’s All-American defensive lineman Michael Sam had publicly come out after the end of his college football career. He was drafted in 2o14, but he never made it into a regular-season game.

More From Men’s Health

When I first heard the news about Sam coming out, I remember I tried to differentiate us in my mind as much as possible. He was gay, not bisexual, so naming his identity publicly seemed more clear-cut, or maybe he saw it as his only choice. He was SEC Defensive Player of the Year, so he would have gotten a shot at the NFL regardless. I was in the Big Ten, and Purdue wasn’t one of the top schools in our conference: my future opportunities weren’t so obvious.

Also, he had someone. The video of Sam and his boyfriend kissing when he was drafted played every hour on the hour that draft day, exposing what a lot of my peers, teachers, and family really thought about two men kissing. But I did all these mental gymnastics because deep down, I knew that in the most significant ways, we were the same. We were both different from what we were told from birth that a football player should be. We were Black, which meant society already judged us more harshly. And we both wanted to play in the NFL more than anything. Our very being threatened our biggest dream. I was afraid for him. I was afraid for myself.

But at that moment, in 2o13, there were no out football players as far as I knew—not in college, and definitely not in the NFL. Purdue’s nonconference schedule was off to a good start; we beat teams that we were supposed to beat, and thoroughly. But duality was a tricky beast. There were moments when I donned the Purdue black and gold that I felt like I was fulfilling my purpose. Other times I felt like a complete fraud. I didn’t yet know that I would only feel right when I brought my two sides together. In fact, the possibility of those two sides coming together was my worst fear.

The potential consequences of my worlds crashing into each other—would both of those sides be obliterated?—was the strongest fear I had ever felt. All the success I found on the field I attributed to my dedication, my hard work, my masculinity, my sacrifices. All the failures I blamed on my duality. A bad game was never just a bad game but a knock on my personal world, my creativity, my emotions, my sexuality. In our first four games of 2o13, we went 3–1, and I was having runaway success at my position. But when conference play began, we started losing and kept losing. What was the point of working so hard if we couldn’t win when it counted? What was the point of coming so far in my career if my sexuality would make me unwelcome in the NFL? What was the point of being good if it wasn’t good enough?

After five straight losses, a lot of my teammates were talking about transferring or even just quitting. We talked for hours about what our collective problem was, and the conclusions ranged from the coaching staff to the talent level, to the difficult work schedule at Purdue, and everything in between. But I was silently obsessing over my individual problem. I couldn’t live in two worlds and stay sane, so maybe I needed to implode one of them. My personal world, my sexuality, couldn’t change, but the idea of quitting football or not trying to make the NFL felt like a kind of death. I had no choices. I couldn’t run from myself. I was stuck and alone, and I couldn’t even talk to the people I loved about it.

During an evening of playing Madden with Joe in our dorm room, something finally broke open. Joe and I would often play sports video games, but when Purdue football was struggling, our matches got a little more competitive. I felt comfortable with Joe. We had both grown up with financial struggles and estranged fathers, though Joe had navigated his hardships differently. Joe’s upbringing was difficult, as was mine, but where I had focused on my own survival, he was taking care of his two younger sisters and trying to reconnect with his father, inviting him to football games and putting in the effort. I couldn’t even stand texting my father at that point. Both Joe and I had NFL prospects, but he was a bit better at juggling the roles of amazing student, devoted boyfriend, and star linebacker. Though I was gaining recognition, I looked up to Joe. I always did, starting at our 6:oo a.m. workouts together. The few times I could get him to go to a party, I felt proud to hang with him. I was lucky to know him, let alone be close with him.

On the night in question, we randomly selected our teams for the video game. Joe landed on the Atlanta Falcons, me on the New York Jets. Joe liked teams that paired a strong running game with a vertical attack, and he was gashing me with Michael Turner, Julio Jones, and Tony Gonzalez. I was being overpowered—but I wasn’t even trying. Before long Joe realized I wasn’t even putting up a fight. He knew I wasn’t the type to quit. Not virtually, not in real life, never. So even a lackluster Madden effort alerted him that something wasn’t right. He didn’t turn to look at me or put down the controller, but he asked me what was wrong.

I didn’t know what to say. Honestly, a lot of my time in college up to this point had been trying to figure out what I could say. Everyone talked about their problems, but what if the problem was me? But if I couldn’t confide in Joe, I couldn’t confide in anyone. He had picked me up from the bars many drunken nights and never judged me, only delivered me back to our dorm room safe. He was the first to give me credit and the last person to rag on me, but he was always honest. He deserved my honesty back. I was attracted to women, and I knew that with all my soul, but I felt something else.

In that moment, I remembered that Joe and I both loved Frank Ocean more than any other musical artist. When Channel Orange was released, and Frank revealed he was bisexual, Joe had hardly flinched—a piece of knowledge that felt like a sign, or just enough of a push.

Practically shaking, I asked Joe if he felt like we were close as a team, if we jelled well. Joe took a deep breath before answering. “Sometimes. Some people really care, and others don’t give a fuck. They come to practice high and drunk and are just used to losing.”

“How well do you think you know everyone on the team?”

“I know them well enough. I know who is here to win,” he said with a shrug. It was that simple for Joe: he didn’t care about anything other than a man’s character and a teammate’s work ethic.

“What if they were gay?” I asked. The word gay didn’t quite fit me, but at that time, I thought no other description did. As I let the word slip out of my mouth, my video-game quarterback was being sacked. I felt suddenly afraid of what I’d done. I could feel each heartbeat pulsing through my temples. I didn’t look away from the television.

“If he’s here to win and he respects me, I could care less.”

It was an answer that should have made me feel better, but it wasn’t enough.

“What if he was your friend, also?”

Joe took a shaky breath, but I wasn’t sure if it was because he had just thrown an interception to my cornerback or if he was picking up the increasingly blatant subtext.

The Jets were a good matchup for the Falcons, because they had a stout defense. Even as I agonized over my words, I’d managed to focus on Madden a bit. The turnover gave me some momentum, and my guys were suddenly marching down the field.

Joe, eyes still glued to the game, asked me, “How close of friends?”

The world outside of Madden had stopped. My running back had just pushed through a huge hole in Joe’s defense for a touchdown, but I couldn’t hear the simulated announcers shouting. I wasn’t sure how much of what I was saying applied to me. Did it even matter? What if this was just some kind of phase, and my attraction to women won out in the end? What if I married a woman, and this was all for naught? What if the rest of the team found out? What if the truth stained me in some way that everyone in the locker room could see? Would I lose my chance at the NFL and financial security? Would I lose my scholarship? Would I lose my best friend? Why did I have to know what Joe thought about a queer player, what he thought about me?

In a voice barely above a whisper, I answered, “What if it’s your best friend?”

As my question hung in the air, the screen showed the updated score, and Joe went back on offense. On the first play of the drive, he sent Julio Jones up the sideline on a go route. Matt Ryan took his drop step, stepped up, and launched the ball as deep as virtual-humanly possible. True to his real-life version, video-game Julio Jones seemed to climb into thin air to grab the ball, and then dragged my defender briefly before breaking free for a touchdown.

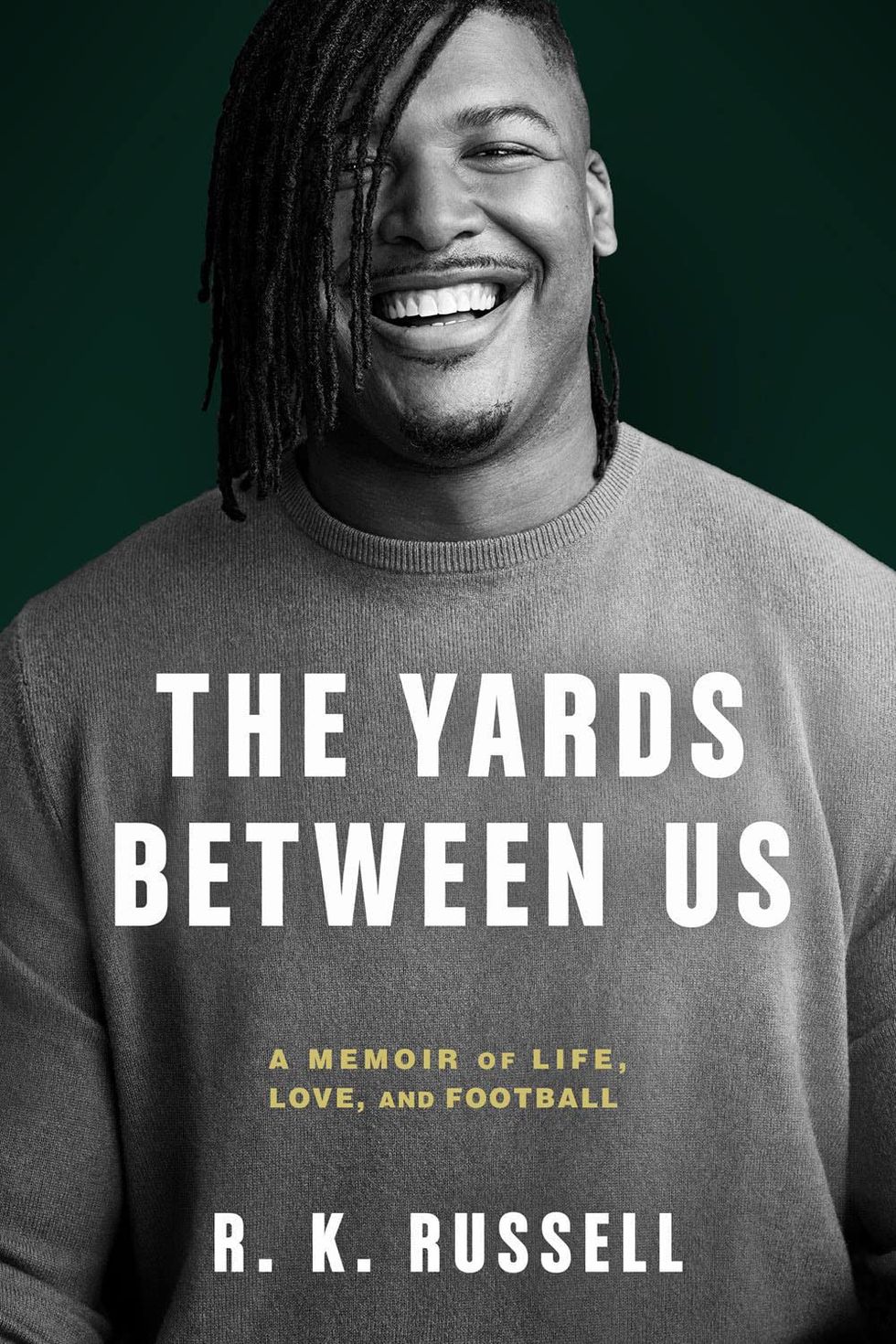

Excerpted from the book The Yards Between Us by R.K. Russell. Copyright © 2023 by R.K. Russell. Reprinted with permission of Andscape Books. All rights reserved.

Contributor

R.K. Russell was a professional football player in the NFL, and is a social justice advocate, published poet, essayist, and artist. A decorated defensive end, he has sacked Hall of Famers and gone up against the fiercest competitors at the height of their game. Since coming out, he has written about his experience as a Black queer man in sports for The New York Times, The Guardian, The Los Angeles Times, Out Magazine, and Queer Majority, among others. Russell has spearheaded multiple NFL Pride initiatives such as the NFL Super Bowl LVI Pride panel and the NFL’s National Coming Out Day PSA. He has been honored by the Human Rights Campaign (HRC) by GAY TIMES (U.K.) as Sportsperson of the Year, and was selected to the prestigious OUT 100 List in 2019. His short documentary, “Finding Free,” was recently nominated for a Sports Emmy and a Webby. He lives in Los Angeles.

Comments are closed.