This story is part of Hip-Hop Is Life, a series of profiles and features that revisit key moments in the intersection of hip-hop and Black men’s health over the last 50 years. Read the rest of the stories here.

BLACK MEN, HISTORICALLY, have shied away from addressing their mental health issues, with merely 26.4% of Latino and Black men experiencing daily feelings of depression and anxiety seeking professional help nationwide. Suicide is now the third leading cause of death among Black youth, and in America, Black men are dying by suicide at a rate four times greater than that of Black women. Hip-hop has consistently documented the necessities of the Black community, but specifying socioeconomic factors which contribute to respective mental health declines was often taboo in rap music.

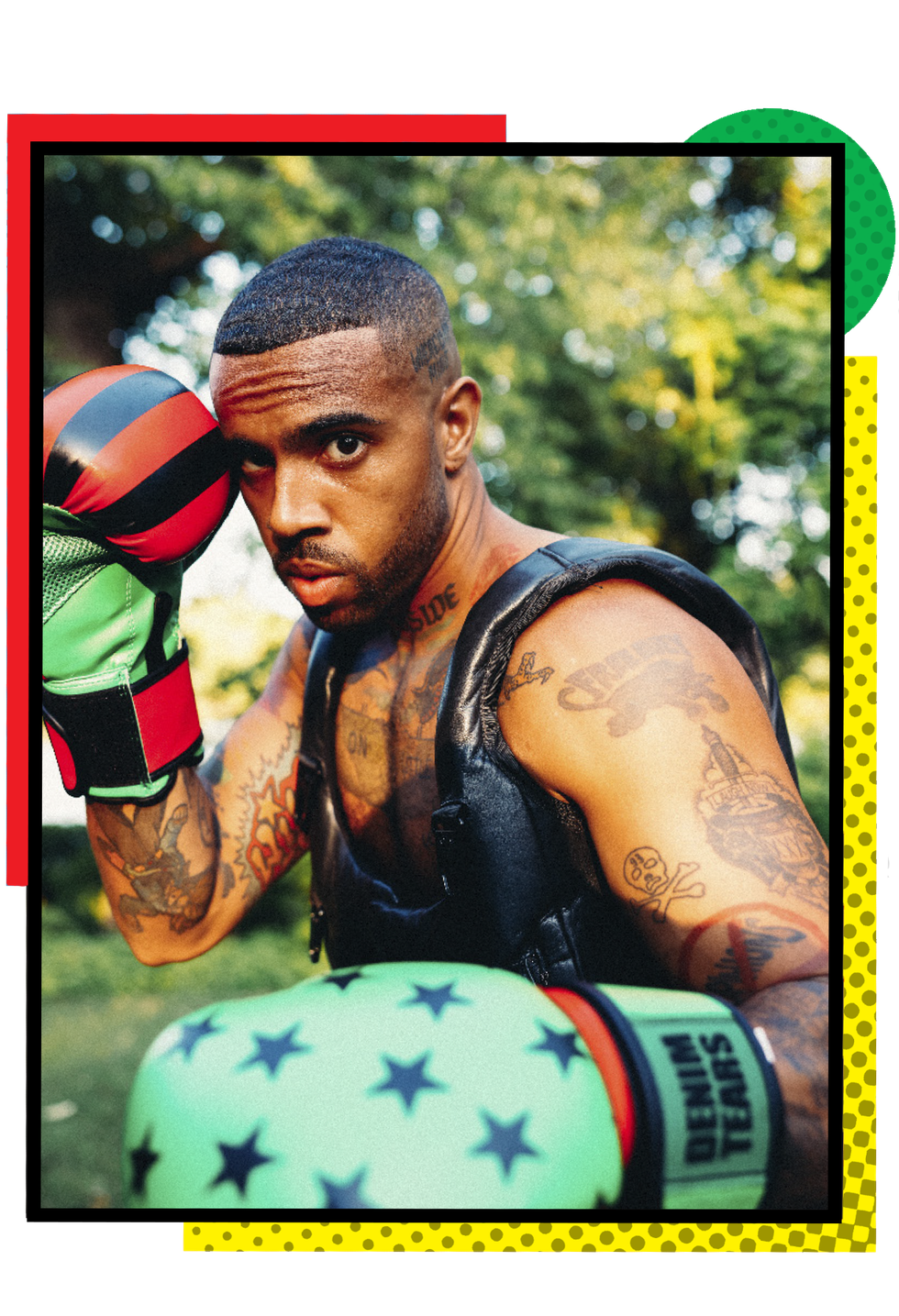

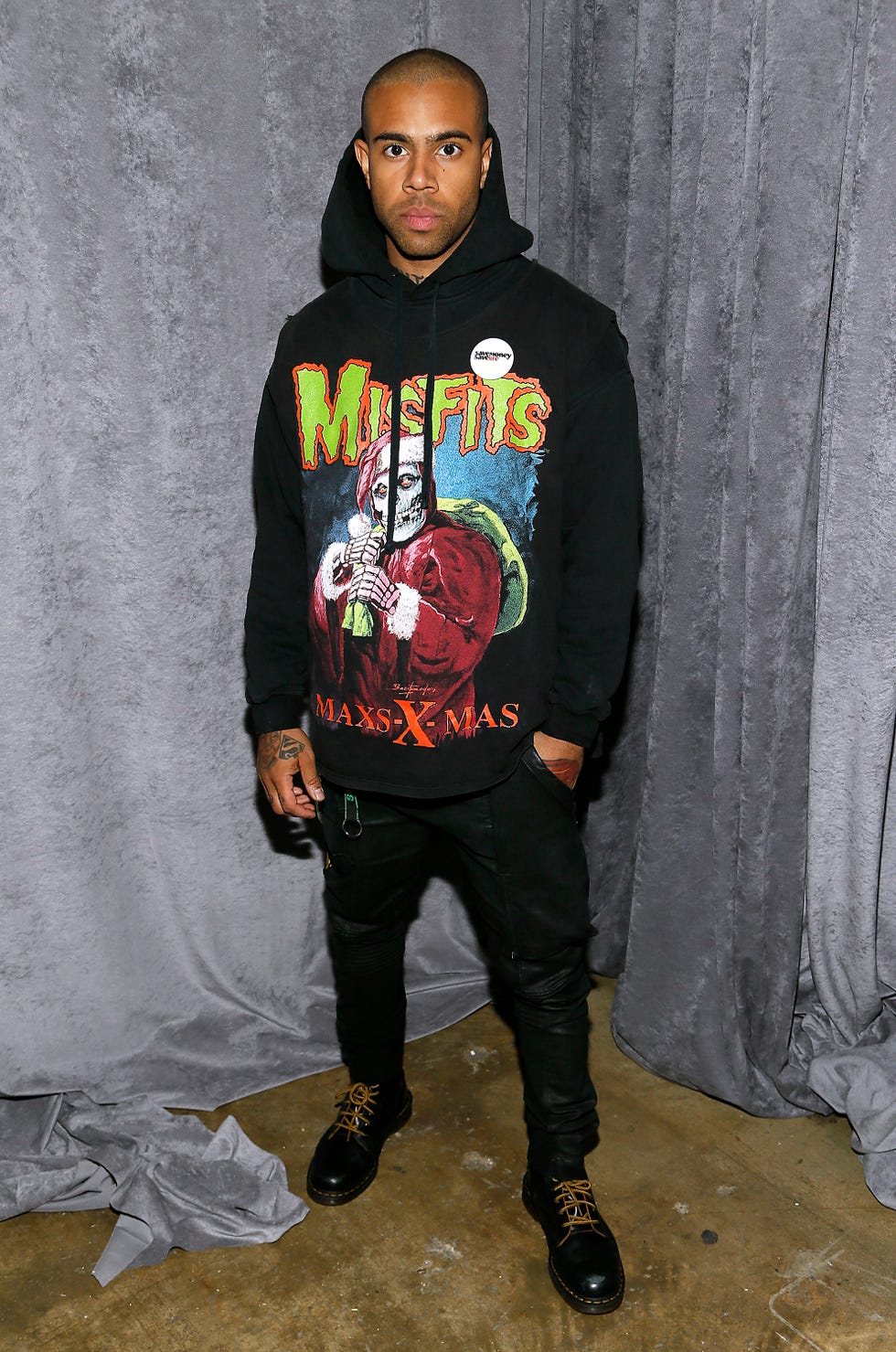

A new generation of hip-hop artists have been working to normalize discussions concerning mental health—none more than Roc Nation rapper Vic Mensa.

“I think hip-hop has greatly shifted toward mental health awareness from the time I have been participating in the public sphere. When I started being transparent about my mental health and struggles… I don’t remember that being commonplace,” he explains while driving through his hometown of Chicago.

The 30-year-old rapper has used his lyrics to talk about past manic episodes (“Medication for depression that I cut cold turkey had the kid manic” from his song “There’s Alot Going On”) and suicidal ideations (“Wishing maybe I’d be better off if I got killed” on his “10K Problems”). When he sends Men’s Health the 16-track rough cut of his forthcoming album, notes of spiritualism play beside the realization that he could have died in numerous instances. For Mensa, transparency isn’t his brand—it’s his duty to his community. “I definitely think my vulnerability through music is my superpower,” he says.

Supporters have also watched Mensa organize from the front lines of diverse causes, such as the promotion of mental health awareness, during his televised interview on The Larry King Show, funding book donations for the incarcerated, building wells in Ghana, educating masses on cannabis’ medicinal benefits, and sleeping on the street during a demonstration to bring awareness to Chicago’s homeless crisis. And although the multi-hyphenate has built a portfolio that has accumulated millions, he remains intuned with the conditions he was born into and the community he serves through separate acts of advocacy and activism.

“A lot of Black men do tell me that they appreciate the transparency and the honesty in my music because those things can sometimes feel out of bounds or off limits for us to talk about,” Mensa says.

Below, the entrepreneurial rapper connects with Men’s Health to celebrate 50 years of hip-hop and dissects how his mental health journey reflects the bigger picture we should all familiarize ourselves with beyond prominent lyrics.

Men’s Health: The opening track on your forthcoming album “Sunday Morning” acknowledges that your journey has reached “incredible heights and indescribable lows.” What are some of those highs and lows? Why has transparency been important to you throughout your career musically?

Vic Mensa: Some of those highs would be performing around the planet and impacting millions of people. I have collaborated alongside the artists I studied and idolized as a child. [I have become] a voice for a lot of people who may not have the space to express themselves. Some of the lows would be the depths of suicidal depression, incarceration, constant controversy, violence, and being a pariah of sorts at times.

Transparency is important to me because it gives me space to see myself and assess my reality in conjunction with my imagination. Nothing on this planet was created or built without imagination. Being transparent enabled me to impact people in a way that I never could have if I acted like it was all good all of the time.

You have documented some of your bouts with suicide ideations musically and through separate interviews. In what ways have these points of dialogue and therapy assisted you in reaching a better place regarding your mental health?

Music is therapeutic for me. It has been a lifelong journey for me to address my mental health. I was suicidal when I was five years old. I am 30. I am so grateful. I feel like I have so much to celebrate because that is not easy.

My mind was predisposed to self-destruction before I even knew what that was. So, to have been able to survive and thrive is an immense blessing. It has been a product of a lot of love. There has definitely been therapy, medication, meditation, plant medicine, mindfulness, mantras, affirmations, books, tears, and smiles.

How do you prioritize joy? What practices do you implement into your lifestyle to promote your wellness?

I have been ruminating a lot about prioritizing joy over fun. I stopped drinking, smoking, and doing drugs. I stopped indulging in women, and all of those things have me prioritizing joy. I love all that shit. You know? But I love myself more. I know that the things that bring me joy are success, creativity, and peace. Many of the things that are fun also rob me of that joy.

Who are some of the first hip-hop artists you remember discussing mental health in their music? How did hearing that help you on your journey?

I definitely think of 2Pac. Geto Boys’ song, “Mind Playin Tricks on Me,” comes to mind. I would also say Kanye West, Joe Budden, and Eminem, but it does not feel like there were so many. Hip-hop has always been a journalistic and introspective art form at its best. But it has also been weighed down by so much machismo and toxic masculinity that there were entire decades and eras when I think artists felt like you had to be so hard to sell records.

Do you feel like your musical vulnerability is a superpower?

I definitely think my vulnerability through music is a superpower. It is also one of the things that express the most magic. I like to think about creativity in terms of magic. When I have the best line or song, it gives me this magic feeling. There is a tingling in my spine.

I also notice that when I have the most clear prayer or connection to a higher power, it can bring the same magical feeling. Sometimes when I pray with that feeling, the things that I pray for will just appear in the most unexpected way. It can only be God.

Your collaboration “Weeping Poets” with Jay Electronica opens with a Minister Farrakhan sample. Can you explain the significance of the 1985 “Power, At Last… Forever” speech’s soundbite for listeners?

Minister Farrakhan, wow! He is really such a prophet on Earth. The things he was talking about in the 80s are still so pertinent to our communities today. He was talking about ownership of our businesses. Minister Farrakhan was talking about the unification of the Black diaspora. He was teaching collective economics. I was studying a lot of the Minister’s speeches when I was making this album.

In what ways will your new album differentiate itself from your past work?

Honestly, it is definitely the first one that really explores faith. I was very agnostic for most of my career. Now, I feel very inspired by faith. I have been studying Islam and studying Christianity. Taking inspiration from that is something that I never did before.

Some fans feel your art assists Black men through issues that may ordinarily go unaddressed. You are known to use your voice. Did you anticipate your spotlight would consistently require this much courage?

I think to survive in this world as a Black person, that requires courage. Also, coming from a very dangerous place, it does feel like the survival of the fittest in a lot of ways. I do not think I ever lacked this courage. I anticipated having to use it, but I don’t think I knew everything that comes along with being in the public eye or being an artist.

Have Black men come to you to tell you your music helped them or reflected their mental health journey?

A lot of Black men do come to me and talk to me about my music as it pertains to their mental health. Honestly, for a lot of human beings, that is one part of the music that transcends racial boundaries. Everybody is going through it in one way or another. Many people are battling mental health disorders and taking medication, and that message of honesty, struggle, and triumph supersedes the boundaries. Yeah, my music is, first and foremost, designed and tailor-made to speak to the experiences of Black people because that is the experience of me.

Our experience with mental health is very unique in the extent of the psychological torture that we have experienced and continue to experience and the amount of stigma that exists around us discussing our mental health. A lot of Black men do tell me that they appreciate the transparency and the honesty in my music because those things can sometimes feel out of bounds or off limits for us to talk about.

Beyond music, you are celebrated for your activism and the diverse ways you uplift your community. How has your mental health journey influenced separate acts of service, including launching the cannabis line 93 Boyz and its literature program ‘Books Before Bars?’

I really view myself as an ideator. I am somebody that creates out of necessity. So, at times, those creations will be a rap or an album that will come. At other times, it will be a community-driven program. All these angles of my personhood and professional experience feed each other.

A lot of the shit I am talking about as I am having a conversation with you are ideas that I have intertwined from reading books by Bell Hooks, Angela Davis, James Baldwin, Malcolm X, and Huey P. Newton. When I started my cannabis company, I figured I needed to be providing freedom if I am dealing with something that has been used to steal freedom from so many people. So, I bought a bunch of books and began to send them to the prisons. I found a way to liberate people mentally.

You founded the first Black-owned and led dispensary in Illinois. What does the ideal future concerning the destigmatization of marijuana look like to you?

We gotta get everybody that is locked up for weed free. You know that definitely has got to be a part of the very near future. Liberation! Expunged the people’s records that have been incarcerated for something that’s now legal. That still hasn’t happened. From a business aspect, it has been expanding the business and operating in more states with my programs.

The Black Star Line Festival and its initiatives brought clean water to separate communities in Ghana. Touching aspects of your upbringing, what level of pride did you feel working alongside Chance the Rapper, a fellow Chicago native—and your father, a Ghana native—to bring these milestones to fruition?

The Black Star Line Festival was a dream come true. I was sitting on a rooftop in South Africa when I thought there must be a way I could bring people together—Black people together. I wanted Black artists around the globe to come to perform for their fans on the continent. We got everywhere else. You can examine the way we vacation to think about what we prioritize. It is not just because of our own decisions.

Our decisions are so often influenced by our conditioning. We are conditioned to believe that it is more aspirational to go to Paris than to go to Africa. And as artists, our touring, habits, and patterns are the same. I thought, “Man! Let me get Chance onboard, and I think I will be one step closer to seeing it come to fruition.” And that is exactly what happened. A lot of people’s lives were changed.

What does Ghana mean to you?

Ghana means home to me. It means family. To be so deeply rooted is an immense privilege that I know I cannot take too lightly. So many of us who have come from colonized peoples have had our connection to our ancestry uprooted. It is a privilege that comes with great opportunity and responsibility.

Concerning your legacy, how do you wish to be remembered?

People talk to me about legacy a lot. I think I can have the tendency to be caught up in the past and the future. I am sure I will start to think about my legacy when I have a child. Right now, I am doing my best to really love the present moment.

A shorter version of this story appeared in the September 2023 issue of Men’s Health.

Bianca Alysse is a Bronx-born author and editor who has written for Revolt TV, Universal Music Group, TIDAL, Sony Music Entertainment, Harper’s BAZAAR, Esquire, Warner Music Group, Billboard, New York Fashion Week, Roc Nation, and SpringHill Company.

Comments are closed.