This story is part of our annual Fit At Any Age series—a guide to the innovations and breakthroughs in aging to help you live a stronger, longer life.

A FRIDAY AFTERNOON in the part of Los Angeles that the maps call Elysian Valley and everyone else calls Frogtown, and here, outside an indoor-outdoor soccer facility on the west bank of the Los Angeles River, sits Wes Bentley, having made it through the better part of one more day.

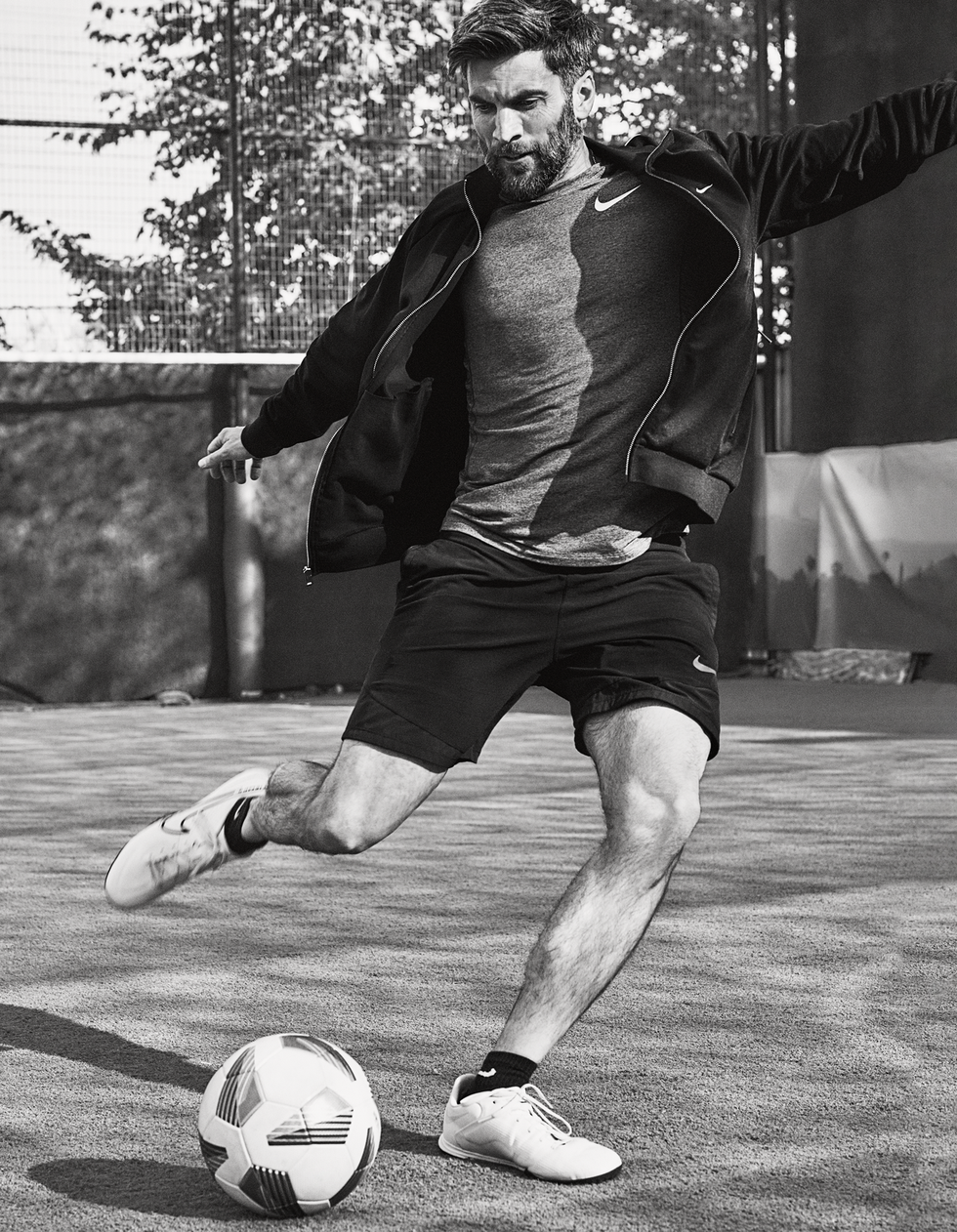

The sun is dipping behind the buildings across the street; the wind’s blowing colder. Bentley has just had his picture taken a hundred times out there on the turf, gamely kicking the ball around for the camera while joking about the speed and agility he’s lost at 44. Now he’s talking about soccer, because of where we are, and because it’s a way into the story of his whole life—from the school team he started as a teenager in Arkansas who’d fallen in love with the sport during the 1994 World Cup, all the way to the private pickup game he fell into about 16 years later, in his 30s, here on the northeast side of L.A., right across the river in Glassell Park. He started out as one of the worst guys on the pitch—a “shitty little field,” he says, where if you slide-tackled on the turf, somebody would warn you to wash up immediately to avoid infection, that kind of city pitch—and spent six or seven years working his way up to playing better and better.

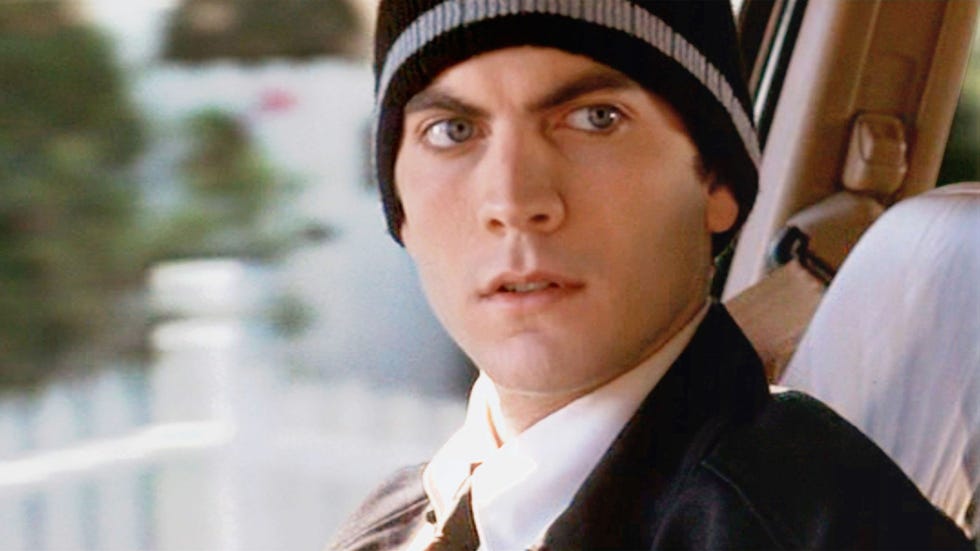

Between those two points—high school and the Glassell Park game—Bentley took up acting, very quickly, and he also very briefly became one of the hottest young actors in the country on the strength of his work in a 1999 movie called American Beauty. He then just as quickly slipped off the radar, into career paralysis, into drug addiction, into the kinds of roles you take when your only priority is paying for drugs, and so went approximately a decade of Bentley’s life.

But today he’s clear-eyed and smiling, a bit of a scruffy beard blunting the intensity of his face, a gold Virgin Mary pendant around his neck, as he talks fast about how he wound up here, with more than a decade of hard-won sobriety under his belt and a juicy part on Yellowstone, a cable-TV show that’s watched by more people than anything except NFL games. He owes all this, he says, to his wife and his two children, and to 12-step programs, but he also owes it to soccer, which gave him something to focus on, a way to make positive use of all the energy and stamina and drive and desire he’d once put into scoring drugs and getting high.

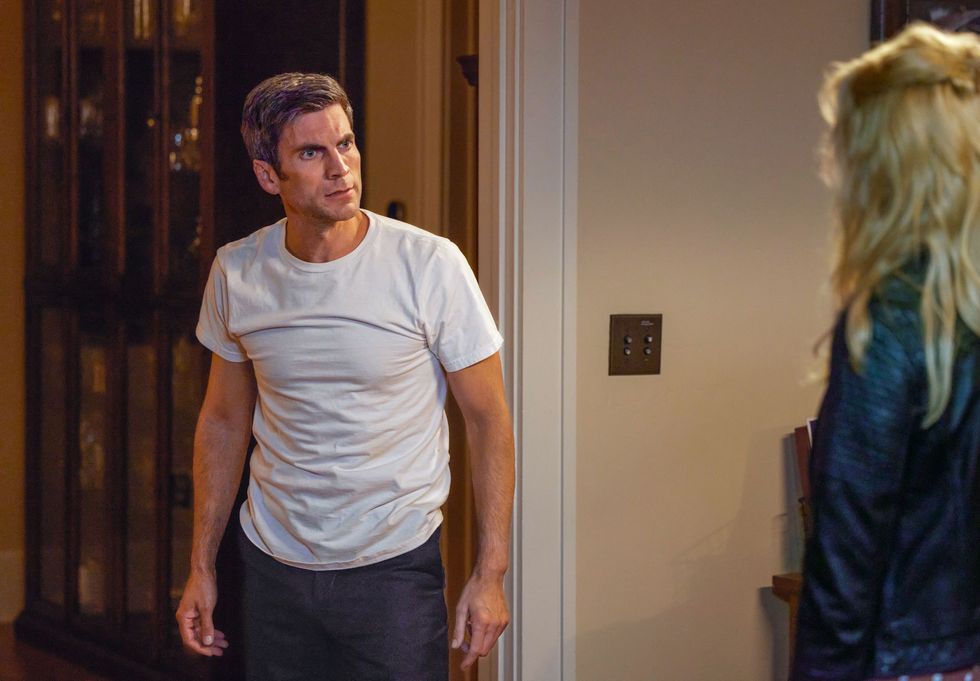

While filming Yellowstone’s first season, Bentley tore his ACL and had to stop playing for a while. But this was a gift, too, because on the Paramount Network series, his character—Jamie Dutton, the Fredo Corleone to Kevin Costner’s cowboy Godfather—lives with an abundance of sadness and has nowhere to put it, and being deprived of his own outlet helped Bentley figure out who Jamie was. “I’d never really explored sadness without a vice,” he says. “In my own life, it would have been drugs, or trying to make people laugh, or being angry. But [to play] Jamie, I had to just be sad.”

He’s spent five seasons in that headspace, living and breathing as a character undone by insecurity, seemingly destined to self-destruct, possibly in a way that also destroys his family. It may not be the role he was born to play, but it’s one that his darkest moments prepared him for. Although Bentley’s personal issues never threatened to bring down a cattle-ranching dynasty, he knows a thing or two about coming apart and striving to pull it together.

THE PARKING LOT is beginning to fill up—soccer moms and dads herding riled-up three- to five-year-olds into the last Lil’ Ballers class of the week. I ask Bentley where he wants to start, and he chooses the beginning, which was Arkansas. Next to John Grisham, he might be the most famous person born in Jonesboro, the state’s fifth-largest city. He and his brothers were “pretty low-income”—his parents, he says, wouldn’t want him to use the word poor. They were both Methodist preachers, so every few years the family moved to a different town, and every time they moved Bentley would reinvent himself, a new personality for each new school.

He was a hyper kid, competitive and quick to anger. For a while, that energy went into sports: basketball and baseball, until he stopped growing and accepted the fact that he couldn’t shoot or hit, and then soccer. Only as those activities faded away did he start to think about performing. He’d grown up watching his parents in church, working the crowd on Sundays. His father sang in the pulpit, and his mother acted out characters from the Bible, especially the women, like Mary and the Samaritan who talks to Jesus at the well. But the Bentley family also loved Monty Python and making each other laugh at home, and that was the first type of acting Bentley did—improv with his brothers, and then acting competitions in school, and then Juilliard, in New York City, where he learned he didn’t know anything, where he stopped trying to get laughs and started trying to actually act.

He dropped out after his first year but doesn’t regret it. He wanted to see what he could do, and he got an answer right away—a casting director spotted him waiting around to audition for Rent, then pulled him out of the line and put him in a movie. That got him an agent, and the agent got him an audition for American Beauty. It was a hot project—Bentley was keen to play teenage pot dealer and abuse survivor Ricky Fitts, but so were countless other actors. “I had seen probably over 70 young actors for that part, many of whom are known stars today,” casting director Debra Zane says. “And when Wes read with me, it was the first time I understood the scene. He came in and, as far as I was concerned, walked out with the part.”

Ricky uses a video camera to mediate his reality, finding visual poetry in drab images—a dead bird, a plastic grocery bag dancing in the wind. The character has an almost Buddhist detachment; Bentley says channeling Ricky’s stillness helped him access a sort of peace he’d never felt before. “I took him and I brought him inside,” he says of the character, “and I wanted to keep him close. And then the whole world had him all of a sudden.”

American Beauty opened in September 1999, became an instant sensation, and ultimately won five Oscars, including Best Picture. But the moment that entered the pop-cultural zeitgeist was one of Bentley’s—that plastic-bag scene, destined to be parodied for years to come, in everything from Not Another Teen Movie to Family Guy. The hype machine went into overdrive on the 21-year-old Bentley’s behalf. Entertainment Weekly praised his “arresting gravitas”; a critic in another publication compared him to Peter Sellers. “My first role!” he says now, laughing. “Whoever that critic was, he bashed everything I did after that—and never claimed responsibility for building me up.”

Within a year, he’d been cast—maybe prophetically—in a biopic of the tragic screen legend Montgomery Clift, which never got made. All this movie-star attention quickly started to feel like expectation, he says, and that started to feel like pressure. The more Hollywood wanted him, the more reticent he became, ducking calls and meetings and interviews. He saw himself as “a ’90s-style independent-film actor” and turned down high-profile roles that didn’t fit those values. “I didn’t want to be a teen heartthrob. I didn’t want to be a sex symbol. I never wanted to be an action star,” he says.

Yet the business was changing. History would remember 1999—the year of American Beauty as well as films like Fight Club, Magnolia, Election, and Being John Malkovich—as a high-water mark for mainstream American cinema, but in retrospect it also seems like the end of an era. The early aughts would belong to franchises like The Lord of the Rings, Fast & Furious, and the Harry Potter movies. None of it felt like Bentley’s scene. He confirms that at some point he was in contention for the part of Peter Parker in Sam Raimi’s Spider-Man and turned the idea down—twice. “I didn’t want to do it, because at the time, comic-book movies weren’t appealing. They were not cool.”

Though he was safeguarding his integrity, he was also squandering a finite moment of opportunity. “The drugs,” he says, “made it okay to do that.”

BENTLEY HAD NEVER partied as a kid, but in Hollywood, he discovered that he loved psychedelics—mushrooms and ketamine, whose potential utility as a mental-health aid he still believes in, at least for other people—and maybe if he’d stopped there, he’d be telling a different story now. “But I ended up going down the cocaine and heroin route,” he says. “Hard drugs. Hard partying. You’re in clubs and you’re at after-parties, and there’s cocaine, and eventually it became heroin.”

That competitive energy he’d once brought to sports came roaring back when drugs entered the picture. “I wanted to be the most impressive drug addict ever,” he says, then looks over his shoulder, suddenly aware that there are little kids around. “Which is sad.” He lost the rest of the decade—disappearing on benders, popping up to knock off another film here and there when he needed the money. He doesn’t want to disparage these movies or the people he made them with, but that was his motivation. “That period was incredibly dark. I did really dangerous stuff. I went downtown. I went and hung with really shady people. I wasn’t trying to kill myself or anything. That was just me: Go far. Be the guy who went the furthest.”

He’d started making electronic music (“It was all really bad once I got sober and listened to it”) and was seriously thinking about becoming a DJ; he was also thinking about becoming a dealer to support his habit. Instead, he took a job shooting a movie that was set in Vegas yet for some cosmically fortuitous reason mostly shot in Saskatchewan, where he could drink but couldn’t score, and while he was up there, he says, “I met a girl, and this girl was awesome and funny and just had the weirdest sense of humor and made me laugh and made me want to live again—like, live live, not go deal drugs.”

Her name was Jacqui Swedberg, and at the time she was working in film production in Saskatchewan. With her help, he finally got sober. (A previous stint in rehab, court mandated after Bentley was arrested in 2008 for passing a counterfeit bill, ended in a relapse.) He and Swedberg married in 2010, a couple years after they met; they now have two children, eight and 12.

He’s gradually rebuilt his life from near zero. “I called it ‘the fire,’ ” he explains. “I lost everything in the fire. I had no car, I had no clothes, I had no money—I was $400,000 in debt.”

Over the years, he says, he’d damaged his reputation, bombing auditions and even showing up to work high. (“Before, I would do it off camera.”) But when he got clean and started working his way back, there were still people who wanted to give him a chance—including Zane, the American Beauty casting director, who helped him get cast as game designer Seneca Crane in the first Hunger Games film. “I remember when I suggested Wes to the director, Gary Ross, he was like, I love that guy,” Zane says. “I don’t think he hesitated even for a second. Whatever Wes had been through, either Gary wasn’t aware or it didn’t matter—it was all about getting the character right.”

After that came supporting roles in Interstellar and Terrence Malick’s Knight of Cups, along with Bentley’s three-season run as a guest star and then a series regular on FX’s American Horror Story, which he says was “a big moment, because that was constant work—I was proving that I would show up and not fall off the wagon.” All this led to Yellowstone. Since 2018, the actor has brought an unnerving, pent-up intensity to the part of Jamie, whose dysfunctional relationship with the rest of the Dutton clan pushes creator Taylor Sheridan’s addictive, soap-operatic modern Western into near-Shakespearean territory. Jamie is the show’s longest-suffering regular, and Bentley laughs when it’s suggested that Sheridan relishes heaping abuse on the character. “I’ve begged him myself. I’ve been like, ‘Taylor, I don’t know if I can do this—I can’t take another beating, man.’ ”

It’s not an easy part to play, but it’s a good one, and Bentley’s never allowed himself to forget how lucky he is to have it. “Taylor had seen American Beauty back in the day and decided back then that he wanted to work with me,” he says. “He somehow believed I was a talent—he was one of those guys who believed in me more than I did. I told myself, if I’m not gonna bring it here, then I don’t have what I thought I had, ’cause Taylor’s bringing it, and I’d better match him.”

SOME OF BENTLEY’S memories from the fire still hurt. In 2008, actor Heath Ledger was found dead of an accidental prescription-drug overdose at his Manhattan apartment. Bentley and Ledger had become friends in 2000—before Brokeback Mountain, before the Joker—while filming The Four Feathers, Bentley’s only real follow-up to American Beauty. They’d formed a close and lasting bond and partied together on occasion. Bentley was high and playing Rock Band when someone told him Ledger had died. “I denied it,” he says. “I was like, Yeah, of course that happened”—and then he kept on pounding the drums for a while, and then he went to score more drugs.

He skipped Ledger’s memorial service. “I tried to go, but I was really messed up, and I felt like that wasn’t right. So I got out of the cab on the way to it. And that sits with me forever.”

Heath would have understood, probably.

“Only Heath,” Bentley agrees. “That guy loved me. Outside of my family, I’ve never felt love from . . .”

He stops. Breaks. In the distance, a coach calls soccer drills: Four. Five. Six. Bentley starts to cry.

“I’d never felt love,” he continues, “from someone like him. And he didn’t care what I was, or what I was like, the stupid things I was doing. He just wanted me to be better. I always thought of him as a brother, and I wish I could’ve given that back.”

He’s okay talking about it, even crying about it in front of people. “I’m an actor. I’m not afraid to feel things. And it doesn’t make me feel worse. It makes me feel better. Because I know I love him and I did love him, but what I’ll take from that relationship is: You’ve gotta show people now that you love them every day. Even when you’re mad at ’em, even when they’re wrong to you”—his voice breaks again—“tell ’em you love them, because it means more than you know, to you and to them. And I didn’t do that well enough with him.”

Bentley lets out something between a sigh and a sob.

“He even begged me to get sober in an email,” he says. “Last email, he was beggin’ me. I didn’t, at first, but later, getting sober, I’d think of that email all the time. One from him and one from my dad, begging me to get sober.”

Even after Bentley got clean, he says, the memory of those dark years left him with a lot of shame to process. “The way I attacked it was by being positive—I’m just gonna go talk about it to everybody and try to help others and heal that shame by doing something.”

But for the past few years, on Yellowstone, he’s played a character who’s not an addict or in recovery but lives from day to day with soul-crushing shame, rooted in his father’s disapproval and exacerbated by his own actions, including a couple murders. While Bentley’s been able to tap into some feelings from his past in mapping Jamie’s depths, there’s a risk and a cost in that.

“My wife has told me, with Jamie, as I’ve gotten deeper, as we got into season 4 and it got really dark, she’s starting to notice,” Bentley says. “She’ll just say, ‘I don’t see Wes—I see Jamie, and I see some real scary sadness.’ So thank God she’s there to help me keep that out of my real life and check [the character] at the door. Which I’ve been very good at, until Jamie. Jamie’s been the hardest.

“I’ve done this show for five years now, and he’s taking up more space,” Bentley adds. “Like, I feel him there all the time now, and I feel him making decisions sometimes. Not now, ’cause I’ve had a few months—but it takes months. I don’t work in the hiatus on this show, not because I don’t want to work; it’s because it takes a long time to shake out of him.”

In a few weeks, he’s heading back to Montana to shoot the second half of Yellowstone’s fifth season, and he knows how it’s going to feel. “It’ll start here”—he points to his lower stomach, some root chakra where Jamie-osity accumulates—“and I’ll feel it just start to fill me with this anxiety and terror.”

It should be no surprise that when the show is over, Bentley says, he’d like to do comedies. “I know nobody thinks of me, and that’s fair. But that’s what I loved first.”

It’s dusk now, and the lights click on over the soccer pitch, illuminating all the Lil’ Ballers running drills on the other side of the fence, including a kid who barely reaches his coach’s waist, serpentining across the grass, driving to the goal, never losing control of the ball—just a boy being naturally great at something, free of worry, free of doubt. Bentley watches his technique approvingly. “Look at that,” he says with a grin. “Every touch, he had it.”

As big as Yellowstone has become, he doesn’t seem worried that Jamie will come to define him. When you’re 21, you might say no to being Spider-Man, for fear of being Spider-Man forever; at 44, it’s easier to see that few things are as permanent as they feel. Bentley says having been through the American Beauty experience—it was a cultural phenomenon, and then it wasn’t—has helped him keep Duttonmania in perspective.

“I know one day there’ll be another show after this, and we’ll be a memory, and that’s great, too,” he says. “So what I’m gonna do this time, and what I have been doing, is I’m gonna enjoy it.”

This story originally appeared in the April 2023 issue of Men’s Health.

Writer

Alex Pappademas has written for the New York Times, The New Yorker, GQ, Grantland, and Men’s Health, among others. He lives in Los Angeles.

Comments are closed.